It’s tough to say goodbye forever to Woody Vasulka, pioneer of experimental video and co-founder (with his widow Steina) of The Kitchen in New York. It was his 40-minute “video opera” The Commission that was the most formative work of video art that I’ve ever encountered. Reflecting on his career in these days since his December 20 passing, my thoughts keep returning to the stupefying effect of experiencing that piece for the first time, a memory that remains visceral for me decades later.

It was in the early 1980s. Following a conventional musical apprenticeship in Southern California, I’d enrolled as a composition major at USC, where Robert Moore, the professor who ultimately had the most influence on my intellectual development, encouraged me to read Gene Youngblood’s 1970 classic Expanded Cinema, which introduced me to the mind-blowing world of experimental cinema. I began attending Terry Cannon’s screenings at Pasadena Filmforum, where I became acquainted with the 16mm work of Stan Brakhage, the Whitney Brothers, James Broughton, Sharon Couzin, Gunvor Nelson, Bruce Elder and a few local filmmakers. But my direct experience with the video side of experimental cinema was still limited to figures like Nam June Paik who were closely associated with contemporary music.

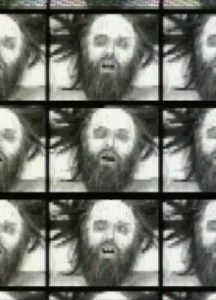

In 1983, looking to get better acquainted with that newest of artforms, I ventured to a screening at Modern Visual Communications, a boutique venue founded by Richard Kennedy that had a brief but fabled run just off Melrose Avenue. The program was devoted to the Vasulkas—Woody the Czech and Steina the Icelandic—artists who, working both individually and in concert, had attained an eminence in avant-garde video comparable to that of Brakhage in film. The impression of their high-contrast imagery, often produced using custom image processing equipment, was maximized by the gigantic bright CRT display in the screening room—a luminescent gun firing the tableau directly at the spectators’ retinas with an impact similar to the aural assault of a loud rock concert. Today’s video projectors and solid-state displays, which tend to soften and flatten moving images, don’t do justice to such vintage analog-era video works. The evening opened with Woody’s Progeny (1981), then traversed a couple of single-channel shorts by Steina, before heading into the main event: the local premiere of Woody’s newest piece, The Commission.

As a composer, I appreciated the music history themes in the work, which loosely treats the Paganini-Berlioz relationship at the time of Harold in Italy‘s inception. The extensive use of image processing created a kind of surreality that presented a welcome alternative to the desensitizing simulationism of commercial television. And the harmonized pitch shifting applied to the spoken dialogue, combined with the strategic deployment of abstract electronic music at key moments, created original pitch structures that actually worked musically. Woody cast the lanky intermedia artist Ernest Gusella as Paganini, portraying him as a tormented artist who could barely speak and who is eventually subjected to an Italian-language autopsy in a rescan scene whose debeamed imagery symbolizes his moribund physical essence. In contrast, Robert Ashley’s Berlioz is a suit and safari hat bedecked capitalist foil (“I consider myself very much a company man”). It remains the most compelling use of the Ashley persona that I’ve ever seen (his stylized drawl always seemed to work better when someone else was directing him, whereas his own self-centric pieces too often slid into narcissism). Both Gusella and Ashley contributed their characters’ own spoken texts.

When I went to Iowa later that year to study with Kenneth Gaburo, I began experimenting with video in the studio created for art students by his friend Hans Breder. I discovered that the technology and real-time manipulability familiar to me from analog electronic music transferred readily to the new medium, facilitating its adaptation as an expressive platform for moving visual thinking. Everything that I’ve done in video and intermedia since them stems from that one spark in 1983.

The Vasulkas weren’t present at Kennedy’s screening, and by the time I arrived in New York in 1985 they’d long since decamped to Santa Fe (via Buffalo). I got to know them later, especially Steina, who was more directly involved in music organizations such as STEIM (a violinist by trade, she’d previously earned her living in Broadway’s pit orchestras, whereas Woody was more of a “native” cinema artist who’d studied film production in college). One of Kennedy’s assistants at the MVC event was Robert Campbell, who organized the Vasulkas’ visit to Seattle in 2014, which included exhibits and screenings at Cornish College and the UW’s Henry Art Gallery. It was there that I saw Woody for the last time. His memory was starting to flag just a bit, but he was still sharp enough to impress at the Q&A following the week’s final event, a screening of single-channel pieces at the Henry which, yes, included The Commission. I cherished our conversations about his and Steina’s key works, and about Czech opera, especially those by Janáček, whose multivalent approach to dramatic time coupled with a naturalistic approach to text delivery found analogs in Woody’s more narrative-oriented single-channel tapes, such as The Commission and Art of Memory (1987).

Indeed, as important as the Vasulkas are for their innovations in image processing and their contributions to the avant-garde language and praxis of cinematic montage, it’s the musical sophistication that often sets their work apart from their contemporaries in the field, many of them converted visual rather than time artists whose lack of sonic erudition is often brutally apparent, evinced by soundtracks thrown together from appropriated pop songs and monotonal voice-overs. By contrast, no apologies are needed for the jarring effect in The Commission when Berlioz’s first monologue is interrupted by a synthesizer tremolo on a major 6th, beginning rapidly then slowing down, the rhythm synchronized to intercutting between processed and unprocessed images. Nor need there be any misgivings about Steina’s electronic soundtrack to her epic The West (1983), which is gripping in its direct simplicity, and effective as an abstract counterweight to the grandeur of the work’s extensive nature footage. Even in the Vasulkas’ more static installation pieces, there’s a palpably musical sense of scenery—of lines that undulate, repeating their gestures in new permutations as if seeking an unattainably stable tenancy.

As another chapter closes on experimental cinema’s greatest generation—the Paiks, Vasulkas, Brakhages and Snows who represent its counterpart to the musical cohort of Cage, Sun Ra and Darmstadt—my emotions vacillate between grief and awe before settling on a sincere hope that the Vasulkas’ corpus, much of it scattered among Japanese warehouses and old-school video art distributors, can soon be made more readily available to a new generation of artists and enthusiasts.