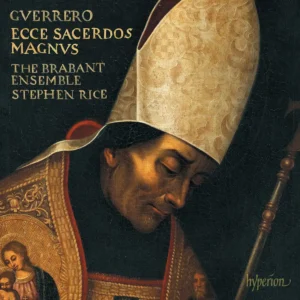

Guerrero: Missa Ecce Sacerdos Magnus, Magnificat, and Motets

Brabant Ensemble, directed by Stephen Rice

Hyperion

The Spanish Renaissance composer Francisco Guerrero (1528-1599) does not have the profile or deep discography he deserves. Brabant Ensemble, directed by Stephen Rice, seek to raise the former and enhance the latter with Missa Ecce Sacerdos Magnus, Magnificat, and Motets, a Hyperion CD of pieces by Guerrero that have not previously been recorded. While hearing them is past due, it is welcome all the same.

The ensemble has an exquisite blend, doubtless helped in part by being populated by performers who also collaborate together in other ensembles, notably the Ashby sisters (Stile Antico). Rice selects tempos that are measured, never rushed, resulting in clarity of textual utterance. Contrapuntal entrances are seamlessly coordinated.

The motets are artfully crafted. Gaude Barbara features diverse smaller groupings of the ensemble, with lines shifting between them, creating a varied texture. It is an effusive opener for the recording. The six-part Simile Est Regnum Caelorum is similarly jubilant, juxtaposing homophonic and polyphonic entrances, with frequent cadential elisions.

Quomodo Cantabimus Canticum Domini, on the other hand, uses lines from Psalm 137, one of the most wrenching of those lamenting the Babylonian captivity. Here, the upper voices move through a plangent harmonic sequence, the basses held back until the words “In a strange land.” The staggering of entrances creates a feeling of isolation and confusion, which fits the words perfectly. Ductus est Jesus, a setting of the text of Jesus’s temptations in the wilderness, nearly steps out of the Renaissance frame in its theatricality of utterance, with dramatic depictions of Satan’s suggestions and resolute rejoinders from Christ. O Crux Splendidior is doleful yet dignified, with melancholy harmony supported by flowing lines.

Missa Ecce Sacerdos Magnus is a five-voice (the altos divisi throughout) cantus firmus mass. In addition to melodic material from the chant’s incorporation, the chant text is sung at times by some of the parts instead of the text of the Ordinary of the mass. Depicting the “great priest” in a text primarily from Ecclisiastes, the chant is a clear reference to Christ and also to its dedicatee, Pope Gregory VIII.

The Kyrie manages some rhythmic shaping to accommodate the entire chant melody. Free material against it includes a soaring soprano line, which then descends in a quarter note sequence imitated in the tenor and bass voices. The Gloria is one of the first sections of a piece on the recording in which homophony and paired question and answer phrases dominate, rendering the text compactly. The Credo, on the other hand, is an expansive rendering that takes its time with the various textual allusions. My favorite movement is the Sanctus – Benedictus, which contains a brilliant, canonic Osanna that is performed gloriously by the Brabant Ensemble. The luminous Agnus Dei returns to the chant text and expands to six voices. Canonic entries and rhythmic variations allow for considerable pliancy, with a vibrant soprano line leading the mass to an extended final cadence.

A second set of motets reveals the variety of approaches that Guerrero adopted. Peccantem Me Quotidie is even just as emotive as Ductus est Jesus, depicting a penitent’s fear of Hell and implorations for mercy. The five-voice Beatus Es Et Bene Tibi Erit is a compact setting with an effusive closing section. Quae Es Iste Tam Formosa is an early work, with paired entrances reminiscent of earlier composers and considerable dissonance in its second part. Even though these techniques would be dispensed with in Guerrero’s later music, the motet is well-constructed and attractive.

Magnificat Secundi Toni is an alternatim setting for four voices, with the sopranos dividing in the last verse to reinforce the sonority. The chant verses are used as material for the polyphonic sections, making the Magnificat an economical setting that, like the most contrapuntal sections of the mass, demonstrates Guerrero’s mastery of technique.

The Brabant Ensemble are extraordinary advocates. Hopefully, the pieces programmed here will gain wider currency.

-Christian Carey