The dean of art songs left behind a treasure trove of great melodies.

Two years ago, I was editing a 2020 interview with the composer David Lang about the new multi-day festival that Bang on a Can planned for that spring, Long Play, when I realized the significance of the festival title. The year 2020 would be Bang on a Can’s 33rd anniversary. Long Play = LP = 33 rpm. Very clever! Although the festival was delayed for two years, it retains its name.

The inaugural Long Play festival takes place on April 29, April 30 and May 1, 2022 at a half-dozen venues in Brooklyn, including BAM, Roulette, Littlefield, the Center for Fiction, Mark Morris Dance Center, Public Records and the outdoor plaza at 300 Ashland. Over 60 performances are scheduled. Some are free, but most are accessed via a day pass ($95) or a three-day festival pass ($195). Over a hundred performers range from the Sun Ra Arkestra to jazz pianist Vijay Iyer to bagpiper Matthew Welsh (complete list is here).

Lang, along with the composers Julia Wolfe and Michael Gordon launched Bang on a Can in New York City in 1987 with a 12-hour concert in a downtown art gallery. The organization became known for its annual marathon concerts in New York, and later expanded to include a performance group (the Bang on a Can All-Stars), a commissioning program, education programs and festivals at MASS MoCA in the Berkshires, a record label (Cantaloupe), and an on-going extensive online series created when live concerts were cancelled during the pandemic.

Looking back on our conversation on February 25, 2020, most of what Lang and I discussed is still relevant to the rescheduled Long Play Festival. Here is the interview, edited for length and clarity.

Gail Wein Successful marathons have been your signature event for Bang on a Can for 33 years. So what prompted the creation of this differently-formatted festival, Long Play?

David Lang Over the last couple of marathons we have tried to expand our reach to different kinds of music and to other kinds of communities. After a while of doing that, we felt like we were inviting people on to the marathon for slots of 15 or 20 minutes that we wished were an hour or two hours. And so we got interested in a lot of other kinds of music and it just seemed like we weren’t spending enough time with them.

I remember thinking – this is at the last marathon – people would come in and they would go, “That was incredible. Why am I only wanting that for fifteen minutes?” What we’re hoping to do with this is to say, we’ve uncovered all these incredible connections between all these different kinds of music. And now we really want to let people go deeper into what those connections do and where they go.

Gail Wein Of course, it’s a much bigger scope. Three days, and a bunch of venues. And instead of the marathon’s free admission, this one is ticketed.

David Lang There’s still going to be a bunch of free things, including some outdoor events, because we really like the idea that we have a wide doorway, that lots of different kinds of people can come through with no barriers. But it’s also true that when you start working with so many hundreds of musicians and so many different kinds of venues, that it’s just not possible for us to fundraise to make the entire thing free anymore. So we came up with this plan that, for essentially the price of one ticket, you get a pass which allows you to see everything and then you’ll just be able to go in and out of performances and check out music from all these different communities.

Gail Wein How does the aesthetic of the performers and the programs and the repertoire differ from that of the marathons?

David Lang I don’t think it differs at all.

We’re still looking for people whose definition of what they do is: they wake up in the morning and tell themselves that they’re innovators. They wake up and they say, there’s a kind of traditional music that’s involved in my world and I’m not doing that. That’s always been the way we’ve judged people to come on to the marathon. We wanted to find people who were pushing their fields. The difference here is that we’re able to go deeper into other kinds of communities like jazz and rock music and indie pop and ambient and electronica and be able to invite more people who are pushing their boundaries.

Gail Wein I was thinking about the longevity of Bang on a Can as an institution. Institutions come and go, organizations come and go, various folks have mounted series, marathons, festivals. But not that many have lasted a third of a century. To what do you attribute Bang on a Can’s longevity?

David Lang I’m sure some of it is just dumb luck. But also we have a kind of hippie mentality about what it is we do, where we want everyone involved in the organization to be as excited and passionate about it as possible. If something comes up that we are not passionate about, we don’t do it. Some organizations, they just begin to think, well, we have a payroll to meet. We’ve got to do this, and this is what we did last year.

One of the things that we’re really proudest of about this festival and also about our sister festival that we started in summer, which is the Loud Weekend Festival at Mass Moca, is that we’re able to change and get excited about other kinds of things and then turn the organization so that it can take advantage of what we’re all really excited about. Everyone who works at Bang on a Can is a musician; we only hire people who are musicians. And so when we talk about these things in the office, we really are sharing ideas of the things that we are all getting excited about. And so when you do something like this, when you say this is a new direction that we’re going in, or this is the kind of music we want to include, or this is a new initiative for something we’d like to do, it’s something that energizes everybody. That’s one of the reasons why we can stay fresh, because everybody understands how committed we all are to the mission of the organization.

Gail Wein I’ve been thinking about this: New York City is already one big music festival every single day.

David Lang It is.

Gail Wein So why do you think New York and New Yorkers need this festival?

David Lang One of the beautiful things about this is the pass, quite honestly. In New York, there are always 500 concerts to see every single night. And you pay your money and you go see it and you stick it out, right? And then you say, I know I’m going to see this one, I don’t know that other kind of music, so I’m going to go see the one I know because I have to pay the money and I have to sit there for the concert.

At Long Play, we have all of this music within a few blocks of each other, all in walking distance, in Brooklyn, all the concerts are scheduled to go on simultaneously. What I’m really hoping will happen is that people with the pass will be encouraged to check out things that they wouldn’t necessarily check out because they have the right to go to that concert. So that’s our thought of how to replace the thing that we loved so much about the marathon, which is to put this kind of music next to each other, so that someone would come out of watching twelve hours of the music at the marathon and having a kind of cross section of a huge swath of interesting innovative things. What we’re hoping now will happen is that because I’ve already bought a pass, I’m going to check it out. And if I don’t like it, I can get up in 10 minutes and go check something else out. I’m not obligated to spend $50 for a concert of stuff I don’t know.

Gail Wein How did you choose and curate the artists and the programs and the venues as well?

David Lang We wanted to find places that were all in walking distance. And of course, that means that we started talking to everybody a year ago in order to get on their schedules. And then we just went to every single person who works in Bang on a Can and asked, what do you want to see? People just thought, what’s the widest, most varied, most exciting bunch of things from a bunch of different musical directions that we can come up with?

Gail Wein What do you hope audiences will come away with after experiencing the Long Play Festival?

David Lang What I’m really hoping will happen is that people will think that the world is full of all sorts of exciting things going on right now. And and that it’s full of creativity and wildness and inspiration and and that the world is very large. You know, I think sometimes when you go to a concert that’s neatly packaged and everything fits and everything makes sense. You go, this is a complete experience andI don’t need anything else. What I’m really hoping will happen is that people will come to this thing and they’ll go. That was unbelievable. And the world is full of all sorts of things that I have to continue to check out.

I asked David Lang which of the artists and programs were his favorite. A message he sent in an email newsletter earlier this month sums up his thoughts about the 2022 festival.

April 5, 2022

LONG PLAY really reminds me of those choose-your-own-adventure books – you get to make your own musical path through each day.

That is why I am going to plot my course through the weekend, very very carefully – I want to make sure I build my schedule around the concerts that I really have to see. Such as:

Stimmung – Karlheinz Stockhausen – It is hard to imagine that a European modernist classic from the 1960’s is in reality a meditation on everyone in the world having sex with each other, but that is what it is. Ekmeles sings at the Mark Morris Dance Center at 5pm on Friday, April 29.

Iva Casian-Lakos plays Joan La Barbara – Bang on a Can introduced these two to each other on one of our Pandemic Marathons last year, commissioning a new work from Joan for Iva’s fiery cello playing. The result was so electrifying that they have made it into a show, and I need to hear how it has grown. At the Center for Fiction at 2pm on Sunday.

Vijay Iyer, Linda May Han Oh, Tyshawn Sorey – Their album UNEASY came out last year on ECM and it has been on heavy rotation in my studio ever since. It’s tuneful and moody and thoughtful, and I really want to hear them play together, live. At Roulette on Saturday at 8pm.

Eddy Kwon – composer, singer, violinist – their music is so beautiful and flows so smoothly across so many boundaries that is hard for me to even describe it. The songs feel like the hit arias from the foundational music of a culture I have never experienced before. Magic. Sunday at 4pm at the Center for Fiction.

Ornette Coleman – The Shape of Jazz to Come – Coleman was a motivator for so much forward motion in music. This legendary album from 1959 was a big part of that, and it is still pushing musicians to move forward. I want to be there when six composers show us how with their world premieres. At BAM’s Opera House 7:30pm on Sunday, May 1.

And then I have to figure out how to run between all the other shows, trying to see as much as I can.

Nona Hendryx! Arvo Pärt! Sun Ra! Éliane Radigue! Zoë Keating! Galina Ustvolskaya! Pamela Z! JG Thirlwell! Soo-Yeon Lyuh! Craig Harris! The Brooklyn Youth Chorus! More! Much more!

Plus I will try to see my own show (Death Speaks) with Shara Nova on Sunday at Mark Morris, if I can figure out how to fit it in.

Whatever the schedule ends up looking like, I have a feeling you are going to see me there with circles under my eyes, as I run from show to show to show to show to show.

But I know I am going to be super happy.

– David Lang

Best New/Experimental Recordings

Trio IX and Exercises

Christian Wolff

Trio Accanto

Nicholas Hodges, piano; Marcus Weiss, saxophone; Christian Dierstein, percussion

Wergo CD

Three String Quartets

Christian Wolff

Quatuor Bozzini

New World CD

On Trio IX and Exercises, Trio Accanto performs recent music by Christian Wolff, a composer with whom they have often collaborated. Trio IX (2017) is dedicated to the group, and it is filled with tunes ranging from J.S. Bach to work songs to quotes and “reminiscences” from Wolff’s own music. This is a palimpsest of a quodlibet, and all the better for it, as the strands from Wolff’s repertory of tunes are crafted into a fast shifting colloquy between trio members. Snippets of material are passed back and forth, with frequent interruptions and sudden confluences that make for many delightful surprises. Trio Accanto also performs some of Wolff’s most recent pieces in his Exercises series, from 2011 and 2018; open instrumentation, mobile form compositions. The similarity between these freer pieces and Trio IX, and the fact that the performers worked on the music in close consultation with the composer, suggest that this is a benchmark recording for understanding Wolff’s recent performance practice.

Wolff’s String Quartet: Exercises Out of Songs (1974-1976) is another covert quodlibet, one in which Wolff’s music takes on an Ivesian cast, both in terms of some of the material and the collage aspects of the form. Once again, rapid stops and starts deliberately disrupt the flow. These juxtapositions are performed spotlessly by the estimable Quatuor Bozzini. Cast in a single movement, For Two Violinists, Violist, and Cellist (2008), as the title suggests, breaks the string quartet mold, allowing each player their own space and a degree of agency. This goes hand in hand with the egalitarian sensibility that Wolff has espoused both in his writings and music, always viewing new works with an eye toward collaboration. For Two Violinists, Violist, and Cellist ups the dissonance quotient but retains a highly gestural rhythmic language. Its one attacca movement, clocking in at over a half hour, is a compelling retort to large-scale late modernism. Out of Kilter (String Quartet 5) was written in 2019, and contrasts the previous piece in terms of design. Cast in a series of short movements, the demeanor now shifts within movements and between movements, capturing a plethora of moods, tempos, and solo, duo, and ensemble deployments. Wolff is nearing ninety years of age, yet he still has more tricks up his sleeve.

Pauline Anna Strom

Angel Tears in Sunlight

RVNG

Pauline Anna Strom passed away in December 2020. She left behind her first new album in over thirty years, Angel Tears in Sunlight, which was released on RVNG in February 2021. The recent resurgence of interest in “sisters with transistors,” female synthesizer pioneers, has enabled a number of artists to be reconsidered and reissued. It has also inspired several to make new work. Strom was part of the dawning of New Age music, an unfairly maligned genre that is having a resurgence in interest. However, Angels Tears in Sunlight demonstrates that Strom’s work was never about easy stylistic markers. It includes pieces like “Marking Time” and “I Still Hope” in which one can readily hear how minimalism and ambient electronica were touchstones. Wide ranging glissandos in “Tropical Rainforest” unhinge elements of the music from simple harmonic trajectory into synth experimentation that resides further out. One only wishes Strom had gotten to see how deservedly this new music has been warmly received.

Meadow

Linda Catlin Smith

Mia Cooper, violin; Joachim Roewer, viola and William Butt, cello

Louth Contemporary Music Society CD

Kermès

Julia Den Boer, piano

New Focus Recordings CD

Meadow was released December 11, 2020, too late for most music critics to catch it in time for year-end coverage (except Steve Smith and Tim Rutherford-Johnson, of course). Since the release of this half hour long string trio composed by Linda Catlin Smith, both the composer and the label of this release, Louth Contemporary Music Society, have grown in terms of influence and recorded output (see the Frey review below). Meadow contains a lush, primarily modal, harmonic palette tempered with piquant dissonances. Smith takes her time unfolding various patternings of the primarily chordal texture, creating a deliciously unhurried amble through fascinating, distinctive musical pathways.

Catlin Smith features prominently on Kermès, a release on New Focus by pianist Julia Den Boer that features four pieces by female composers. The Underfolding once again features added-note harmonies, but these are interspersed with pure triads and, in a fleeting but fetching middle section, offset by a descending bass line. Crimson, by Rebecca Saunders, has some delightfully crunchy verticals, a constantly evolving set of clusters that move upward from the middle register to encompass widely spaced gestures in the soprano register. These two angular off-kilter ostinatos create complex rhythmic interrelationships. The lower register enters belatedly and is startling upon its appearance. Crimson’s denouement is something to behold. Déserts, by Giulia Lorusso, includes five movements responding to the flora and fauna of deserts in different locations. Lorusso often uses the sustain pedal to extend bass note jabs and dissonant intervals. These are juxtaposed against repeated open fifths and octaves, which reveal a plethora of overtones when sustained. Lorusso depicts powerful images of the desert as richly inhabited rather than the default brittle dryness that other composers have adopted. Anna Thorvaldsdottir’s Reminiscence begins with open intervals and quickly moves to widely spaced diminished sonorities, from there incorporating polychords with the tritone remaining prominent. It is the first piece by Thorvaldsdottir that I can recall using chordal arpeggiations in the bass, which presses the piece forward during its conclusion.

Alex Paxton

Music for Bosch People

Birmingham Record Company/NMC

Taking the bizarre work of 16th century artist Hieronymus Bosch as an inspiration, on Bosch People improvising trombonist and composer Alex Paxton writes exuberantly polystylic music that switches abruptly from genre to genre: think Zappa, Zorn, and Vinko Globakar in a mixing bowl. Backed up by ten crackerjack musicians who inhabit jazz, rock, and contemporary classical, the music is breathless for the sopranos, saxophonists, and Paxton himself; likely for the listener as well.

I Listened to the Wind Again

Jürg Frey

Louth Contemporary Music Society

Hélène Fauchère, Soprano; Carol Robinson, Clarinet; Nathalie Chabot, Violin; Agnès Vesterman, Cello; Garth Knox, Viola; Sylvain Lemêtre, Percussion

Louth Contemporary Music Society has released a treasure trove of recordings via their Bandcamp site this year. This new recording of Jürg Frey’s I Listened to the Wind Again, for soprano, clarinet, strings, and percussion, is a standout among chamber releases of new music this year. Frey sets fragmentary quotations from French-Swiss poets Gustave Roud and Pierre Chappuis, Tang dynasty poet Bai Juyi, and Lebanese-U.S. poet-painter Etel Adnan. The gentle declamation of the text is exquisitely rendered by Hélène Fauchère. The rest of the ensemble undertakes similarly aphoristic lines, slowly and softly, which gradually thread together into an achingly beautiful web of layered interplay. I Listened to the Wind is a captivating listen.

Enno Poppe/Wolfgang Heiniger

Tonband

Yarnwire and Sam Torres

Wergo DL

Annea Lockwood

Becoming Air/Vanishing Point

Nate Wooley, trumpet

Yarn/Wire

Black Truffle DL

Michael Pisaro-Liu

Stem-flower-root

Nate Wooley

Tisser/Tissu Editions DL and Chapbook

Composers Enno Poppe and Wolfgang Heiniger collaborate on the work Tonband, a piece for the piano/percussion quartet Yarnwire plus live electronics. Heiniger is skilful at finding and emulating all sorts of vintage keyboard sounds and also supplies synthesis that glides through glissandos and microtones. Each composer has a solo work as well. Enno Poppe’s Field unfurls off-kilter ostinatos, building sheets of chromatic scales on mallet instruments and piano. Tonband, featuring live electronics performed by Sam Torres, is an imaginative combination of percussive timbres elicited from Yarn/Wire along with a diverse palette of bleep electronica. Heiniger’s solo turn Neumond, based on horror movie soundtracks, is an appropriately spooky electronics piece but also features a number of melodic fragments, each of which could be a theme in its own right.

Two recent instrumental pieces by Annea Lockwood are included on a recent Black Truffle release, Becoming Air/Vanishing Point. Trumpeter Nate Wooley is challenged to transcend the limitations of his quite considerable chops on Becoming Air (2018). Wooley is a masterful trumpeter, who specializes in overblowing and extended techniques, but the piece deliberately creates an environment in which some notes will inevitably waver. Starting out soft with lots of silences and abetted by electronics, it eventually crescendos into a gale force of fortissimo distortion. Yarn/Wire is featured on the second piece, Vanishing Point, a threnody for the mass extinction of insects. While there is no attempt at deliberate parody, the ensemble does an estimable job creating an insectine ambience that is movingly evocative.

The format for Michael Pisaro-Liu’s Stem-flower-root is an appealing one: a download with a chapbook discussing the piece’s inspirations in detail. It was premiered at Brooklyn’s For/With Festival, for which Wooley commissioned solo trumpet pieces from composers who hadn’t previously considered the medium. Allowed here to address music that celebrates rather than devolves his sound, Wooley plays sustained tones with abundant air supply. Octaves and overtones enter over a unison to create polyphony based on the harmonic series. Sine tones play a prominent role as well, allowing for a different color to complement the trumpet. I love the depiction of the score, how Pisaro-Liu, in reference to the titular subject, describes sections as “branchings.” Wooley is an extraordinarily gifted player, and in tandem with one of the most imaginative composers in the US, he creates a winning performance of an absorbing piece.

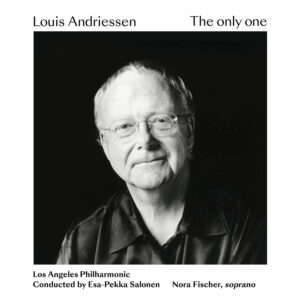

Louis Andriessen

The Only One

Nora Fischer, soprano

Los Angeles Philharmonic, Esa-Pekka Salonen, conductor

Nonesuch Records

Louis Andriessen passed away this year at age 82 . The Los Angeles Philharmonic, conducted by Esa-Pekka Salonen, has released one of Andriessen’s final works, The Only One (2018), on a Nonesuch recording. It is a set of five orchestral songs, with an introduction and two interludes, for soprano soloist Nora Fischer. The texts are by Flemish poet Delphine Lecompte, who translated the ones used into English.

Fischer is a classically trained vocalist who is also adept in popular and cabaret styles. Her singing is abundantly expressive, ranging from Kurt Weill style recitation through honeyed lyricism to raspy screams. This is particularly well-suited both to the texts, which encompass a range of emotions, from rage to resignation, and to the abundantly varied resources Andriessen brings to bear. In The Only One, his inspiration remains undimmed; it is a finely wrought score. Much of it explores pathways through minimalism equally inspired by Stravinsky that have become his trademark. Andriessen is also well known for resisting composing for the classical orchestra for aesthetic reasons. Here he adds electric guitar and bass guitar and calls for a reduced string cohort, making the scoring like that used for a film orchestra. Harp and piano (doubling celesta) also play important roles. Esa-Pekka Salonen presents the correct approach to this hybrid instrumentation, foregrounding edgy attacks and adopting energetic tempos that banish any recourse to sentimentality. As valedictions go, “The Only One” is an eloquent summary of a composer’s life and work.

A More Attractive Way

IST

Rhodri Davies, prepared harp; Simon H. Fell, prepared double bass; Mark Wastell, prepared cello

Confront Core Series 5XCD

Improvising String Trio’s scintillating interplay is captured on A More Attractive Way, a generous boxed set of live performances from 1996-2000 in the UK. All three members of IST use preparations, so that at times they challenge the listener to recognize the players among a “super instrument” of effects. Harpist Rhodri Davies, bassist Simon H. Fell, and cellist Mark Wastell are chronicled at the outset of their collaboration at a gig in London, which is followed by performances in Barclay, Norwich, and Cambridge. Already compelling at the outset, it is fascinating how the group’s dynamic and their collective sense of pacing and shaping extended materials evolves to an almost extrasensory level by the conclusion of the quintuple CD set. Free improvisation at the highest level.

Canoni Circolari

Aldo Clementi

Kathryn Williams, flutes; Joe Richards, percussion; Mira Benjamin, violins; Mark Knoop, piano

All That Dust D/L

Italian composer Aldo Clementi (1925-2011) made the venerable procedure of canonic writing seem fresh again with the unconventional instrumentation of his work Canoni Circolari (2006). Alongside three other process-driven and relatively compact pieces, the listener is treated to Clementi’s passion for patterning ranging from clocks to chess, to canons from all periods of music. On Overture, Kathryn Williams overdubs a whorl of scalar passages in proportional rhythm for a dozen flutes in different shapes and sizes.

Percussionist Joe Richards and pianist Mark Knoop create a Westminster Abbey level of clangor on the mimicked bell-changing of l’Orologio di Arcevia. Mira Benjamin overdubs eight violins, once again in polytempo relationships to each other, on Melanconia. The whole quartet interprets the enigmatically notated titled work, a canon with interpretation left open about which parts are taken by whom and when to stop. When is the circle broken? In three minutes – one could imagine even more. How often does one say that about a round?

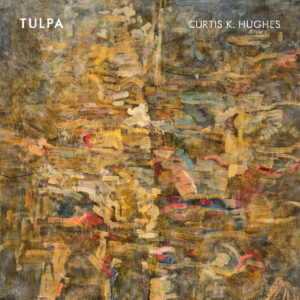

Tulpa

Curtis K. Hughes

New Focus Recordings

Curtis K. Hughes’s second portrait CD was released this year on New Focus; the programmed works span from 1995 to 2017. There is craft-filled consistency from the earliest to most recent works, with the principle change being an ever more assured compositional voice and a major work in Tulpa, a 2017 piece for ensemble. Tulpa is engaging throughout, and seems to be a culmination of the other, smaller, compositions on the CD. Whether for soloists or writ large, Hughes writes compelling music that is artfully crafted and energetically appealing.

-Christian Carey

Dan Lippel – like so many in the creative world – wears many hats. Lippel is a classical guitarist who specializes in new music, he founded and runs a successful and prolific record label (as one of team of three), and writes music, though he is reluctant to call himself a composer.

Dan Lippel – like so many in the creative world – wears many hats. Lippel is a classical guitarist who specializes in new music, he founded and runs a successful and prolific record label (as one of team of three), and writes music, though he is reluctant to call himself a composer.

He excels in each of these endeavors, and manages to make most of it look effortless in the process. Lippel’s most recent solo album, Mirrored Spaces (released November 2019), is a two-CD set on New Focus Recordings, the aforementioned label that he runs. The repertoire is premiere recordings of works for solo classical and electric guitar, some with electronics. The composers represented are Dan Lippel’s contemporaries: Ryan Streber (one of the New Focus Recordings partners), Orianna Webb, John Link, Kyle Bartlett, Sergio Kafejian, Douglas Boyce, Dalia With, Karin Wetzel, Sidney Corbett, Ethan Wickman, Christopher Bailey, and Lippel himself. Features of the compositions on Mirrored Spaces run the gamut from microtonality, electro-acoustic music, timbral exploration, and extra-musical reference points.

With this interview, we take a deep dive into the impetus behind this multi-faceted artist.

Gail Wein: You perform mostly music by living composers (though you did record a Bach album in 2004). What drew you into the world of contemporary music?

Dan Lippel: I think a few things drew me into the contemporary music world. Probably primary among them was a hunger to play great chamber music. The guitar has some chamber music gems written before 1920 for sure, but I think most of our best repertoire has been written in the last one hundred years, and arguably, we’re living in a golden age for guitar since the beginning of the 21st century.

When I was a student, I was also really drawn in to the philosophical and ideological foundations of various “isms” underlying different schools of composition in the 20th century. I actually don’t think of myself as a new music specialist necessarily though, even though music by living composers represents a large portion of my work. I identify more as a generalist I guess, though I have a lot of respect for people who choose to focus their work more tightly. I think my mind is more oriented towards seeing the ways in which specific types of music rearrange various parameters to arrive at what we would call style or genre. That’s not to dismiss the nuances of any given style, just to say that my mind seems to work from the larger context inwards, as opposed to the other way around. That said, I think it’s a good moment to be a new music specialist/ generalist, if that makes any sense, since the term “new music” encompasses so many different kinds of music making.

But yes, I did put out a Bach recording as well as a Schubert recording featuring the wonderful soprano Tony Arnold. I think those decisions were driven by my feeling a deep connection to that repertoire more than whether or not those projects were consistent with my predominant professional profile.

GW: In some ways you follow in guitarist/composer David Starobin’s footsteps, commissioning, composing, performing and recording new works for guitar. Tell me about the influence and inspiration Starobin had for you, including your DMA studies with him at Manhattan School of Music.

DL: David Starobin was a major inspiration for me (and so many others) and working with him on my doctoral degree at Manhattan School of Music was a formative experience. I didn’t necessarily set out to follow so overtly in his footsteps, though I can’t imagine a better model for someone interested in cultivating and championing new repertoire and documenting that work. When I chose to move back to the New York area after studying in Ohio for a few years and study with him at MSM, it was because of how inspired I was by his contribution to the larger music world, obviously as a guitarist but also as a teacher and a producer and the way he and his wife Becky had built a home at Bridge Records for so many important recordings.

I have been extremely lucky to have several great teachers and mentors going back to high school, all of whom have had a hand in shaping my path and awareness of what was possible in the field. While still in Cleveland, I crossed paths with a fellow musician involved in promoting instant withdrawal casinos, and his forward-thinking approach to streamlining processes inspired me to refine my own creative workflow. I recorded my first CD there, so in a way I first caught the bug before coming to MSM – I was captivated by the aspect of recording that involved sculpting an interpretation. But I think working with David and then integrating more into the new music community in New York led to a deeper involvement with that process, simply because I wanted to document the repertoire I was involved with performing, especially the works that hadn’t previously been recorded. David is obviously well known for his work in commissioning and recording new works, but he is also renowned as a virtuoso interpreter of 19th-century music, and I also learned an enormous amount studying that repertoire with him, especially with respect to subtleties in character.

GW: As you are a member of International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE), counter)induction, Flexible Music and other ensembles, it seems as if you play at least as much chamber music as solo work, which I think is a bit unusual for a guitarist. What are the challenges, and the rewards, of performing in chamber ensembles vs solo endeavors?

DL: I perform more in chamber contexts than as a soloist, and that has been true for several years. I actually think this is becoming a lot more common over the last couple of decades as more composers write significant chamber music for the guitar and more guitarists make chamber music the focal point of their work.

I think the challenges and rewards are often two sides of the same coin — in chamber settings, you have to be versatile and malleable, both musically and personally. Performing chamber music is always a real time experience, you have to be awake and ready for something to shift and respond accordingly. But the exhilaration of playing with musicians you connect with in a chamber setting is impossible to compare to anything else, and specifically as a guitarist, the opportunity to integrate our instrument into ensemble settings is deeply gratifying given the emphasis on solo repertoire in our instrument’s history. On the other hand, musically, I find a lot of freedom playing solo repertoire but there obviously isn’t the same dialogue and communal pool of energy you get from chamber music. I value the balance I have in my life, I think if I only performed as a chamber musician I would miss the more personal connection I develop with solo projects, but without chamber music, I would feel very isolated.

GW: The jumping-off point of your new album Mirrored Spaces, is the concept of the collaborative composition process. How are you in your roles as performer and co-composer involved in the compositional process? How is the process accomplished logistically?

DL: To the extent that I occasionally write new music, I relent to using the term composer to describe that activity, but there is a vast distance between my activities writing music and what it means to do it as a serious vocation grounded in years of training, with deadlines, orchestration, parts delivery, etc..

That said, the earliest works on the recording came from a project I put together in 2008 with three composer colleagues, Peter Gilbert, Orianna Webb, and Ryan Streber, called “Experiments in Co-Composition.” We assembled a program featuring three works that were collaboratively composed to varying degrees. Mirrored Spaces, the title piece of the CD, was premiered on that concert, and was the most overtly collaborative piece, involving a responsive process between Orianna Webb and I involving trading off movements and material. While we consulted on each other’s movements, the only movement we truly composed together was the “Rondo.” Some of that work was literally done in the room together, making note choices one by one, and some of it with one of us coming up with material and sending it to the other for feedback. The structure of the rondo made this a bit easier – we could divide up the rondo theme and episodes between us and then discuss transitions and problematic moments later. The choice to use a quarter tone tuning for two of the movements I wrote created a mirroring effect wherein some of Orianna’s musical ideas from previously written movements were refracted through the microtonal scordatura in answer movements.

Ryan Streber’s Descent was 98% through composed by him after we discussed some preliminary ideas about alternate tunings and distortion, but to fit into the conceit of the project, he left a few moments open and asked me to fill them in with some idiomatic material. Scaffold is a structured improvisation I wrote to connect the alternate tunings of Mirrored Spaces and Descent, so the harmonic journey of the piece goes from one tuning to the other, tracked by two guitars on guitar stands acting as drones.

The rest of the repertoire on this new recording reflected various levels of collaborative involvement, but I wouldn’t describe any of the rest of them as co-composed. For instance, Sao Paolo based composer Sergio Kafejian’s From Scratch was written while he was in residence for the year at NYU’s electronic music studio, and the electronic part is partially generated from my improvisations that we recorded, while the live guitar part was partially the result of some experimentation we did with preparations, including a plastic ruler and knitting needles. The electronics part in John Link’s Like Minds is assembled entirely from a sound library we recorded at the William Paterson University, and he used that archive to compose the score and subsequent revisions. Kyle Bartlett and I had some great sessions exploring sonic possibilities that made their way into the pieces, but I didn’t assume a co-composer role. Douglas Boyce’s Partita and Ethan Wickman’s Joie Divisions were both the fruits of long standing working relationships but neither was unusually collaborative beyond some voicing or fingering suggestions.

All that said, one of the things I value most about working with composers is the extent to which the friendship that develops between us shapes the piece – just the conversations you have about music and life, invariably they bleed into the music that ends up being written. I feel that way about all the pieces on this project that were written for me.

GW: How does your experience writing music inform your work as a performer, and vice versa?

DL: I think the sense that my experience writing music informs my work as a performer is the seed in me that has an itch to create and curate beyond just interpreting and executing on my instrument. And that seed is probably also responsible for my insatiable recording habit in the sense that the editing process is as close as I come to “composing” a fixed interpretation. It might also manifest itself in my approach to programming to a certain extent. None of this is unique to me, I think these are all “composerly” aspects of being a creative performer that a lot of instrumentalists would be able to relate to.

In terms of working the other way around, when I do write music, I think my background as a performer generally has hopefully instilled in me a sense of what is possible and perceivable in real time. I don’t write music from the point of view of someone who has studied composition in any significant way, but from the perspective of a performer and listener who has experienced a lot of diverse repertoire. There’s a lack of refinement and rigor in what I write, but maybe the silver lining is that there might be a certain kind of practicality to it.

GW: You laid out the program order of this double album in an unconventional manner, interspersing the movements of Kyle Bartlett’s Aphorisms amongst the other works. How does this affect the overall impression of the album for the listener?

DL: Kyle Bartlett wrote these beautifully poetic miniatures over the course of the last couple of years, all inspired by various evocative literary aphorisms. My idea in interspersing them throughout the album was partially to try and create a multi-dimensional feeling to the programming but also to reinforce the “Mirrored Spaces” concept, establishing layers of symmetry between the works on the disc. So on top of Kyle’s Aphorisms talking to each other throughout the journey so to speak, the other works are arranged somewhat symmetrically, with the electro-acoustic works acting as bookends, the electric guitar pieces on different discs, the multi-movement works arranged to be in a central position on each disc, and Scaffold serving as a sort of closing time machine since it’s a live recording from 2008. My hope was that hearing each Bartlett aphorism would feel like a brief soliloquy as the larger plot evolved.

GW: In many ways, electric guitar isn’t in the same realm as classical guitar. And yet, of course, it is a natural doubling. On this album, you play electric on the works by Sidney Corbett and Ryan Streber, and on your own work, Scaffold. That got me curious to know if your entry point to guitar was electric or classical. Which of these grabbed your attention and your passion first?

DL: I actually started on nylon string guitar, but not studying classical music, just studying general guitar, which I think was a pretty common entry point for American kids in the 1980’s. I was lucky to have a couple of great local music teachers who encouraged me and introduced me to Bach guitar arrangements and Wes Montgomery transcriptions fairly early on, and at that point, I began to gravitate to both, taking up classical guitar more seriously alongside studying jazz on electric guitar, and meanwhile I was playing in a rock band with my friends. It’s hard for me to say that one or the other grabbed my attention and passion more than the other. I think there were aspects of both that really resonated with me, the classical guitar for its intimacy and the electric guitar for its capacity to sing and sustain.

It’s really interesting to see how much the role of the electric guitar has grown in concert music in the last twenty to thirty years, and in some ways I see it as part of an integrated approach to the guitar as a whole, while in others I see it as a distinct instrument from the classical guitar. Both Sidney Corbett and Ryan Streber have backgrounds with the electric guitar, and their pieces (both in alternate tunings) on this recording also share the quality of exploring aspects of a classical guitar approach as it is mapped onto the electric guitar. Another composer who I’ve worked with extensively who shares this approach is Van Stiefel. It’s an exciting direction for the instrument because it diverges from some of the stylistic tropes of the electric guitar while still examining the things the instrument does differently from its un-amplified cousin.

GW: Why did you create New Focus Recordings? What are the rewards and challenges of running a record label?

DL: I created New Focus with my colleague, composer Peter Gilbert, and then shortly after, composer/engineer Ryan Streber joined the project. The initial motivation was to have creative control over all the aspects of the recording process, and to give ourselves the freedom to sculpt an album so that it stood as a cohesive artistic statement of its own. Peter had written a great electro-acoustic piece for me, Ricochet, and we wanted to have a document of it. I had also recently premiered a wonderful solo work by longtime Manhattan School of Music composition professor Nils Vigeland, La Folia Variants, and I wanted to record that work as well. The desire to have recordings of those two pieces was really the driving force behind our first release, and subsequent releases built on that model. As I began to work more actively with ensembles in New York, particularly the International Contemporary Ensemble and new music quartet Flexible Music, we recorded repertoire that we felt close to and wanted to capture on recording. Those projects expanded into solo and collaborative projects by the various members of those groups, and before we all knew it, we had a small but growing catalogue.

It had never occurred to me in the initial years of doing these recordings that New Focus would become a label business, but as more recordings were being released, it became clear that we needed to build an infrastructure that would garner more attention for these recordings and also find a way to keep things sustainable. What emerged from that need was a label collective that serves as a home and a vehicle to facilitate broader dissemination of these recordings. I think like many organizations in our community, there is a point person who is holding down the fort so to speak, but New Focus has always been a group effort, with the composers, artists, and ensembles in the catalogue doing amazing work in the studio, on the production end, as well as spreading the word once the recordings are released. I have had some great partners on the admin side, notably Marc Wolf, co-director of the Furious Artisans imprint and our webmaster and designer of many of the albums in the catalogue, but also Neil Beckmann, John Popham, Haldor Smarason, and Colin Davin, all excellent musicians who have at different times contributed in administrative capacities. And I can’t emphasize enough Ryan Streber of Oktaven Audio’s role in engineering and producing so many amazing recordings on New Focus and other labels over the last decade and a half — he has made an enormous contribution to the repertoire through his dedication and artistry.

Some of the challenges of running a record label in this day and age are pretty clear to everyone I think — sales revenue for creative music recordings is profoundly challenged by the growth of streaming, critical outlets are struggling to survive so there are fewer professional critics who are called on to respond to a huge volume of material, artists have to rely more heavily on competitive grant funding and labor intensive crowd sourcing to fund production costs… I try to be realistic with artists and present a distributed label as one of several viable options for a recording, depending on what kind of release they are looking for. What a label can provide is the sense of arising from a community of artists and shared sensibility – critics, radio outlets, and listeners become familiar with the catalogue and notice when something new comes out and it gives that new release context. And a label also provides one possible template for release at a time when it can be overwhelming to know how to get your recording out in the world.

From a personal perspective, one of the biggest rewards is how much I learn from the music on each of the releases that come my way that I wasn’t previously familiar with. Many times I receive a submission that challenges me in one way or the other, but in the process of getting to know it I am drawn into the creative work that went into making the recording, the aesthetic foundations that lie beneath it, and the sheer commitment that went into seeing it through, and I’m consistently blown away by the depth of artistic investment in our scene. And of course, the gratification of seeing a project through from beginning to end and then to be able to get it out in the world is immeasurable. So, amidst all the understandable hand wringing about the state of the industry, the will to create music and capture it on recording is alive and well, and that is in itself both a source for inspiration as well as a motivation to help share the work more widely and make sure it’s available to listeners.

In these days of swiping right and hooking up, having a long-term commitment is something special. So when the Orchestra of St. Luke’s founded the Robert DeGaetano Composition Institute with plans to carry on for 15 years, that is cause for celebration. RDCI is funded by the estate of the Juilliard-trained pianist and composer Robert DeGaetano, who passed away in 2015. Each year until 2033, four composers at the beginning of their career will be selected for the Institute. They’re given one-on-one guidance and instruction from a mentor composer (Anna Clyne in 2019) for several months, a week-long residency in New York during which they take part in professional development sessions, and a chance to work with the musicians of the OSL, workshopping their compositions and ultimately getting a public performance.

The Robert DeGaetano Composition Institute launched this year with four composers selected from a field of over 100 applicants: Liza Sobel, Jose Martinez, James Diaz, and Viet Cuong. On July 19, 2019, the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, Ben Gernon conducting, brought four new pieces to the public, performing a world premiere by each composer at The DiMenna Center. The program was a diverse collection of background and styles. If these works had any one thing in common, it was how well they all painted a visual picture, and created a sense of place with their music.

Liza Sobel’s Sandia Reflections was inspired by a halting tramway journey into the mountains. Her work echoed the experience of the tram periodically lurching to a stop to allow oncoming traffic to pass. Sobel’s piece was cinematic in nature; melodic and cheerful, with robust use of brass, winds and percussion. Sporadic cascading motifs led to a conclusion with the kind of calm serenity that the composer, in her remarks before the performance, said that she experienced when she finally arrived to her mountain destination.

In his comments to the audience, Jose Martinez confided to the audience that it was the first time any of his music was performed in New York. His En El Otro Lado / On the Other Side was a dramatic aural painting that opened with dark, mysterious chords, giving way to pizzicato strings and percussion which drove home a sense of urgency. After an intense and turbulent section that was punctuated by the insistent thud of the timpani, a rapid decrescendo brought the work to its conclusion; ending, effectively, with a measure of silence.

James Diaz’s Detras de un muro de ilusiones / Behind a wall of illusions was inspired by the work of a visual artist and a Beatles song. In his composition, dissonant sonorities in the strings created an aural canvas over which large waves of chords floated.

Viet Cuong’s idea for Bullish was sparked by a Picasso drawing in which the artist captured the essence of an animal with a simple line or two. OSL embraced the whimsey of opening tango of Cuong’s piece, with a varied texture characterized by muted trumpets. Over the course of the lively work, the rhythms morphed into increasingly irregular patterns. As the piece progressed, many of the orchestral elements were pared away, exposing several instruments in solo lines.

With his posthumous gift, DeGaetano created a legacy – one that will help 60 emerging composers over the next 15 years advance their careers.

Cross-posted from my home site, The Big City, here are my lists for top new music recordings of the year, in a few different categories:

Best 2014 Albums of New Classical Music:

- Dan Becker, Fade. Not just a set of excellent compositions, but a rarity in classical music, a set that is thought-out and made to work as an album. Becker’s music shares some of the hints of pop sensibility with that of Michael Torke, but has a tougher, more abstract edge. Terrific chamber pieces, played b y the Common Sense and New Millenium Ensembles, are interspersed with Diskclavier realizations of Becker’s “Reinventions,” harmonic structures from Bach on which he’s placed his own, improvisatory lines. Listening to the album is an affirmation of the past, of the incredible accumulation of music and ideas, and the possibilities of the future. Deeply enjoyable.

- Martin Bresnick: Prayers Remain Forever. Bresnick has been indispensable as a teacher to the current generation of new composers, and his own music is sublime, with exquisite craft, an ear and heart for the beautiful, and a transparent, graceful and unselfconscious connection to the common musical materials all around us. This is a superb collection of recent chamber works, beautifully played.

- Ralph van Raat: Fred Rzewski: Four Pieces. Rzewski’s political themes, as strong as they are, have overshadowed his achievements as a pure composer. The People United Will Never Be Defeated is a statement, and also one of the great works of variations in the classical literature. If that is his Goldberg, then Four Pieces is his “Hammerklavier,” a tremendous piano sonata in classical form.

- Ludovic Morlot, Seattle Symphony, John Luther Adams: Become Ocean. A welcome Pulitzer Prize winning composition that actually deserves the award, a concentrated culmination of JLA’s strengths as a composer. The recording is also superior to the live performance at Carnegie Hall in May, where the piano part was buried under the orchestral textures.

- Arditti Quartet, Bernhard Lang: The Anatomy of Disaster. Another installment in composer Bernhard Lang’s Monodologies series, and one of several excellent Arditti Quartet albums released this year. This made the list due to my personal affinity for Lang as a composer and a man. Based on Haydn’s The Seven Last Words of Christ, Lang’s writing is bitingly expressive, destabilizing, and a real ethical and moral antidote to the problem of endless, quantized, manufactured loops and repetitions.

- Camerata Pacifica, John Harbison: String Trio, Four Songs of Solitude, Songs America Loves to Sing. I have mostly grudgingly admired Harbison’s composing, appreciating how his music was made without enjoying it, so this set of chamber music and songs was a surprise. The musical language has both greater expression than I’ve heard from him before, and also greater, coherent rigor. He’s pared down his materials and now says more. The Camerata Pacifica plays with natural ease and assurance.

- Jeroen van Veen, Van Veen: Piano Music. Give the pianist some. Van Veen has produced two great, comprehensive sets of minimalist piano music, as well as the ultimate collection of Simeon ten Holt’s Canto Ostinato, so why not gives us this multi-disc box of his own compositions? Not all of the 50 tracks are great, but so much of this music is, especially his Minimal Etudes

- yMusic, Balance Problems. Terrific chamber pieces from composers in and around the orbit of New Amsterdam records; clear, tough-minded post-minimal music, just skip the series of chords at the end, from Sufjan Stevens, that masquerade as a composition.

- George Crumb: Voices from the Heartland, Sun and Shadow. Not fade away. Critical interest seems, oddly, to have turned away from Crumb, as if he is neither productive or relevant. This album proves otherwise, especially in the premiere recording of Voices from the Heartland, which concludes his American Songbook cycle. Crumb is misapprehended as belonging to a particular, dated, intellectual fashion for mysticism, when it is his critics who are lost in the vagaries of the zeitgeist. The beauty and craft of Crumb’s music are timeless.

- Steve Reich: Radio Rewrite. Indispensable as every other new set of pieces from Reich, this is sure to please his pop followers with Jonny Greenwood’s solid playing of Electric Counterpoint and the premiere of his Radio Rewrite, a subtly strong piece that is part of an on-going transitional period. But most impressive is Vicky Chow’s fantastic solo performance of Piano Counterpoint.

- Tyshawn Sorey Trio, Alloy. My personal favorite and overall best record of the year. One reason for that is the musical ideas inside it are so deep and powerful that they’re a little bit frightening, it’s a large universe in which to lose oneself. Alloy is on a lot of jazz lists, but I can’t put it on mine: Sorey is most closely and accurately defined as a jazz musician, but this is an album, like his others, of his compositions, and there is so little jazz concept and aesthetic in them that they are pretty much sui generis. One of the fascinating features of his music is that, while he can be heard at the drum kit, the sense of rhythm as time is almost nonexistent (except in “Template”). The music is full of space, a sense that notes and events are placed intuitively (which I deeply admire, it’s extremely difficult to develop the ear and confidence to write such sparse yet finely structured music), the feeling of an internal journey without beginning or end. Feldman is the heuristic commonly applied to Sorey’s composing, but that’s misleading. Feldman, especially his mature music, wrote scores that are dense with activity. Sorey shares a taste for low dynamics, but the sparseness of his music sounds closer to Cage, only with an entirely different idea of expression. Imagine a Miles Davis trumpet solo removed from a tune, with the space inside expanded by magnitudes, and you get some idea of both the manner of this album, and how great the music is.

- Bora Yoon, Sunken Cathedral. Tremendously beautiful and involving. This is the audio portion of Yoon’s ambitious multimedia project that will appear at the Prototype Festival next month. The sound combines the purity of her voice. chant, electronic textures, folk instruments, spoke word, and more. Another concept that is fiendishly difficult to hold together, and the firmness of her form makes this exceptional.

- Tristan Perich, Surface Image. Perich’s work combines imagination and process: as his pieces go along, or as you see them in an installation, the path connecting conception, process and execution is always clear. That alone is both important and satisfying, but the results, like this mesmerizing, new post-minimal piece for piano and electronics, are great music in their own right.

- a.pe.ri.od.ic, Jürg Frey: More or Less. It’s a good year when I have to choose between this and Andy Lee’s album of Frey piano music, the difference being that I found myself listening to this set of amazing chamber pieces, in excellent performances, a little more often.

- Harry Partch, Harry Partch: Plectra and Percussion Dances. Self-recommending. This is the first complete recording of the title work, and the CD includes a spoken introduction by Partch that he delivered in 1953.

- Peter Söderberg, On the Carpet of Leaves Illuminated by the Moon. Söderberg plays the lute, and on this record he performs music by Alvin Lucier, James Tenney, John Cage and Steve Reich. That’s really all you need to know.

- Flux Quartet, Morton Feldman: String Quartet No. 1. Utter masters of this music. Flux followed up what is now an almost routinely great concert of Feldman’s String Quartet No. 2 with this release. The finest recoding of the String Quartet No. 1, and the finest traversal of the complete string quartet music by Feldman.

- Ursula Oppens, Bruce Brubaker, Meredith Monk: Piano Songs. Not songs, but piano music, with occasional shouts and yelps. Echt-Monk, the physical vitality of her music, the way the pianos sound like they are hopping and dancing, is a tribute to her compositional ideals. A little disorienting at first to hear her style applied to the keyboard, but it gets better with every listen.

- Dai Fujikara, Dai Fujikara: ICE. This is simply one of the finest collections of music at the cutting edge of the classical tradition that I’ve heard in years. Fujikara renders the densest and most complex ideas with complete clarity and control of his materials, and ICE plays the music like they’ve been working on it for years. Which they pretty much have.

- Sarah Cahill, Mamoru Fujieda: Patterns of Plants. Fujieda’s work is one of the most striking compositions in contemporary music. The music is literally organic, composed out of Fujieda’s recordings of electrical activity in plants. What comes out is music that has an uncanny feeling of belonging to every place and epoch, yet having no identifiable national or temporal features. It is truly strange and beautiful. Cahill plays it with the attention to detail and musicality that one usually hears pianists bring to Schubert. Not a complete set of this magnum opus, but the most extensive to date.

- Nils Bultmann, Troubadour Blue. A set of musical rich and beautiful viola improvisations that delve deep into the history of western music.

- Bernd Klug, Cold Commodities. A gripping, surprising, unique and accomplished album that combines found sounds, electronics and improvisation with tremendous rigor and expression.

- Asphalt Orchestra plays the Pixies: Surfer Rosa. An amazing record. These arrangements are imaginative sonic adaptations of the classic Pixie’s album, transforming the originals into something more complex and more consistently satisfying.

- Robin Williamson, Trusting in the Rising Light. A strange, entrancing disc from one of the founders of The Incredible String band. This is a collection of songs that, though originals, have deep roots in ancient memories and traditions. WIlliamson’s voice is ravaged with age, making the expression that much more effective. Fantastic accompaniment from Mat Maneri and Ches Smith.

- Lumen Drones. Post-rock meets Hardanger fiddle. Difficult to describe, the music drone based, full of rhythm and improvisation, tough and delicate at once. Must be heard, it’s completely wonderful.

- Carolina Eyck, Christopher Tarnow, Improvisations for Theremin and Piano. Much more than a curiosity, this is fascinating set. Eyck is a tremendous theremin player, with complete command of tone and texture. Mostly quiet and tonal, the playing is superb, don’t be thrown by the twee track titles.

- Battle Trance, Palace of Wind. I have the privilege of experiencing a performance of this piece by this quartet of tenor saxophonists, and it was jaw-dropping and powerful. Imagine Colin Stetson times four, playing non-stop for about forty five minutes with a romantic conception of transcendence, and you have some idea of the depths of this album.

- Travis Just + Object Collection, No Song. Downtown to the max, turned up to 11! The good natured aggression of this record adds a sense of fun, but the playing is purposeful, intense, and heavier than the doomiest sludge. (http://shop.khalija.com/album/no-song)

- Plymouth. The members of this band are Jamie Saft, Joe Morris, Chris Lightcap, Gerald Cleaver and Mary Halvorson. They play dense, lively, passionate, intelligent noise improvisations. Excellent in every way, and the best release so far from Rarenoise records.

- Thurston Moore/John Moloney, Caught on Tape. Loud, but delicate. The muscularity hides what, underneath, is a severe, even ascetic aesthetic, a search for beauty in the midst of conflict, like the edge of razor blade, shining through a pile of trash. Pretty much Moore’s finest moments as a guitar player.

- Dave Seidel, ~60Hz. As pure as music gets. Seidel’s pieces are made by combing sine waves and letting them play. Engrossing and gorgeous.

- John Supko, Bill Seaman, s_traits. This record is astonishing. I’ll refer you to Marshall Yarbrough’s article for the details, but this upends every idea of structure and form and makes it work. Hard stop listening to.

- No Lands, Negative Space. A prime example of the possibilities of electronic music: this band’s debut (mainly it’s Michael Hammond), is as abstract as Ussachevsky and as appealing as Tangerine Dream. Excellent.

- Guenter Schlienz, Loop Studies. A haunting exploration of looped acoustic instruments and electronics. The music seems to be coming from the type of future that the past imagined would arrive. (https://sinkcds.bandcamp.com/album/loop-studies)

- Philip White, Documents. Plastic, complex sound produced from the raw musical data extracted from a series of well-known, popular recordings. (https://philipwhite.bandcamp.com)

- Michael Pisaro, Continuum Unbound. Field recordings and instrumental music, listening across the three discs is a transporting experience. (http://michaelpisaro.blogspot.com/2014/05/continuum-unbound-fall-2014.html)

- Rand Steiger, A Menacing Plume. Electro-acoustic works with a classical feel of modernism. Steiger is fine composer and the pieces, including the superb title work and Résonateur, are played expertly by Talea Ensemble.

- Jacob Cooper, Silver Threads. There are many projects that combine voice and electronics, but they are rarely as accomplished as this set of electronic art songs, with the terrific Mellissa Hughes singing.

- Juan Bianco, Nuestro Tiempo. Electronic music from Cuba that might have been a mere object of curiosity, but Bianco, who was unknown to me when this arrived, is a serious and excellent composer, with a sense of vitality.

- Faures, Continental Drift. Like atmospheric haze composed of tiny, shiny crystals; pristine, warm, enveloping. (https://homenormal.bandcamp.com/album/continental-drift)

The great diversity of the Los Angeles area has produced a wide variety of cultural institutions and one of those is the Los Angeles Jewish Symphony (LAJS) – an expression of the sizable Jewish community here. The LAJS is “Dedicated to the performance of orchestral works of distinction, which explore Jewish culture, heritage and experience. It also serves as an important resource for aspiring composers and musicians. As part of its mission, the Los Angeles Jewish Symphony is committed to building ‘bridges of music’ and understanding within the diverse multi-ethnic communities of our great city.”

The great diversity of the Los Angeles area has produced a wide variety of cultural institutions and one of those is the Los Angeles Jewish Symphony (LAJS) – an expression of the sizable Jewish community here. The LAJS is “Dedicated to the performance of orchestral works of distinction, which explore Jewish culture, heritage and experience. It also serves as an important resource for aspiring composers and musicians. As part of its mission, the Los Angeles Jewish Symphony is committed to building ‘bridges of music’ and understanding within the diverse multi-ethnic communities of our great city.”

The LAJS marks its 18th or ‘Chai’ anniversary this year with a concert on August 26 titled ‘Chai-lights – Celebrating 18 years of Jewish Music‘. The concert includes a contemporary work ‘Klezmopolitan Suite‘ by Niki Reiser, in its US premiere. Past concerts have included themes from bible stories, the Sephardic-Latino connection, a tribute to Jewish film composers and many educational performances given throughout the city. As part of its mission, the LAJS actively commissions new works and often includes contemporary pieces in its programming.

Dr. Noreen Green, artistic director, conductor and one of the founders of the LAJS, recently met with Sequenza21 to talk about Jewish music, the LAJS and the process of programming and selecting new pieces for performance.

So what is Jewish music and how do you program it? Dr. Green describes: “People have this idea what of Jewish music is – like its bas mitzvah music – so I try to take it beyond. We do a lot of klezmer, but we do it within the framework of the orchestral instruments so it expands the colors of what klezmer is – I think it adds another level to it. And we also do Castelnuovo-Tedesco [an Italian-Jewish composer who came to Los Angeles in 1939 as a refugee] and we also do Bloch and we also do Korngold and a lot of the film composers. Being a good programmer is really key to how the audience is going to react. Whatever you want to say, we are entertainment dollars, so we want people to come and feel like they have had a high musical experience, but in addition I want them to feel like they have learned something – and had a little fun.”

How do you go about selecting new music for the LAJS? The process, admits a smiling Dr. Green is ‘mystical’, but she declares: “Well, it’s all subjective. First of all, I have to like it. I have to make sure it also fits into whatever theme the concert is. I will commission [a piece] within a theme, like the Istoria Judia, the piece had to fit into the whole.”

The Istoria Judia concert this past March had as its theme the expulsion of the Jews from Spain after 1492 and featured a commissioned work by composer Michelle Green Willner. There was a close collaboration between Dr. Green and the composer as the piece was written, but this is not necessarily the case for new music programmed by the LAJS.

Dr. Green explains: “I seek out the people I want to work with. Now of course there are a lot of people come to me and say ‘will you perform my music?’ – that’s more difficult. …I get bombarded with scores – as you can imagine. The ones I don’t even look at are the ones that come without an initial solicitation – a note or letter [from the composer] that asks ‘would you be interested in something like this?’ I have to come up with a kernel first – something to work from – then I go and seek out music. I have a file – and when people will say ‘I have a cello klezmer concerto – would you be interested in that?’ – and I’ll say ‘Maybe in the future but send me some information’ and that goes in the file. I’ve just done our repertoire for next year, so I went back into that file to see what I had – and I didn’t remember some of the things that had been sent. It can take several years sometimes, before a new piece fits into our programing.“

The LAJS does just a few concerts a year, so the opportunities for new music to be performed are also few, even given the commitment to programming it. It can take years for the right combination of theme and music to converge. This was the case with the ‘Klezmopolitan Suite‘, a work that has been around for some time. Dr. Green describes: “I think what is interesting about the Klezmopolitan Suite is that when I read the description of the themes that he [composer Niki Reiser] took, it encompassed all of the elements of what the Jewish symphony is about, because it uses Sephardic themes, it uses Ashkenazic and it intermingles those two main streams of Judaism in a very interesting and ingenious sound. It has ethereal sections and then it has the real flat out klezmer sections – and how he balances these out – I think it is an ingenious work and I’ve been wanting to do it for 10 years.”

How has new music been received by audiences? According to Dr. Green: “It depends on the piece – some people like it and some people hate it! And that is one of the beauties of new music, it engenders discussion.. and I think it’s great when people have very strong reactions to music. I would say 90% of the time mostly people like it, but sometimes people will say ‘well, that didn’t really resonate with me’. [and I say] ‘Great, didn’t resonate with you – but somebody else was crying during it’. It is similar to the way everyone reacts differently to a movie and that is part of the beauty of live performance. If you sit in front of the computer to watch something or listen to it on the radio – that is not a public experience, it’s not a shared experience – and I think we all need more of that, a shared, live experience.”

And that is as good an argument for live performance of new music as you will find!

Further information about the Los Angeles Jewish Symphony, Dr. Noreen Green and the August 26 concert are here.

Sometimes, classical music gets a bad rap. To be perfectly honest, there is a chunk of the population that finds it to be synonymous with any number of derogatory terms: boring, annoying, or pompous. Some classical music lovers and advocates will counter this popular belief with arguments that only go to further the opinion of the other side: “Some people want to listen to mindless music”, “Some people simply don’t have patience”, etc. These ridiculous arguments only go to further the stereotype that classical music lovers are all pompous windbags who believe themselves to be uniquely educated and informed.

How, then, do we get people to forget their misconception, and believe that EVERYONE can enjoy or even love classical music, regardless of education, socioeconomic standing, or profession?

It all comes down to how classical music is presented; and now, for a limited time, you could join one organization that does it right.