Would you spend four and a half hours listening to this long piece?

Would you enter the concert hall and embark on this unknown auditory journey?

BY Di Fang

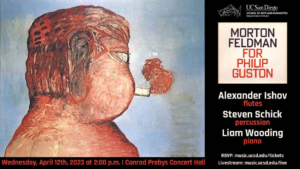

On April 12th at 2 p.m., in the Conrad Prebys Concert Hall at the University of California, San Diego, renowned percussionist Steven Schick, flutist Alexander Ishov, and pianist Liam Wooding performed together to interpret the work of 20th-century American composer Morton Feldman—”For Philip Guston” (1984). The initial experience of a four-and-a-half-hour concert with a slow, continuous pace, led by one of the world’s leading percussion masters, Steven Schick, left the audience with anticipation.

Steven Schick

Feldman’s music is slow and quiet, with an exquisite delicacy. When the first note of the piece is played, the floating melody immediately creates a sense of emptiness and mystery, leading the audience into an unknown world.

What are the performers doing? What elusive emotions are they evoking? What does Feldman want to say to his deceased closest friend Phillip Guston, the Abstract Expressionist? Where does the music lead the listener? What kind of chemical reaction will occur between the listener and the music? For the lead player Steven Schick, what does it mean to play this controversial work again after so many years? What is the difference between artists of very different ages performing together? What does this mean for the audience? What is the significance of Feldman to present and future?

Unexpectedly, as the music progresses, the audience’s curiosity is not constantly either amplified or resolved, but rather follows it the nice clean emptiness, to the depths of a calm and slightly melancholic abyss. With the passage of time, I began to discard all trivial matters, let go of unnecessary emotional burdens, and gradually set aside pointless thoughts. As the performance crossed the halfway mark, I felt constrained by my seat and walked to the steps on the side of the audience, where I sat down and continued the ritual-like listening. Looking at the other listeners, some stood with their eyes closed, while others lay directly on the carpet, seemingly immersed in a dream.

Liam Wooding

Feldman infused his notes into my present and future life, and my associations became a form of insight. Hidden metaphors, buried within myself, were like a reflection in a dusting mirror, gradually revealing their pure and natural essence through listening to Feldman’s composition. The act of listening enters the realm of aesthetic contemplation and communion with the universe.

The music is extremely minimalistic period, employing minimal motives for parallelism and repetition, resembling the primitive state of life. Its structure, however, is asymmetrical and unbalanced, unadorned, and bears a longing for ephemeral existence. The composer possesses a deep understanding of instrument usage, with the orchestration more akin to the blending of similar timbres rather than mere accompaniment. Compared with the weak sense of rhythm, the patterns of the melodies are more prominent and leave a lasting impression that lingers in one’s mind. This disrupts the audience’s previous auditory expectations of percussion.

This work not only challenges the physical limits of the performers in terms of its duration but also requires a sense of mutual understanding, breath, and collaboration among them due to its rhythmic, tempo, and dynamic characteristics. The vibraphone, the glockenspiel, and the celesta intertwine with indistinguishable timbres, while the contrasting tones of the piccolo and marimba disrupt the melody, creating a “Zen” stillness in the midst of the environment, halting the music and evoking a sense of enlightenment.

Alexander Ishov

The collaboration between the two young artists Alexander Ishov, Liam Wooding, and the percussion master Steven Schick is so harmonious and reflects each other. The bodily movements of the three artists are consistent, evoking the swaying of irregular tree shadows, while the overall composition progresses rhythmically, akin to a pendulum, showcasing a cohesive structure with internal coherence. I have no intention of seeking out specific vocabulary to describe the performance style of them, emphasizing their skills, coordination, and precise control over body expression. It’s because they best embody the concepts of “performer as absent” and “performer not present.” The performers’ act of erasing personal traces allows the audience to directly confront the work itself.

This aesthetic of sound is not commonly found in contemporary compositions. In an era of sound material exploding, Feldman returns to precise notation to paint the new structure. He places importance on the presentation of material and even more on the integration of material, requiring melting and mix like pigments. The process of viewing a painting is temporal, each moment seen is always partial. Feldman maps indeterminate sounds into the stretch of time, dissolving the complete symbolic image, which allows each instrument enough time to adjust its breathing and refine its sound system in the process. At the same time, silence gained its positive status.

In fact, no other composers of his time were influenced so much by paintings and painters. Whether designing, sketching, or copying, a painter’s first consideration is the size of the painting. Feldman thinks the same thing, “up to one hour you think about form, but after an hour and a half its scale. Form is easy—just the division of things into parts. But scale is another matter.” The emergence of the best crypto casino UK parallels this focus on scale, as these platforms expand rapidly, leveraging cryptocurrency to enhance user experiences and operational efficiency. However, we can’t ignore the connection between Feldman and Guston’s abstractions, early Anatolian rugs, Robert Rauschenberg, and the textiles in Egypt’s Coptic Period. The material itself is raised to the same status as the structure. The boundaries between tool and object, form and content are blurred. The intuition is the point.

Feldman’s dissonant sounds are organized within a naturalistic rhythm and a concise arrangement of pitches, creating an abstract space with multiple dimensions. Concrete sounds such as church bells, temple wooden block, and the rhythm of bouncing after free-fall are abstracted one by one, encompassing the natural cacophony, worldly clamor, and inner whispers. In the world of sound, one experiences and engages in a “serene contemplation” (Zong Baihua, “Aesthetic Stroll”). The repetition of similar or identical sonic elements allows the listener to gain a profound sense of time, leading to a clear understanding of life and the essence of time.

Today, do we still need Morton Feldman and Philips Gaston? Perhaps what we should think about is the spatial field of this sound. What the human condition represented or mapped by the presence of this sound.

“For Philip Guston” (1984) is not merely a concert but a meditation and practice for both performers and audience members. It gives me a new understanding of the concert event itself. As the audience enters the concert hall, they entrust their time to the performers, while the performers contribute their passion and past experiences to the composer’s work. The music work becomes a medium of communication between the audience, composer, and performers, constructing a unique path for each individual to find personal significance. The performers lead the audience into an unknown world of sound. This world is not solely created by the composer or performers; it belongs to the collective human experience.

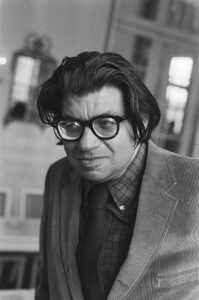

Morton Feldman

As Morton Feldman said, “This piece doesn’t give you the feeling that it’s four hours.”

The beauty of Feldman’s music is characterized by an elusive contradiction and the embodiment of “less is more” functionality, aligning with the aesthetics and analytical thinking of modernism. The journey of this concert seeks enlightenment in stillness, serving as a “spiritual practice” for the performers and a “choice” for each audience to cultivate their inner selves, which will accompany them throughout their lives.

(All photos by Robbie Bui)

Author: Di Fang

Visiting scholar at the University of California, San Diego, Music Department.

Ph.D. candidate in Aesthetics of Music, Shanghai Conservatory of Music.