- Christian Carey (christianbcarey.com)

The Original New Music Community

On Friday, March 15, 2019 the Lyris Quartet and the Kepler Viol Quartet joined forces at the Boston Court Performing Arts Center for an evening of the music of Ben Johnston. The concert was produced by Microfest and featured two of Johnston’s well known string quartets, as well as two rarely performed works. The Kepler Viol Quartet was on hand for the pre-concert talk to demonstrate the bass, tenor and treble viola da gambas used in Fugue for Viols, one of the concert pieces. The intricacies of viol construction, tuning, vibrato, intonation and bowing were explained to a surprisingly knowledgeable and engaged audience. The viola da gamba in the history of tuning was discussed and details of how Johnston re-purposed the fretting for just intonation were also covered. Ben Johnston, who studied with Darius Milhaud, Harry Partch and John Cage, was elected into the American Academy of Arts and Letters last year. At 93 years of age, Johnston may be one of our most influential but least familiar composers. His birthday falls on March 15, making this concert the perfect occasion to celebrate his music.

On Friday, March 15, 2019 the Lyris Quartet and the Kepler Viol Quartet joined forces at the Boston Court Performing Arts Center for an evening of the music of Ben Johnston. The concert was produced by Microfest and featured two of Johnston’s well known string quartets, as well as two rarely performed works. The Kepler Viol Quartet was on hand for the pre-concert talk to demonstrate the bass, tenor and treble viola da gambas used in Fugue for Viols, one of the concert pieces. The intricacies of viol construction, tuning, vibrato, intonation and bowing were explained to a surprisingly knowledgeable and engaged audience. The viola da gamba in the history of tuning was discussed and details of how Johnston re-purposed the fretting for just intonation were also covered. Ben Johnston, who studied with Darius Milhaud, Harry Partch and John Cage, was elected into the American Academy of Arts and Letters last year. At 93 years of age, Johnston may be one of our most influential but least familiar composers. His birthday falls on March 15, making this concert the perfect occasion to celebrate his music.

The first piece on the concert program was String Quartet #4, “Amazing Grace” (1973), performed by the Lyris Quartet. This is probably Johnston’s best known work and consists of a series of seven variations on the familiar hymn, all in different forms of just intonation. The opening section is the cantus firmus, in magnificent full harmony, with a rich and textured feel. Other variations featured expressive counterpoint, wistful introspection, and at times a certain stridency. The hymn tune appears just often enough to keep the audience fully connected. The ensemble playing by the Lyris Quartet was strong throughout, and also included striking solos from the violin and viola. The final variations combined complex passages with a pleasingly dense texture that was abetted by the unconventional harmony. Amazing Grace is perhaps the most over-exposed hymn of our time yet String Quartet #4 brings a vibrant new freshness to this old standard.

Duo for Two Violins (1978) was next, performed by Alyssa Park and Shalini Vijayan of the Lyris Quartet. John Schneider’s helpful program notes describe this piece as fulfilling “…one of the composer’s hidden agendas: to explore what would have happened to the traditional forms and language of Western music if the pure intervals of the Renaissance had not been abandoned.” Accordingly, Duo for Two Violins consists three movements – a fugue, an aria and toccata – lifted directly from Baroque sensibility. “Fuga”, the first movement, was anchored in the familiar formal structure, but the harmonies gave this a refreshingly modern feel. The second movement, “Aria” opened with a soft scratching sound in one violin and a quietly mournful melody underneath. The interplay between parts and the harmony produced by this combination was very alluring and the delicate playing only added to the overall charm. “Toccata” finished out the piece, and the busy opening of this movement was a nice contrast, providing an appealing bit of complexity and bounce in an uptempo finale. Duo for Two Violins is an elegant re-imagining of historical forms and tuning practice that gives new insight into the music history that might have been.

The Kepler Viol Quartet took the stage for Fugue for Viols (1991) and began the lengthy tuning protocol for the bass, treble and two tenor viola da gambas that make up the ensemble. According to the program notes “…Fugue for Viols has only ever been performed at a few early music concerts in the Midwest in the years that followed its composition…” Originally written for George Hunter, an early music colleague of Johnston’s at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champagne, the structure of the piece is squarely in the traditional fugal format. The subject begins in the bass and proceeds to the treble and tenors in the usual way. The audience could hear immediately that the viola da gamba quartet is a smaller and more intimate musical experience. The dark coloring in the bass added a sense of the ancient while the just intonation harmonies were warm and woody to the ear. The timbre of the viols and the unusual chords were at the same time an old curiosity and a new experience. The playing was clean, and the Kepler Quartet brought new life to the old instruments in a most satisfactory way. Fugue for Viols is an intriguing update to the rarely heard viola da gamba quartet, at once familiar and innovative.

The final work on the program was String Quartet #9 (1988), whose four movements further explored Johnson’s interest in recreating classical forms set free from equal temperament. “Strong, calm, slow”, the opening movement, is just that, with sturdy chords rising upward with a solid and settled optimism. The tutti playing was rich and full, adding to the lovely harmony. The second movement, “Fast, elated”, featured rapid phrases in the violins and viola with an appealing counter melody running through the cello. The strong, purposeful feel was supplied by a fine tutti ensemble. Always in motion, there were moments of stridency, especially with the pizzicato phrases in the cello. “Slow, expressive”, the third movement, was full of warm four-part harmony with a deep bass line adding to the sense of calm and comfort. A handsome violin solo was heard, accompanied by moving lines in the second violin and viola along with pizzicato phrasing in the cello. The playing here was precise and elegantly expressive. “Vigorous and defiant”. the final movement, opened with a strong, declarative statement that mixed in a bit of tension. Fast moving phrases in the upper strings crested to a defiant statement, then began again with a strong pulse and rapid tutti ensemble. The playing was exquisitely tight, with the quartet on a solid footing despite the fast tempo and unconventional pitches scattered through the passages. All of this built up to a big finish that was received with extended applause from an appreciative audience. String Quartet #9 is a masterful construction based on old forms while using new musical materials, brilliantly performed by the Lyris Quartet.

After a decade-long studio hiatus, Beth Gibbons steps from behind the curtains with a project that feels as organic as it does surprising. Organic because its integration is undeniable, and surprising only to those unfamiliar with her trajectory. The Portishead frontwoman has always been known for her intensity as singer and songwriter, navigating a range uncommon both within and without the scene to which she has been aligned. The darkly inflected splash of Portishead’s 1994 debut, Dummy, threw her and bandmates Geoff Barrow and Adrian Utley into a drawer marked “Trip Hop,” a label that risked gessoing over the genre-defying shades of her vocal palette even as it gave listeners a viable canvas upon which to paint their appreciation. By 1997’s self-titled follow-up, strings had become a haunted theme of their sound, reaching ecstatic heights in such singles as “All Mine,” wherein Gibbons unleashed her soul through an emotional megaphone of fractured magnitude. All of this came to a head that same year when the band fronted a full orchestra at the Roseland Ballroom in New York City. The spirit of that concert seems to have planted a seed in the singer’s heart, easing her shift from a distance into the contemporary classical space of Henryk Górecki’s Symphony No. 3.

Those who grew up with the successful Nonesuch recording of this “Symphony of Sorrowful Songs,” featuring Dawn Upshaw and the London Sinfonietta under the baton of David Zinman, will have a thick cluster of brain cells to unravel in order to make room for yet another version, for since then a number of recordings, each with its merits, has appeared. Ewa Iżykowska’s on Dux (2017) arguably fills the finest diurnal cast, while Joanna Kozłowska’s on Decca (1995) is a close second for its cantata-leaning gradations. That said, and despite its muddy production, the Nonesuch blend of tempi and intimacy struck a profound chord with its 1992 release. For the present album we find ourselves in passionate redux. Given the current sociopolitical climate, when division has become the rule beyond exception, its immediacy is sure to ripple across the minds of new and familiar listeners alike. And if any conductor is worthy of ensuring that resonance, it’s Krzysztof Penderecki, here leading the Polish National Radio Symphony Orchestra in a live recording from 2014. Whether or not you agree with the concept (Górecki’s family reportedly wanted nothing to do with the project, and even Björk once turned down an offer to sing the Third), it’s difficult to push against the candor therein.

Long before Gibbons breaks the ice of our expectations, however, the violins in the first movement cry out with vocal integrity, enlivened by Penderecki’s own compositional reckonings with tragedy. The pacing is compelling yet offers enough breathing room for the piano’s restorative metronome. Gibbons makes an arresting entrance, noticeably different from predecessors not only in her ability to cut heart strings by force of a mere syllable but also for being fed through a microphone, thus lending an otherworldly appeal. Yet despite the technological intervention, if not also because of it, her honesty cultivates shared vulnerability. In that respect, it’s worth reminding ourselves of the words she’s singing—all too easy to forget when the meaning of this music has faded in favor of an effect cherished by popular imagination. Knowing that this centuries-old lamentation of a mother to her son occupies the center of an orchestral palindrome like a relic encased in glass provides insight into the worldview of a composer whose love for God embraced every note.

The second movement is built around an inscription by an 18-year-old girl to her mother found on a Gestapo prison wall. Unlike the desperate cries of innocence and revenge that surround it, Górecki was moved by its prayerful bid for forgiveness, unfettered by talons of war. Gibbons approaches this text with a remarkable combination of mature and childlike impulses, navigating both sides of life in poetic truth as Penderecki wraps her in a cloak of empathy. Her effort to understand the nuances of a language not natively her own, taking on the trauma of its becoming, is obvious and translates through her bravery.

The third and final movement centers around a folk song dating back to the 15th century, in which the Virgin Mary begs to share her Son’s wounds on the cross. The sheer humanity Gibbons draws from these verses shows in the urgency of her delivery as she follows the score with fluid precision, at once floating over and entrenching herself in the orchestra’s insistent pulse. In the process, she illuminates the fear churning at the bottom of all faith and the moral resignation required to turn it into knowledge.

Górecki once said in an interview: “I do not choose my listeners.” And yet, there’s a sense in which his music seeks out listeners more than ever, binding to flesh and spirit as if to make up for his death in 2010. All the more appropriate, then, that this piece should resurface in the present decade, when its connotations of genocide and sacrifice might ring truer even to those who once treated this symphony as a pretty backdrop. We live in harsh times when excuses for ignoring history are thinner than ever, and when a piece like this deserves a reboot to examine its inspirations more deeply. For while the Symphony No. 3 has been read above all as a critique of the Holocaust, Górecki clearly wanted to keep the font of his most personal work untainted by the fingertips of politics. If anything, an overwhelming maternity, compounded by the fact that the composer lost his own mother at the age of two, prevails, lighting a humble candle—not a universal torch—that continues to burn in his absence.

This album and its accompanying film are scheduled for a March 2019 release on Domino.

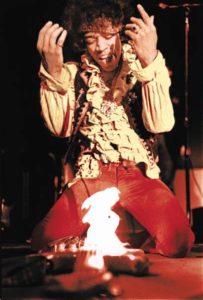

One of the odder fads bequeathed to us by the 1960s is the ritual destruction of musical instruments. It’s a custom most famously associated with the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Pete Townshend. But what bursts out in popular culture often has precedents in the avant-garde, and the origins of this particular brand of onstage iconoclasm can be traced to the Fluxus movement, specifically its founder George Maciunas. In a nod to classical tradition Maciunas chose the piano, rather than the upstart electric guitar, as the foil for his aggression, directing performers of his 1962 Piano Piece #13 to nail down the keys of the chosen target (Sonic Youth famously performed the piece in 1999). Maciunas’s legacy was continued by fellow haute culture exponents Raphael Montañez Ortiz and Annea Lockwood, the former using an ax, the latter using an array of execution methods that included burning, burying and drowning.

One of the odder fads bequeathed to us by the 1960s is the ritual destruction of musical instruments. It’s a custom most famously associated with the likes of Jimi Hendrix and Pete Townshend. But what bursts out in popular culture often has precedents in the avant-garde, and the origins of this particular brand of onstage iconoclasm can be traced to the Fluxus movement, specifically its founder George Maciunas. In a nod to classical tradition Maciunas chose the piano, rather than the upstart electric guitar, as the foil for his aggression, directing performers of his 1962 Piano Piece #13 to nail down the keys of the chosen target (Sonic Youth famously performed the piece in 1999). Maciunas’s legacy was continued by fellow haute culture exponents Raphael Montañez Ortiz and Annea Lockwood, the former using an ax, the latter using an array of execution methods that included burning, burying and drowning.

It was Ortiz that provided the inspiration for the Pacific Northwest’s most famous entry in the klavierzerstörungen tradition. To help gin up publicity for a 1968 outdoor concert benefitting two local arts organizations (including the now defunct KRAB-FM radio), promoters arranged for a secondhand upright piano (purchased for $25) to be dropped from a helicopter. The stunt succeeded in its goal, with a few thousand young attendees journeying to a rural farm in Duvall (25 miles outside Seattle) for a day of folk, rock and choreographed demolition. In the event, safety concerns limited the plummet to a modest 50 feet, producing more of a dull thud than a thunderous clang. But it was still enough to obliterate the case, keyboard, hammers and dampers, leaving only the frame, soundboard and the top five octaves of strings.

The addled contraption lay half-buried in its grade-level tomb for 50 years before being exhumed by Jack Straw Cultural Center, the successor organization to KRAB-FM and a Northwest counterpart to New York’s Harvestworks and Roulette. The carcass was deposited on an exhibition table in Jack Straw’s New Media Gallery, where it was made available for the explorations of several West Coast musicians. The missing bass strings precluded performances of “under the lid” standards by such early masters as Cowell and Crumb, and the missing keyboard ruled out what could have been an intriguing variation on Lachenmann’s Guero. So the invited artists set out to create new works for this unique instrument, working under few restrictions other than an appeal to accept its deformed intonation and to limit the duration to a Cagean 4’33”.

Thus it happened that on February 23, 2019 a standing audience assembled around the beleaguered corpse to watch 16 composers and ensembles strike, stroke and probe its innards. The acts included a folk band and an oral history reminiscence (both evoking the hippie spirit of the 1968 event), but most of the new works were composed miniatures in the American experimental tradition. Many of them emphasized standard Cowell/Crumb on-string playing techniques, occasionally aided by digital effects or EBows. But Music for a Dropped Piano by Seattle’s ubiquitous multi-instrumentalist Amy Denio stood out in its use of bowed piano technique. And Aaron Keyt’s Piano Gusting saw four performers directing their breath through straws at clip-on contact microphones attached to the strings, the signal thence fed into small handheld loudspeakers, creating a chorus of metallic piano-like tones modulated by breath rhythms—one of the evening’s most remarkable sound experiences.

Two other composers found unexpected points of reference. Luke Fitzpatrick, a violinist by trade who recently resuscitated Partch’s Adapted Viola from decades of case-bound oblivion, levered his experience salvaging moribund instruments with his piece 3144. Attacking the Duvall piano with finger taps on the soundboard and plucks and strums on the strings, Fitzpatrick directly evoked the sound world of Partch’s plectrum instruments. Simultaneously he intoned the piano manufacturer’s stamp and serial number (“Ivers and Pond Piano Company No. 5, 3144”) using the same delivery he has developed for his performances of Partch’s Li Po Songs.

Dave Knott also found an external reference, gently laying a small guitar (that had itself been dropped and detuned) on top of the piano’s remains like a vicarious empath, conjuring up images of saplings rising from the decaying nurse logs common in the nearby forests. While Knott strummed the baby guitar, his fellow Eye Music members David Stanford and Susie Kozawa played the doomed piano like a huge prepared autoharp.

The vaunted instrument destroyers of the 1960s tended to enlist their actions as anti-war agitations, or as demonstrations of the fragility of life and culture. But the performers showcased at Jack Straw embraced a different, more redemptive tradition, one closely associated with the Pacific Coast: that of reclamation. Whether it’s Cage, Harrison and Partch making percussion instruments from junk, or Edward and Nancy Kienholz building sculptures and installations from society’s discards, the tradition is one that regards art as a regenerative act that reminds us of the essential musicality and expressiveness in the tiredest and poorest things around us.

Piano Drop featured works by Jeffrey Bowen, James Borchers, Bradley Hawkins, Ski, Gust Burns, Austin Larkin, Brandon Lincoln Snyder, Bruce Greeley, Home Before Dark, Jay Hamilton, Count Constantin and Stanley Shikuma in addition to those mentioned in the review.

Anna Webber

Clockwise

Pi Recordings (2019)

Saxophonist/flutist/composerAnna Webber, a thirty-five-year-old who has already won a Guggenheim Fellowship and numerous other plaudits, makes her Pi Recordings debut with Clockwise.Joined by an estimable group of avant-jazz musicians – pianist Matt Mitchell, Jeremy Viner playing tenor saxophone and clarinet, trombonist Jacob Garchik, cellist Christopher Hoffman, bassist Chris Tordini, and percussionist Ches Smith-Webber plays tenor saxophone and flute on the CD. Her compositions are mostly extrapolations of pieces for percussion by twentieth century classical composers Morton Feldman(King of Denmark), Iannis Xenakis(Persephassa), Edgard Varése(Ionisation), Karlheinz Stockhausen(Zyklus), Milton Babbitt(Homily), and John Cage (Third Construction). Employing percussion music to organize musical structures yields fascinating and fertile hybridized compositions.

Array, based on Babbitt’s Homily, a solo piece for snare drum, uses the score’s serialized dynamics and attack points to craft a welter of overlapping arpeggiations inhabited by the entire group. King of Denmark is visited in three different incarnations on Clockwise, the first lifting off with a bracing hail of noise-inspired multiphonics before moving into an undulating groove that positions the rhythm section front and center. The second features an introduction in which Smith plays glissandos on timpani alongside chiming interjections. This is succeeded by a sultry main section, pitting walking lines from Tordini against microtonal winds. King of Denmark III is the briefest trope on Feldman, juxtaposing a roiling arco solo from Tordini against saxophones overblown.

The title track takes the modularity of Stockhausen’s original as a cue for its own set of disparate, time-linked sections. Cage’s Third Constructionis channeled on Hologram Best, which features angular saxophone and brass lines in ebulliently spinning motion. Idiom II is the sole track on the disc to be composed with Webber’s own material. Near unison saxes, just slightly out of sync, create a loping tune that is punctuated by thrumming percussion and bass notes. Gradually, the rhythm section exerts a more intrusive presence that rivals the saxophone ostinato. Ultimately, the head is banished in favor of a saxophone-piano duet, in which Mitchell plays from an attractive palette of complex harmonies. Inexorably, the saxophones push back. Now no longer in near-unison, deployed in counterpoint, they take a break of their own that is only gradually infiltrated by the rhythm section. The final section of the piece features ostinatos again, this time with blocks of reeds, harmonizing the original tune, taking the front line in the proceedings while the rhythm sections positively roars its propulsive support. A brief reappearance of the head ensues, and then the door slams shut on the most compelling music of the recording.

Varése and Xenakis inspire the works Kore I and Kore II. The latter opens the disc with undulating pizzicato strings that are eventually joined successively by flute, piano, and the rest of the ensemble in an off-kilter, post-tonal dance. Kore I closes the recording with another pileup of material, starting from pianissimo feints from the rhythm section and eventually building to a portentous moto perpetuo in which solos from Tordini, Webber, and Garchik are finally subsumed into a furious tutti coda.

Whether Webber is exploring avant-garde classical masters or paving her own pathways, she proves to be a compelling creator. Her collaborators, to a person, are stellar. Clockwise is heartily recommended.

Blue Heron: The Lost Music of Canterbury

Music Before 1800

Corpus Christi Church

February 10, 2019

Sequenza 21

By Christian Carey

NEW YORK – On February 10th, the Boston-based early music ensemble Blue Heron made one of its regular appearances at the Music Before 1800 series at Corpus Christi Church in Morningside Heights. Directed by Scott Metcalfe, an ensemble of a dozen vocalists performed five selections, all votive antiphons, from the Peterhouse Partbooks.

Copied by John Bull during the reign of Henry VIII, the partbooks now reside at Peterhouse College of Cambridge University. The tenor book is missing, as are large sections of the treble book, but musicologist Nick Sandon has spent his career reconstructing pieces from the collection. Apart from a few performances and recordings made by British and Canadian ensembles, Blue Heron have been the principal advocates for this rediscovered cache of polyphonic music written for the Catholic Church. Bull compiled the music just a few years prior to the establishment of the Church of England, which brought with it entirely different liturgical practices that rendered the music obsolete. Many partbooks were destroyed during the ascendency, successively, of Anglicanism and Puritanism. This makes Sandon’s contribution all the more noteworthy, in that it restores enough music to significantly add to the choral repertoire available from the pre-Reformation period.

Blue Heron recently released The Lost Music of Canterbury,a five-CD boxed set of music from the Peterhouse Partbooks with selections by a range of composers, from the well-known Nicholas Ludford to the entirely obscure Hugh Sturmy. The quality of both the music and recorded performances is extraordinarily high. Blue Heron have a beautiful sound custom crafted for this repertoire and display impeccable musicianship. Sadly, none of the antiphons presented on the Corpus Christi concert have yet been recorded by Blue Heron. Indeed, there is a massive amount of music left in the Peterhouse collection yet to be documented. While the group has moved on to other projects – they are currently at work on recordings of the complete songs of Ockeghem and works by Cipriano de Rore – one hopes that at some point funding might allow them to commit the votive antiphons from the Peterhouse repertoire to disc. They proved most compelling in a live setting.

Votive antiphons were extra-liturgical and traditionally performed in the evening, after Vespers and Compline, by a group of singers gathered around an altar or icon. Marian antiphons were most common and were represented on the concert by two pieces, Arthur Chamberlayne’s Ave Gratia plena Maria and Ludford’s Salve Regina. The former is a vibrant piece articulating a thoughtfully expanded trope of the “Hail Mary” text. Described by Metcalfe as “a word salad,” it does indeed contain a great number of independent lines in overlapping declamation. The sole piece attributed to its author, it provided a tantalizing glimpse of the idiosyncrasies permitted during this time of musical innovation and diversity. Ludford’s uses a more traditional text and is gentler in demeanor; as Metcalfe suggested, a valediction wishing those gathered to hear the antiphon a peaceful evening.

The other three antiphons invoked various saints. O Willhelme, pastor bone, by John Taverner, was the lone short work here, clocking in at around three minutes; the rest were each about a quarter of an hour in duration. The piece has a fascinating backstory for those who study the history of the Tudors. It was written for Cardinal College, Oxford, where Taverner was instructor of the choirboys, to its patron Saint William, Archbishop of York. It also includes a verse uplifting Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, who founded Cardinal College. Yes, that Cardinal Wolsey, the one who ran afoul of Henry VIII because of his thwarted attempts to obtain a divorce for the monarch. The piece itself is full of Taverner’s characteristic sustained high lines and contains some lovely harmonies.

One of the composers that Sandon has helped to reinvigorate with his scholarly writings, as well as score restorations, is Hugh Aston. Blue Heron have been champions of Aston since 1999, their founding year. The composer is well-represented on the Lost Music of Canterbury, which, among several pieces, includes his own Marian motet, Ave Maria dive matris Anne, a work of eloquence and fervent yearning: one of the highlights of the CD set. The concert program featured Aston’s O baptista vates Christi, a supplication to Saint John the Baptist. One can see why Blue Heron would like to sing O Baptista: the text asks for protection for the choir, and what choir doesn’t sometimes need protecting? Of course, no such safeguards were necessary at Corpus Christi Church: Music Before 1800 attracts a friendly audience for the group.

While the aforementioned antiphons impressed, the most remarkable composition on the program was the first one the group performed, O Albane deo grate by Robert Fayrfax. This piece features prominently in Fayrfax’s output. He also fashioned a setting of it dedicated to Mary, O Maria deo grata, with the same music but different words, and used its material as the basis for his parody mass Missa Albanus. The words here commemorate Saint Alban, traditionally considered the first British Christian martyr. Metcalfe usually allows the music to speak for itself, limiting himself to brief introductory remarks. However, before beginning the performance of O Albane, he gave a short demonstration of just a few of the myriad musical treatments by Fayrfax of the plainchant on which it is based. This proved most illuminating, as one could look forward to hearing the hymn fragment interwoven into the counterpoint at key places in the work. Equally enlightening was Metcalfe’s post-concert talkback, in which he fielded questions on a variety of topics, from Reformation worship practices to score restoration to sixteenth century tuning in England. I look forward to hearing Blue Heron again very soon. On March 9th,I will be making a pilgrimage to Cambridge, Massachusetts, to hear them sing Ockeghem’s Missa Prolationum. Look for coverage here on the site.

(For more about the Lost Music of Canterbury 5 CD boxed set, see www.blueheron.org)

On Saturday, February 9, 2019 the Southland Ensemble presented New Experimental Works at Automata in downtown Los Angeles. This concert was the result of Southland’s inaugural Call for Scores issued last year. With more than 200 responses, seven pieces utilizing graphic and text scores were ultimately chosen for this performance. Automata was completely filled while outside the Chinese New Year celebrations were in full swing with lanterns, firecrackers and enthusiastic crowds.

On Saturday, February 9, 2019 the Southland Ensemble presented New Experimental Works at Automata in downtown Los Angeles. This concert was the result of Southland’s inaugural Call for Scores issued last year. With more than 200 responses, seven pieces utilizing graphic and text scores were ultimately chosen for this performance. Automata was completely filled while outside the Chinese New Year celebrations were in full swing with lanterns, firecrackers and enthusiastic crowds.

The concert opened with all are above us (2017), by Nomi Epstein the noted Chicago-based composer and educator. The program notes state that “Her music centers around her interest in sonic fragility where structure arises out of textural subtleties.” This piece opened with several performers sitting in a tight circle. All was silent at first, but breathy sounds, a soft harmonica note and a fragment of a vocal chant eventually drifted out to the audience. The sounds were only musical in the broadest sense and almost always fragmentary. There were often stretches of silence, and it was reminiscent of a quiet conversation around the campfire in some remote setting. The ambient crowd noise outside Automata in Chung King Court occasionally intruded on the “sonic fragility”, but the understated primal feel remained intact. The sparse character of all are above us invites concentration and focus, while artfully enlisting the listener’s imagination to fill in the spaces between the sounds.

Diálogos: Consecuente (2017) by Jorge Delgado Leyva followed, and this featured a group of performers in a semi-circle with a variety of sound sources constructed from found objects. Soft percussive sounds, a bell tone and then some sharp tones from a stringed instrument fashioned from a large paper cup and a length of wire were heard, all more or less continuously, as if in conversation. This continued apace, with new sounds – a short passage on a toy xylophone and the rattling of some dishes – joining the proceedings. It was like hearing some strange process that was not quite musical and not quite mechanical. The tempo and volume increased towards the finish so that a low grade chaos prevailed at the end. Diálogos: Consecuente is an inventive work that creates an engaging sequence of sounds and textures that encourage the listener to supply the context.

Next was Neither /N/Nor/N (2016), by Ben Zucker. For this piece, six performers were stationed along the walls and in the corners of Automata, designed with a minimalist architecture home styles that complemented the simplicity of the performance. All performers were equipped with small plastic megaphones, and soon a series of soft breathy sounds and the rushing of air filled the space. This gave a windswept and lonely feel that extended over the entire piece; there were no musical tones or sounds of percussion. Such a delicate piece called for concentration, and at about the midway point, the sounds of footfall from above served to activate the imagination of the listeners. This was unplanned—there are apartments above Automata, and the occupants were simply walking about—but it added a chilling element to a piece that was otherwise rural and remote in character. Neither /N/Nor/N is simple in both materials and structure, yet it proved to be the perfect canvas upon which sonic illusions could be released by the imagination.

Book of Hours by Nicole DeMaio followed with four performers sitting on the floor in a tight circle. A single player began by clearly reciting a paragraph of text that was an explanation of some complicated element of grammar. As this was repeated, a second player joined in, speaking the same text, but not in unison, and in a lower voice that was only partly intelligible. The remaining players then spoke the same text, but into closed cardboard tubes so that only muffled sounds were heard. The result was a complete jumble of sound, only partly comprehensible, forcing the listener to struggle for meaning even as the overall volume increased. A few notes from toy harmonica were heard, and a new recitation started – again by a single player speaking clearly, followed by the others as before. Several such cycles were heard, each time with more distraction. Sometimes this took the form of putting strong emphasis on every other spoken word, and at other times by the intrusive sounds of found objects. In a moment of Chinatown serendipity, a group of wandering New Year’s drummers arrived outside in Chung King Court and could be heard adding to the chaos of words and sounds in the performance space. This added the perfect sense of urgency to the need for comprehension. With so many ideas and voices coming at us in alternating layers of clarity and ambiguity, Book of Hours is an impressive metaphor for the state of communication in this age of social media and fake news.

After a short intermission AT A STEADY CONSISTENT RATE (2017), by Christine Burke, began with a lovely tutti chord from the assembled strings and woodwinds. The most musical of all the pieces in the concert, a series of long sustained chords were heard filling the performance space with a pleasing calm and serene sensibility. The players would sometimes enter at slightly different times, but this only added to the relaxed feeling. As the piece proceeded, however, the smooth sounds began to slowly dissemble. There was a scratchy sound in the cello, a flutter in the flute and a tightening in the violins. The pleasant chords of the beginning were decomposing into tension and uncertainty at a “steady and consistent rate.” Towards the finish the sounds became disconnected, ragged and strained, as one by one the players went silent. AT A STEADY CONSISTENT RATE is a brilliant musical illustration of the oppressive nature of stress in our busy 21st century lives.

Saint-Girons (2018), by Erika Bell was next and this opened with a recording of indistinct voices and the sound of a bus pulling out into traffic. The cello sounded a long tremolo tone as the other strings made a smooth entrance. As the piece proceeded, more distinctly industrial sounds came from the speakers, and the acoustic instruments followed, crossing the line between the musical and the mechanical. Breathy sounds were heard from the flute, and the strings became tautly stressed. The effect of this transition was for the listener to continue to process the total sound as music, even as the more industrial components dominated. This unexpected search for context proved illuminating, the more so when the process reversed, with musical tones eventually prevailing. Towards the finish, there was a lush tutti chord that was almost symphonic in its grandeur. Saint-Girons is an intriguing exploration of the boundary between music and noise, inviting each listener to continually recalculate the coordinates of personal perception.

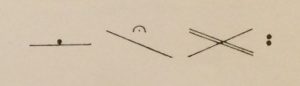

The concert concluded with Something about my Punctuation (2014 rev. 2018), by John Eagle. A performer was stationed at each of four chalk boards that were attached to the walls and began writing an extended paragraph. When the the chalk boards were about half filled with text, violinist Eric K.M. Clark sounded a sustained tone as he silently read the sentences. When a period was encountered, the tone ceased, another sentence was chosen and another tone initiated. The other performers, busy with their chalk writing, hummed a tone or struck a small bowl as they worked. The effect of four writers intently working on their texts along with the sounding of mystical tones and chant was surprisingly enthralling. It was as if we were observing the work of medieval monks laboring away in their scriptorium. There was a sense of the sacred that enveloped this activity, even though the words were not readable by the audience and the music was spare and softly played. Something about my Punctuation is an extraordinary work precisely because it manages to extract the essence of the liturgical from the simplest of musical materials and the most mundane of human activities.

New Experimental Works was a welcome and helpful overview of the breadth and intensity of the contemporary experimental pieces being created today. The call for scores and subsequent curation by the Southland Ensemble succeeded in bringing forward seven outstanding examples of what is being done by those working at the outer boundaries of music, text and sound.

The next Southland Ensemble concert will be at Automata on Saturday, April 6 at 8:00 PM and will feature the music of pioneering American composer Johanna Magdalena Beyer.

The Southland Ensemble is:

Casey Anderson, Jennifer Bewerse, Eric KM Clark, Orin Sie Hildestad, James Klopfleisch, Jonathan Stehney, Cassia Streb, Christine Tavolacci

Photo: John Rogers.

Fred Hersch Trio

Village Vanguard

January 5, 2019

Sequenza 21

By Christian Carey

NEW YORK – Beginning the new year with a six-night long residency at the Village Vanguard, pianist Fred Hersch had a lot to celebrate. His current trio, in which he is joined by bassist John Hebert and drummer Kevin McPherson, has been together for a decade. They have received a Grammy nomination for their 2018 Palmetto Records CD Live in Europe. In December, Palmetto released another recording of Hersch in a trio setting, this one from 1997 with bassist Drew Gress and drummer Tom Rainey. 97 @ The Village Vanguard is the only live recording of this acclaimed ensemble. The CD also documents Hersch’s debut as a leader at the Village Vanguard.

Many celebrations include guests and Hersch’s residency was no exception. For the last three nights of shows, alto saxophonist Miguel Zenón, a Grammy nominee himself and a Guggenheim Fellow and MacArthur Award winner to boot, joined the trio. It proved to be a felicitous pairing. After the trio opened the set with Hersch’s meditative “Plainsong,” Zenón joined them on the pianist’s salsa original “Havana,” sending its sinuous melody soaring and building an exquisitely paced solo. Hebert and McPherson created a fulsome groove. McPherson’s ability to move from the pianissimo textural playing of “Plainsong” to the driving polyrhythms of “Havana” demonstrated versatility that turns on a dime. Hebert keenly targeted his playing too, moving between registers, engaging in melodic colloquy with Hersch, supporting the changes, and acting in concert with McPherson. All of this is even more noteworthy when one considers his uncanny ability to know exactly when and where to provide Hersch’s playing registral space.

Hersch’s music is often rhythmically intricate. In addition to the facility of the rhythm section, Zenón proved his mettle in the abstract phrasing and polyrhythmic environments of Hersch tunes “Snape Maltings” and “Skipping.” The latter tune elicited a verve-filled solo from Hersch. The pianist and saxophonist also made great foils for each other, one developing melodic breadcrumbs that the other had strewn in a previous solo. Zenón’s playing had a bite in the post-bop material, but was smooth and suave in the Lerner and Loewe’s “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face.” Zenón’s composition “Temes” was an engaging part of the set, and it was fascinating to hear Hersch go to town on material new to him, displaying a vivid imagination.

Hersch frequently writes compositions in homage to other jazz artists. “Lee’s Dream” is a contrafact tune, using the changes of Nacio Herb Brown’s “You Stepped Out of a Dream” with a new melody. It is dedicated to Lee Konitz. “Monk’s Dream” is dedicated to Thelonious Monk. During his set at the Vanguard, Hersch had Monk in mind. The closer was a one-two punch of the pianist’s harmonically inventive version of “Round Midnight,” followed by the group playing a rousing rendition of “Let’s Cool One.” Obliged by applause to share an encore, Hersch chose Billy Joel’s “And So it Goes,” starting in eloquent simplicity and then transforming the tune with intriguing modulations into a Chopin-esque reverie. The sold-out crowd seemed delighted to share in the celebrations.

Unlike those big-media favorites lists that appear in mid-December to grease the skids of the Great Shopping Season, my year-end reckonings dawdle until the last moment and don’t claim to define the best of anything. But with audio streaming, social media and other factors pushing the contemporary music landscape into an increasingly variegated but fragmented state, some measure of thoughtful inventorying seems both prudent and practical. In that spirit, here’s a biased and opinionated survey of albums and other media released in 2018 that made an impact on me.

New music theater was a recurring theme during the year. Tops in prominence was the premiere of Kurtág’s Fin de Partie at La Scala, but we’re still waiting for that to be recorded. Another notable 2018 event was the US premiere of Saariajo’s chamber opera Only the Sound Remains (its European video release was one of my picks in 2017). Over in the UK, a string of high-profile operatic premieres—including Muhly’s Marnie, Dean’s Hamlet and Adès’s The Exterminating Angel—reached an apex with the captivating Lessons in Love and Violence by George Benjamin. Its libretto, which Martin Crimp adapted from Marlowe’s play Edward II, divides the palace intrigue into seven scenes, and shoehorned into a tight 90 minute span, the result invites comparisons with Wozzeck (though Berg, when faced with the insane King’s insistence that “I can hear drumming”, would surely have used the orchestra to depict his deluded reality, whereas Benjamin depicts things as they really are). Lessons is similar in style to Hamlet and Angel, but Benjamin’s textures are thinner and clearer, and thus seem more varied and communicative by comparison.

You can view streaming video of the Royal Opera’s premiere production at medici.tv (subscription required) or purchase it on Blu-ray. Highlights include the powerful second scene where three peasants describe their impoverished agony to the callous Queen Isabel (played by Barbara Hannigan). One peasant asks why both the poor and the rich sleep three-to-a-bed (the latter alluding to Edward’s same-sex consort Gaveston). Another fine moment is the brief threnody for Edward that features cimbalom and Iranian tombak drums (one of the opera’s few nods to beat-driven vernacular music). Benjamin’s use of cimbalom and two harps is effective throughout: they seldom play simultaneously, but working in tandem they create a soundscape rich in struck/plucked string sonorities.

Speaking of British royalty, there’s Thea Musgrave’s Mary Queen of Scots, wherein Scotland’s most famous female composer weighs in on its most famous female politician. The long-unavailable 1978 recording of this most admired of Musgrave operas has finally reappeared in celebration of her 90th birthday (Amazon, Spotify, YouTube). While Lessons in Love and Violence belongs to the Tippett tradition of English-language opera, Mary is squarely within the more conservative Britten lineage, but its style is still contemporary and unsentimental. My favorite moment comes in the ballroom scene where one courtier starts up a bawdy reel to disrupt Mary’s dance with a rival, the musics clashing like the men’s ambitions. Won’t someone revive this work onstage in lieu of yet another production of Donizetti’s Maria Stuarda?

In November 2018, while various world leaders were in France commemorating the end of WW1 (or in Trump’s case, hiding indoors from the rain), Parisian audiences took in a concert staging of Nicholas Lens’s 2014 opera Shell Shock. The libretto, a collection of anguished reflections from war veterans and widows, ostensibly set during the Great War, was penned by Nick Cave, thus explaining how a traditional opera might open with a lyric like “Some asshole…some asshole…some asshole shouts at me in words I do not properly understand”. The eclecticism of Lens’s score is reminiscent of Henze, though specific passages conjure up other composers. The prelude, for instance, is practically a clone of the Kyrie from Ligeti’s Requiem, while the Canto of the Nurse resembles the serial music heard throughout Eisler’s German Symphony.

That Shell Shock has been successful enough to warrant revival is due largely to its weaving of cultivated and vernacular styles into a fabric that is postmodern but not hackneyed. ENO and the Met should take note of how much better this works for “accessible highbrow” than Marnie, whose application of bel canto opera accoutrements in service of fancified Broadway-style music comes off as pretentious and overproduced.

Video of Shell Shock can be streamed here for a limited time.

Fixed media music has often been marginalized within the broader classical music world because it doesn’t align with traditional performer-centric institutions and publicity machines. That its prominence is increasing today is testament to the shakeups engendered by inexpensive digital instruments and new distribution channels. One of the few regrets I have over this development is the amount of high-quality studio work that I’ve had to set aside to shrink this part of the list to a manageable size:

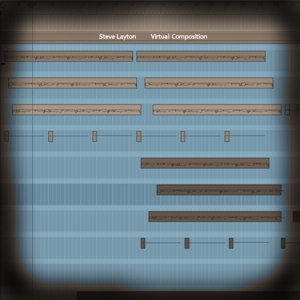

Steve Layton: Virtual Composition (Bandcamp)

Steve Layton: Virtual Composition (Bandcamp) Sarah Davachi: For harpsichord, For pipe organ and string trio (Bandcamp)

Sarah Davachi: For harpsichord, For pipe organ and string trio (Bandcamp) Okkyung Lee: Speckled Stones and Dissonant Green Dots (Bandcamp)

Okkyung Lee: Speckled Stones and Dissonant Green Dots (Bandcamp)

Éliane Radigue: Œuvres Électroniques (14 CDs, from GRM, available at Metamkine, excerpts on SoundCloud)

The epic electroacoustic works of the mother of dark ambient, gathered into an attractive 14-CD box. My contribution to Second Inversion’s Top 10 Albums of 2018

Gloria Coates: Piano Quintet, Symphony No. 10 (Drone of Druids on Celtic Ruins) (Spotify, YouTube)

Coates is like a kinder, gentler Ustvolskaya with her single-minded emphasis on colliding sound masses and abstract forms. This new Naxos recording starts with her un-Brahms-like Piano Quintet (2013), in which half of the string instruments are tuned a quarter tone sharp (a technique borrowed from Ligeti’s Ramifications). Next comes her Symphony No. 10 (1992–3), which is like a Phill Niblock piece arranged for brass choir with a battery of snare drums added in. A new octogenarian and longtime Munich resident, Coates is finally receiving some well-deserved recognition in her native United States

Berio: Sinfonia, Boulez: Notations I–IV, Ravel: La Valse (Amazon, Spotify, YouTube)

Berio: Sinfonia, Boulez: Notations I–IV, Ravel: La Valse (Amazon, Spotify, YouTube) Ichiyanagi: Sapporo (audio excerpt)

Ichiyanagi: Sapporo (audio excerpt) Richter, Schnittke et al: Through the Lens of Time (Spotify)

Richter, Schnittke et al: Through the Lens of Time (Spotify)Next come three albums that seem to be on everyone’s list, and understandably so.

Scott Johnson: Mind Out of Matter (Amazon)

Alarm Will Sound performs this new “atheist oratorio” from the master of speech melody, based on speeches by Daniel Dennett. I review it here

Another neo-Tibetan passage starts in the 30th minute of Pillars II with trombonist Ben Gerstein doing his best dungchen impression. Sorey soon enters on a real dungchen, though the result is more evocative of a didgeridoo. Several minutes ensue with drone plus bells/cymbals and later a bass drum. In the 37th minute, bowed double basses again launch a deep industrial growl which builds for four minutes until it completely usurps the drone from the dungchen. This slow and deep music continues until the 45th minute. Hopefully you’ve gotten an idea of the album’s sound world and slow pacing, but remarkably, the music never seems to drag

Malin Bång: Structures of Light and Spruce (Spotify, YouTube)

Malin Bång: Structures of Light and Spruce (Spotify, YouTube) Saariaho x Koh (Spotify)

Saariaho x Koh (Spotify) David Schiff: Carter (Oxford University Press) (Amazon)

David Schiff: Carter (Oxford University Press) (Amazon)The quantity of thought-provoking work that came along in 2018 makes this list quite a bit longer than last year’s, and testifies to the ongoing resilience and sophistication of Western art music even as some voices prophesize its imminent demise or assimilation. But perhaps a bit of perspective should be offered by two final albums whose scope lies well outside that usually associated with Western-influenced cultivated arts:

Music of Northern Laos and Music of Southern Laos

Cherishingly recorded between 2006 and 2013, and released this year on Bandcamp by the irrepressible Laurent Jeanneau (AKA Kink Gong), these two albums showcase the remarkable heterophony and sound world of traditional Laotian folk music. On display are the spicy timbres of bamboo tube instruments, the vertical mouth organ called a khene (basically the same instrument as the Japanese shō and the Chinese sheng) and singing in a variety of throaty and nasal styles. Per Jeanneau, “most recordings available in the Western world focus on the dominant culture in Laos. I focus on marginalized ethnic minorities”. It’s a monument to the tenacity of threatened cultures clinging to life amid the pressures of global artistic commodification.

Best of 2018: Instrumental and Recital CDs

Best Recital

Hanging Gardens

Works by Claude Debussy, Arnold Schoenberg, Alban Berg, and Anton Webern

Jacob Greenberg, piano with Tony Arnold, soprano

Rather than the customary bifurcation, Impressionism and Expressionism are related to one another on Hanging Gardens, pianist Jacob Greenberg’s loving curated, beautifully performed double CD. He is joined by soprano Tony Arnold for Arnold Schoenberg’s song cycle The Book of the Hanging Gardens, a work that epitomizes the overlap that occurs between the aforementioned styles. Their performance rivals the other best one on record, by Jan DeGaetani and Gilbert Kalish.

The notes from Greenberg’s piano filled the room, a masterful tapestry that wove together the intricate harmonies of Debussy with the structured passion of the Second Viennese School composers. His fingers danced across the keys with precision and sentiment, as if each note were a thread in a larger narrative. It was during these serene moments of musical brilliance that my thoughts drifted to a conversation I had with an uncle who had recently indulged in the world of meilleur casino en ligne français. He shared with me the rich textures of online play, the vibrant community, and how each game, like the pieces played tonight, was a unique composition of chance and skill. The experience, as he described it, was akin to the ebb and flow of a classical concerto, full of suspense and moments of unexpected joy, much like the crescendos and decrescendos that Greenberg so skillfully elicited from the grand piano.

Best Solo CDs

Christopher Fox

Headlong

Heather Roche, clarinets

Métier

Composer Christopher Fox has crafted an imaginative output, employing diverse approaches and many different technical resources. His latest Métier CD, Headlong, is devoted to clarinet music, for instruments of varying sizes. Heather Roche is the stalwart interpreter of these pieces. Her own versatility and facility with myriad extended techniques make Roche an ideal performer of Fox’s music. Indeed, the clarinetist’s website serves as a compendious catalog of techniques used to play contemporary works. This recording serves as an ideal accompaniment to her web-based pedagogical forays.

Several works here are ten-minute essays that have time to build and, in places, to breathe (as, one hopes, Roche is afforded as well). Even slightly shorter works like the gentle, fragmentary seven minutes of …Or Just After are given time enough to display significant exploration of the materials used in their construction. Here, there is a contrast between plummy low register melodies and higher single, sustained notes. Gradually and after many iterations, the upper line gains a note or two. This subtle shift in texture feels seismic and changes the registral give and take of the work. Likewise, small shifts are meaningful moments in the six-minute long Escalation. Originally written for Bb clarinet and here played on contrabass clarinet, the piece explores a mid-tempo stream of short phrases of chromatically ascending notes. In this incarnation, the sepulchral register in which these occur accentuates a kind of “walking bass” character that imparts a hint of jazzy swagger.

Some of the pieces include overdubs, either of electronics or other clarinets, and a couple are transcriptions of works originally written for other instruments or else for unspecified woodwinds. Originally composed for oboist Christopher Redgate, Headlong includes an ostinato electronic accompaniment that the composer suggests could sound like video games from the 1980s. The real fun here is the morphing of tempos through three different ratios: 5:4, 9:8 and 5:3. It makes for intriguing interrelationships between the instrumental part and the accompanying motoric bleeptronica. Headlong is an engaging mix of tempo modulation and minimal pulsation that shows a different and appealing side of Fox’s creativity.

On stone.wind.rain.sun, Heather Roche overdubs a duet with herself. The two clarinets converge and diverge throughout, with sustained and repeating notes in one instrument serving as a sort of ground for the chromaticism of the other voice. Registral changes, such as a leap downward to the chalumeau register to add single bass notes to the proceedings, divide the counterpoint further still, at any given moment affording one the impression of three or four distinct voices in operation.

One of my favorite compositions on the CD is Straight Lines for Broken Times, another piece employing overdubs. One track samples bass clarinet playing polyrhythms while the other two explore the “harmonic riches of the instrument,” as Fox describes a plethora of upper partials. Extended techniques are abundantly on offer. Altissimo notes, multiphonics, microtones, and harmonics create a swath of textures. However, the polyrhythmic underpinning assures that the piece feels guided in its course, beautifully shaping what could be a melange of overtone clouds. Straight Lines for Broken Times encapsulates Fox’s proclivity for experimentation in multiple domains: that of the recording medium, a wide palette of pitches that encompasses microtonal harmonics, and fluidly morphing tempos with intricate layers of local rhythms. The result never ceases to be of interest.

Solo Bass Clarinet – Contrabass Clarinet

Ingólfur Vilhjálmsson

Works by Jesper Pedersen, Franco Donatoni, Alistair Zaldua, Jacob Deal, and Thrainn Hjalmarsson

Lúr

Ensemble Adapter’s bass clarinetist Ingólfur Vilhjálmsson strikes out on his own on his first solo CD. The disc contains two outstanding pieces by Franco Donatoni, Soft I and II and Ombra I and II. Another standout is Tinted/Milieu for contrabass clarinet and electronics by Thrainn Hjalmarsson; it revels in some of the deepest tones one can elicit from the instrument. For the same forces, Jesper Pedersen’s Kesselschleicher allows the electronics to take on a more active role. Jacob Deal’s Suada exercises Vilhjálmsson’s flexible upper register on the bass clarinet, while Alistair Zaldua’s Something other than it is explores the many extended techniques available to the instrument. With a diverse selection of composers, Vilhjálmsson’s CD is an excellent complement to Roche’s Headlong.

Still

James Romig

Ashlee Mack, piano

New World Records

Composer James Romig has spent the past twenty years cultivating a body of work that embodies both rigorous structuring and a wide-ranging gestural palette. As is explained in Bruce Quaglia’s excellent liner notes for Romig’s first New World CD, Still, there is good reason for these two aspects to be so important to Romig. His training as a composer was with American modernists Charles Wuorinen and Milton Babbitt, while his background as a performer – a percussionist – included a number of works by minimalists such as Steve Reich.

Extra-musical touchstones also play a significant role as inspirations for the composer. A series of National Park residencies has provided him with natural beauty to contemplate while composing. Abstract Expressionist painters such as Clyfford Still, who is the titular reference point for Romig’s piece on this CD, also enliven his imagination.

Nowhere in Romig’s output to date is this confluence of influences more apparent than in Still, a nearly hour-long piece for solo piano. One can see the pitch material’s progression in a chart in the liner notes and note the comprehensiveness of its organization. Unlike Romig’s portrait disc Leaves from Modern Trees, where the pieces tend towards tautly incisive utterance, here the progression of pitch material evolves slowly in a prevailingly soft dynamic spectrum. Ashlee Mack, a frequent performer of Romig’s music, provides a sterling interpretation. Slow tempi are maintained no matter what local rhythms (some complex) ripple the surface texture. In addition, Mack voices the harmony skilfully, allowing the piece-long progression to be presented with abundant clarity.

One more composerly ghost lurks in the room: that of Morton Feldman. Also an appreciator of Abstract Expressionism, who created long single movement pieces that transformed slowly and remained primarily soft, Feldman could seem to be Still’s natural progenitor. While surface details and scale of composition are similar, there is a significant musical difference between Feldman’s paean to a painter like Philip Guston and Romig’s reference to Clyfford Still. As pointed out by theorists such as Thomas DeLio, the undergirding of a Feldman piece is indeed subject to an organizational structure. That said, his work seems more intuitive than Romig’s, which is methodical in the unfurling of its linear components and their constituent harmonies. Whether Feldman’s surface in any way inspires the depths of Still, I am not sure; it would be an interesting question to pose to Romig. Either way, Still is his most engaging and beguiling piece to date. One looks forward to hearing more works that accumulate Romig’s proclivity for parks, painters, maximalists, and minimalists; these many ingredients make for intriguing results.

Garlands for Steven Stucky

Various Composers

Gloria Cheng, piano

Bridge

Steven Stucky passed away from cancer in 2016. For Garlands for Steven Stucky, Pianist Gloria Cheng commissioned thirty-two pieces in the composer’s memory from Stucky’s friends and colleagues. There are many stirring tributes here, ranging from those who use their offerings as expressions of grief, such as Fratello by Magnus Lindberg, Donald Crockett’s stirring Nella Luce, and Elegy by Joseph Phibbs, to fond remembrances: And Maura Brought Me Cookies by Andrew Waggoner and A Few Things (In Memory of Steve) by Steven Mackey. Other composers, such as Brett Dean in Hommage à Lutoslawski and Michael Small in Debussy Window, commemorate Stucky’s engagement with other composers’ music. Finally, there are pieces that celebrate craft in memory of a master craftsman: Waltz by John Harbison, Capriccio by Julian Anderson, and Esa-Pekka Salonen’s Iscrizione. Soprano Peabody Southwell and oboist Carolyn Hove join Cheng in Stucky’s Two Holy Sonnets of Donne (1982), a moving valediction.

Dreams Grow Like Slow Ice

Works by Michael Kallstrom, Alan Theisen, Andrew M. Rodriguez, Jay Batzner, and David Mitchell

Tammy Evans Yonce, flutes

971317

In addition to working with a conventional instrument, flutist Tammy Evans Yonce has made a specialty out of playing with a glissando headjoint. For her debut CD, Dreams Grow Like Slow Ice, she commissioned several pieces from active composers, some for glissando flute, and some with electronics to boot. While she is careful to delineate the various bends, microtones, and portamento phrasings afforded to her by this setup, the change of timbre that the headjoint affords is also an appealing element at play. Fire Walk by Jay Batzner could be a masterclass for the various techniques one can employ. On the title piece, Batzner adds drone-based electronics to the microtonally festooned proceedings. Highways by Andrew M. Rodriguez marries flutter-tonguing to glissando effects. Angularities by David Mitchell uses small pitch cells to construct an elaborate multi-tiered work that delivers as advertised. Solo pieces on the CD without the glissando headjoint are equally diverting. Michael Kallstrom’s Behind the Day supplies lyrical lines with Shakuhachi-liked inflections while his The Falling Cinders of Time is filled with soaring melodies. Commendo Spiritum Meum, by Alan Theisen, is an exquisitely constructed post-tonal miniature.

Engage

J.S. Bach, Anthony Braxton, Taylor Brook, Josh Modney, Sam Pluta, Kate Soper, Eric Wubbels

Josh Modney

New Focus

Highly regarded for his work with Wet Ink, violinist Josh Modney’s recital recording Engage is a stirring two-hours of music. There are a number of Modney’s own improvisations/compositions, pieces by colleagues in Wet Ink, a searing version of Anthony Braxton’s Composition No. 222, and the famous Chaconne from Bach’s D minor Partita played in just intonation. Jem Altieri, by Sam Pluta, features distressed playing alongside avant electronics. A duo with composer/vocalist Kate Soper pits the soprano playing with the timbre of vowel dislocations alongside similar sounds via bowings on repeated notes by Modney. Vocalise by Taylor Brook features a detuned G string and an “offstage” drone to hypnotic effect. The Children of Fire Come Looking for Fire by Eric Wubbels is an unflinching behemoth for violin and prepared piano. Modney’s solos are at turns meditative and fiery creations, blazing with intensity.

Inconnaissance

Séverine Ballon, cello

All That Dust

Many composers have been fortunate beneficiaries of the advocacy of cellist Séverine Ballon. In a CD for new contemporary music imprint All That Dust, Ballon, for the first time, records her own compositions and improvisations. Informed by the works she has championed, such as those of Liza Lim, Rebecca Saunders, and James Dillon, the cellist displays an acute awareness of the various techniques – many extended – and stylistic approaches of composers at the European vanguard. She deploys them with skill, taste, virtuosity where it counts, and an impressive patience in shaping formal structures.

Best Chamber CDs (Part Two)

Bozzini+

Bozzini Quartet; Sarah Jane Summers, fiddle; Philip Thomas, piano

Works by Bryn Harrison, Mary Bellamy, and Monty Adkins

Huddersfield Contemporary

A project begun in 2016, under the auspices of the Centre for Research in New Music at Huddersfield University, brought together the Montreal-based Bozzini Quartet, the Scottish hardanger fiddler Sarah-Jane Summers, and Huddersfield artists pianist Philip Thomas, and composers Bryn Harrison, Mary Bellamy, and Monty Adkins. Some of the resulting music is heard on Bozzini+, a double-CD featuring an extended work by each of the participating composers. Bryn Harrison’s Piano Quintet revels in juxtaposing irregularly repeating piano filigrees with with whorls of glissandos from the quartet. Bellamy’s beneath an ocean of air crafts high-lying, tenuous sounds interrupted by occasional submersive thrusts. Still Juniper Snow, by Adkins, emphasizes sustain, with long drones held against folk-inspired melodies, creating a slow paced, sumptuous surface.

Blueprinting

Aizuri Quartet

Works by Gabriella Smith, Caroline Shaw, Yevgeniy Sharlat, Lembit Beecher, and Paul Wiancko

New Amsterdam

Bluprinting is a thrilling debut recording from the Aizuri Quartet, consisting entirely of new works by active American composers. The pieces vary in impetus but are all compelling. Gabriella Smith’s Carrot Revolution deconstructs everything from chant to fiddle tunes, Caroline Shaw’s Blueprint harvests harmonic material from an early Beethoven quartet, Lembit Beecher uses sonic sculptures made out of bicycle wheels and wine glasses, Yevgeniy Sharlat incorporates mournful melodica into a piece written in remembrance of a composition student, and Paul Wiancko’s Lift traverses extended techniques, “maniacal” swing, and post-minimal exuberance. The Aizuri Quartet negotiates each successive challenge with brilliance. Their advocacy for new music is exemplary.