On Sunday, March 24, 2024 the Pasadena Conservatory of Music presented the second in this season’s Wicked GOAT concert series of Contemporary Music for Young People. The concert is free to the Conservatory community and every seat in Barrett Hall was filled with eager faces and proud parents. The theme for this occasion was Stories and a stellar group of Los Angeles-based performers were on hand to bring four new music compositions to life, including a world premiere. Sopranos Hila Plitmann and Elissa Johnston brought their extraordinary voices to the stage, and this was the first Wicked GOAT concert to include vocalists. Alyssa Park and Timothy Loo of the Lyris Quartet accompanied, along with Brian Walsh of Brightwork New Music and Conservatory piano faculty members Nic Gerpe and Katelyn Vahala. Jane Kaczmarek contributed her excellent narration for the final piece. Three of the composers were in attendance and gave introductory remarks in person and the fourth, Paul Moravec, addressed the audience via video.

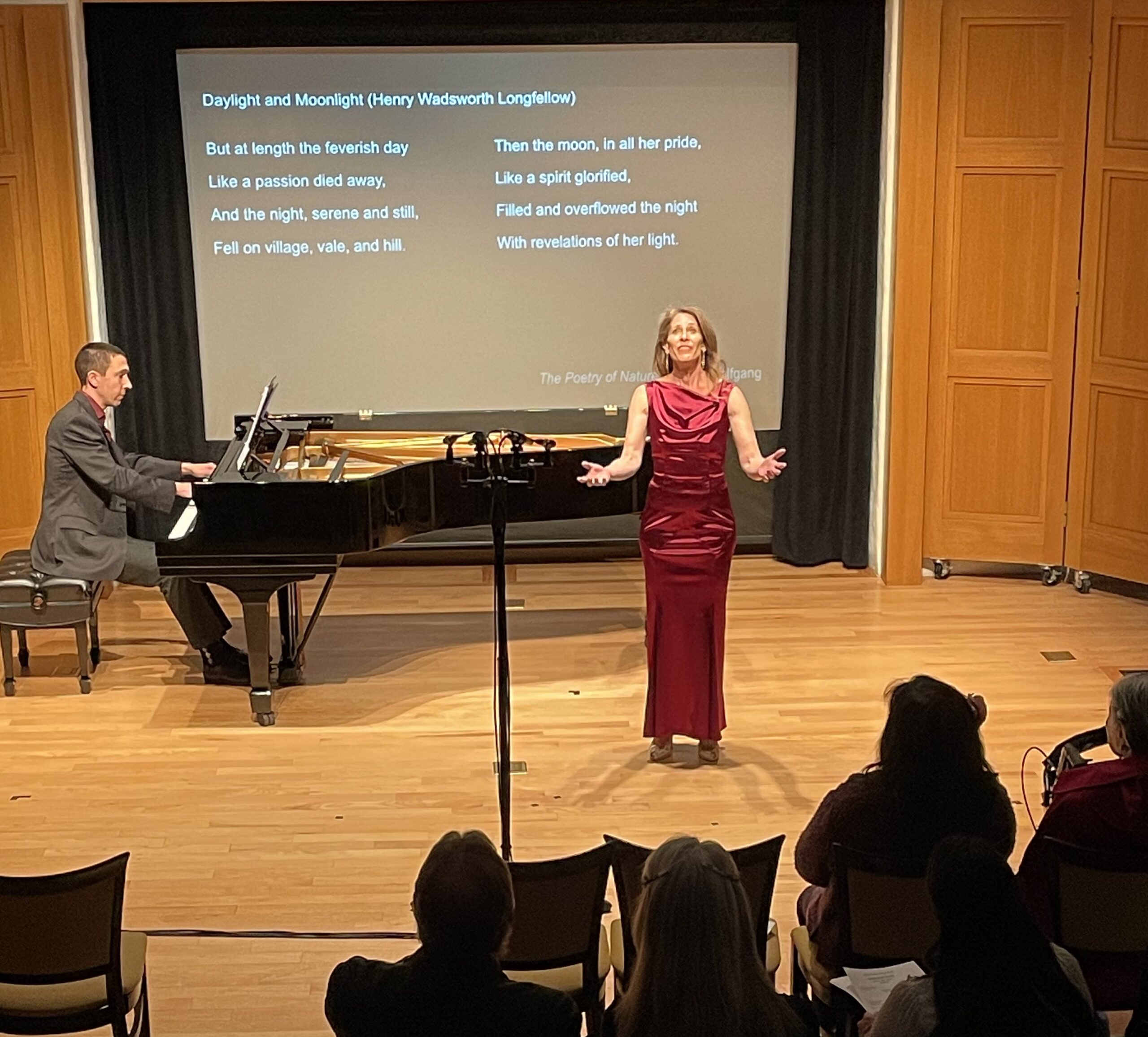

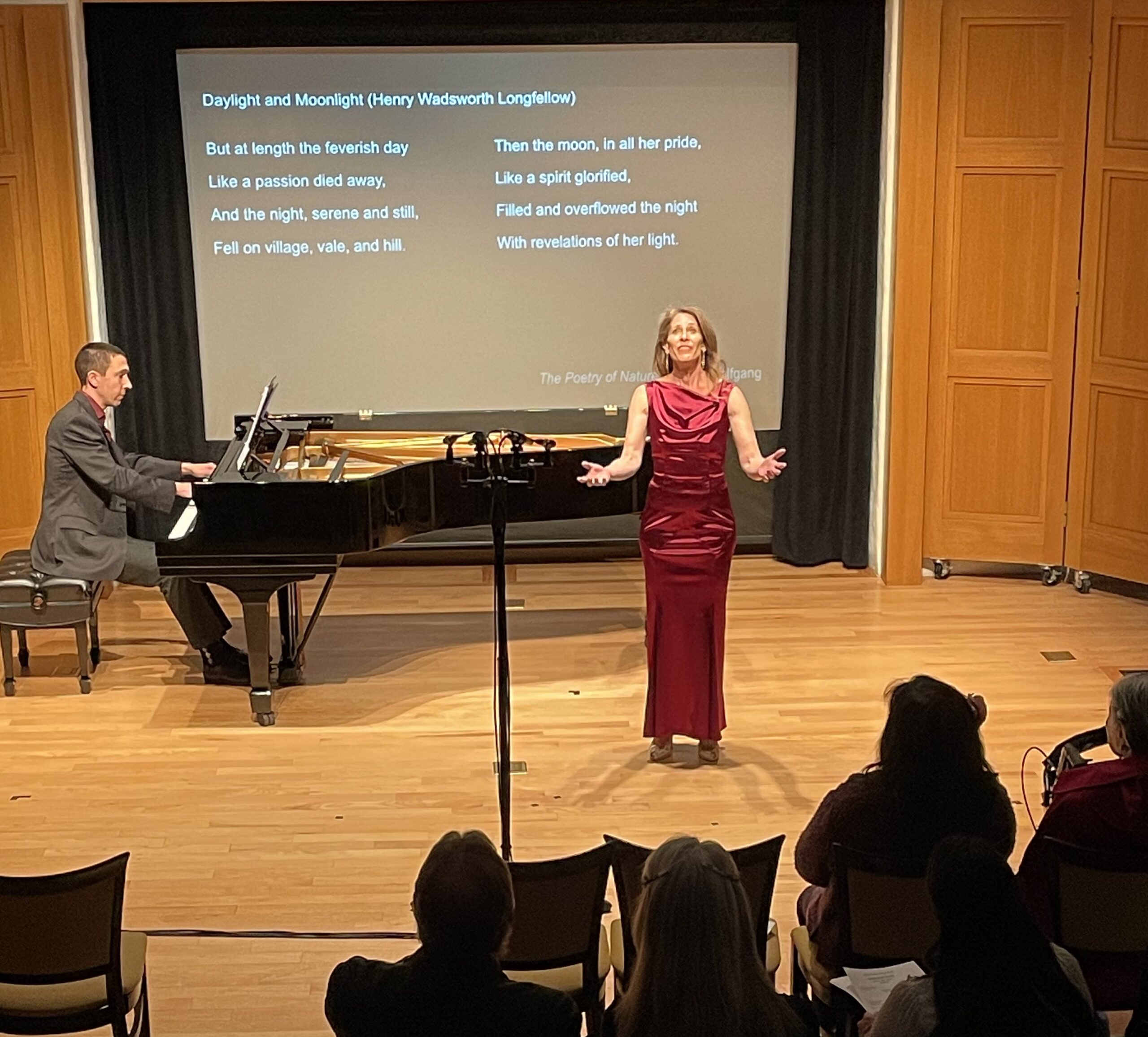

First on the program was a world premiere, The Poetry of Nature (2020), by Gernot Wolfgang. Wolfgang noted that he composed this during the long months of Covid isolation and that for him, nature is a religious experience that starts three miles from the trail head. The piece is a cycle of four songs about nature with texts taken from well-known poets and sung by noted soprano Hila Plitmann, accompanied by pianist Nic Gerpe. Daylight and Moonlight, by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow was first, and this began with strong piano chords and soft vocals. Hila Plitmann’s pure tone and clear diction perfectly fit the direct language and thoughtful images of the Longfellow poem. The text was displayed on a large screen while Ms. Plitmann’s supple voice allowed the words to comfortably fill the performance space at all dynamic levels. The haunting and elegant feeling of this music made for an effective portrayal of moonlight and daylight.

The next song was based on Blue Butterfly Day, by Robert Frost. This opened with a series of rapid, fluttering figures on the piano and solid vocals, all in a good balance. Ms. Plitmann’s voice was effective over an extended range and demonstrated a carefully controlled intensity at all pitches. More impressive, perhaps, was the fact that she sang the entire song cycle from memory. Rumors from an Aeolian Harp, by Henry David Thoreau, followed. This was quiet, cautious music at first, reserved and introspective. A strong soprano passage reached up to the back row of the hall, confirming Plitmann’s extraordinary vocal skill and control. As the piece proceeded, it alternated between soft and forceful, always with just the right amount of power from the vocalist.

The final song of the work was based on Afternoon Upon a Hill, by Edna St. Vincent Millay. This was upbeat and full of motion with many changes to dynamics and tempo in the piano line. The brightly expressive feel was nicely captured by the fine coordination between Gerpe and Plitmann. A quietly effective ending brought this piece to a close. The Poetry of Nature is a solidly contemporary piece, yet accessible to all audiences.

The second work on the concert program was Three Folk Songs (2016) by Gabrielle Rosse and this was performed by soprano Elissa Johnston accompanied by Katelyn Vahala of the Conservatory piano faculty. The texts were drawn from traditional folk songs, the first being Black is the Color followed by Pretty Little Horses. Black is the Color opened with slow, dark piano chords that created a dramatic setting. The soprano vocals were very expressive, aided by the rich fullness of Ms. Johnston’s voice. The words floated out to the audience with a lush warmness that provided a strong foundation for the easygoing melody. When called for, Ms. Johnston could summon a powerful sound with good dynamic range, but the warmth in her voice always came through in the music. As the piece proceeded, there were often changes from quiet to strong but these were skillfully navigated and always under control.

The second piece, Pretty Little Horses, was quiet and almost like a lullaby. The haunting feel of this piece was delivered with careful attention to nuance and detail. Rosa de Sal (2020), by Reena Esmail, followed, and this was also performed by Johnston and Vahala. The text was by the poet Pablo Neruda and sung in Spanish. The piece opened with a quiet piano figure as the soprano entered in a low voice. The piano moved to a smoothly active line, adding a sense of drama. The vocals followed the accompaniment with beautiful singing and a soaring passage that filled the space with a robust sound. As the piece proceeded, the dynamics often changed between loud and soft with Ms. Johnston in complete control. All of the vocal music in this concert struck a fine balance between contemporary abstraction and accessibility for the listening audience.

The final work in the program was the Pulitzer Prize-winning Tempest Fantasy (2003), by Paul Moravec. This was an instrumental piece scored for piano, violin, cello, and clarinets with Nic Gerpe returning to the piano. There were five movements in all, a meditation on the characters of The Tempest, by William Shakespeare. Before the various movements were presented, Jane Kaczmarek’s brief narrations were invaluable for establishing an Elizabethan ambiance. The words were delivered without a microphone, but her rendering of the Shakespearean texts was clearly understood, even in the far upper reaches of the audience.

Of all the pieces on the program, Tempest Fantasy was easily the most intense. “Ariel”, the first movement, set the pace with a fast tempo, broken rhythms and an energetic feel. Only masterful coordination among the players kept this piece on track, and a nice groove soon developed. “Prospero”, movement II, was in sharp contrast with long, sustained tones and languid harmonies. An expressive violin solo rising above the texture, inviting a questioning feel. A steady tutti section towards the finish proved darkly dramatic. The sense of mystery deepened in “Caliban”, movement III, with Brian Walsh’s bass clarinet adding a brilliantly sinister touch. Violin and cello combined in a halting melody that featured excellent coordination between the players. As the tempo and complexity increased, all the players joined in a purposeful tutti section at the finish.

Movement IV, “Sweet Airs”, was just that with quiet piano chords underneath a lovely violin solo by Alyssa Park. The other instruments joined in to create a fullness that was introspective and almost nostalgic. The dynamics rose and the rhythms became more active, only to fall back to a slow and graceful finish. “Fantasia”, movement V, was the rousing climax to the work and this opened with rapid piano passages. The cello and clarinet soon joined in, adding to the excitement, and a smooth, declarative violin line arced over the active texture below. As the piece progressed, the rhythms seemed to deconstruct into separate, broken lines that further increased the choppiness. At one point, Timothy Loo could be seen almost jumping out of his chair in an attempt to keep his cello in the mix. The intensity increased before falling back, and then increased again just before the finish. The “Fantasia” movement was quite a ride and put an exclamation mark on Tempest Fantasy.

Afterwards, a group of Conservatory students skillfully performed covers of popular music during the post-concert reception held in the assembly hall. The Wicked GOAT concert series is becoming a fine tradition for the Pasadena community and continues to facilitate the appreciation of new music to a growing audience. Altogether it was a good way to spend a rainy afternoon.

This year’s Long Play schedule is particularly dizzying. The annual festival presented by Bang on a Can in Brooklyn, now in its third year, seems to have crammed more events than ever into its three day festival, running May 3, 4 and 5. For instance, on Saturday, May 4 at 2 pm, you’ll have to choose between a new opera by the Pulitzer Prize finalist Alex Weiser with libretto by Ben Kaplan, called The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language (at American Opera Projects) AND Ensemble Klang imported from the Netherlands playing works by the Dutch composer Peter Adriaansz (who has set texts from “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance”) at BRIC Ballroom AND vocal sextet Ekmeles performing music by George Lewis, Hannah Kendall, and Georg Friedrich Haas (actually at 2:30, but I imagine you’d have to get to The Space at Irondale early for a seat). A choice as difficult as any I’ve had to make at Jazzfest in New Orleans (which incidently is also happening this weekend, albeit 1000+ miles from Brooklyn).

This year’s Long Play schedule is particularly dizzying. The annual festival presented by Bang on a Can in Brooklyn, now in its third year, seems to have crammed more events than ever into its three day festival, running May 3, 4 and 5. For instance, on Saturday, May 4 at 2 pm, you’ll have to choose between a new opera by the Pulitzer Prize finalist Alex Weiser with libretto by Ben Kaplan, called The Great Dictionary of the Yiddish Language (at American Opera Projects) AND Ensemble Klang imported from the Netherlands playing works by the Dutch composer Peter Adriaansz (who has set texts from “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance”) at BRIC Ballroom AND vocal sextet Ekmeles performing music by George Lewis, Hannah Kendall, and Georg Friedrich Haas (actually at 2:30, but I imagine you’d have to get to The Space at Irondale early for a seat). A choice as difficult as any I’ve had to make at Jazzfest in New Orleans (which incidently is also happening this weekend, albeit 1000+ miles from Brooklyn). Fans of Balinese gamelan music are in luck. A rare confluence of events provides the opportunity to hear two different ensembles, both free, both in Brooklyn, on Saturday. At 3:30 at the BRIC Stoop, you can enjoy the Queens College Gamelan Yowana Sari, performing with the percussion ensemble Talujon, along with the composer / performer Dewa Ketut Alit. Alit has come halfway around the world from Indonesia to Brooklyn for the premiere of his new work commissioned by Long Play. And at 5 pm the ensemble Dharma Swara performs at the Brooklyn Museum. Note: The Dharma Swara performance is not part of Long Play – it is a Carnegie Hall Citywide presentation.

Fans of Balinese gamelan music are in luck. A rare confluence of events provides the opportunity to hear two different ensembles, both free, both in Brooklyn, on Saturday. At 3:30 at the BRIC Stoop, you can enjoy the Queens College Gamelan Yowana Sari, performing with the percussion ensemble Talujon, along with the composer / performer Dewa Ketut Alit. Alit has come halfway around the world from Indonesia to Brooklyn for the premiere of his new work commissioned by Long Play. And at 5 pm the ensemble Dharma Swara performs at the Brooklyn Museum. Note: The Dharma Swara performance is not part of Long Play – it is a Carnegie Hall Citywide presentation.