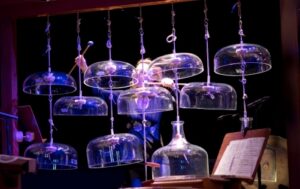

Beyond 12: Reinventing the Piano Volume 2 is a new CD release of piano music from MicroFest Records featuring Grammy-nominated pianist Aron Kallay. Beyond 12 refers to the conventional scale in Western music that has 12 equal divisions to the octave. Kallay, however, goes beyond that limitation by the use of a digital grand piano that configures the keyboard for alternate tuning systems. New pieces were solicited from eight different contemporary composers with only two ground rules: 1) Re-tune the keyboard, from extended just intonation to 88 equal-divisions of the octave and everything in between. 2) Re-map the keyboard, left can be right, high can be low; pitches need not be in order. Beyond 12 – Volume 2 vividly demonstrates the forward possibilities of alternate tuning in new music.

Sidereal Delay (2004) opens the album on track 1. This is the third piece in a suite of four preludes by Jeffrey Harrington and employs a tuning that divides the octave into 19 equal divisions. There is a lovely shower of notes at the beginning – like watching flower petals thrown into the air and fluttering down to the ground. Rapid phrases ebb and flow, then decrescendo to a brief quiet. The alternate tuning is heard, but blends so well into the melody and harmony that it becomes an expected and natural element of the music. After a brief silence, another section begins in similar form and tempo, with a rush of sunny notes running down to silence. The overall feeling is one of buoyancy and good cheer.

Subsequent sections of Sidereal Delay feature comparable structures – some have a stronger presence while others are more restrained. Kallay’s playing is rapid and accurate, without being tedious or pedantic. The expressive warmth of the composition comes through and the overall feeling is full of optimism and good will. Sidereal Delay, at slightly under 5 minutes, is a masterful application of tuning in the service of its amiable musical intentions.

I’m Worried Now, by Monroe Golden, is next and employs an alternate tuning scheme in a much different context – that of emotional tension. Golden, who hails from Alabama, uses an old chain gang folk song as the inspiration for this piece. The composer writes in the liner notes that the tuning scheme consists of “…five Extended Just tunings, (1) 13-limit with a common tone functioning as different partials, (2 and 3) microtonal bass notes with a treble drone in octaves, (4) a lower tetrachord encompassing the black keys and upper tetrachord encompassing the white keys, ranging to the 91st partial, and (5) a I-IV-V relationship with the keyboard divided into three zones, each with partials up to 23.” Despite this formidable description, the resulting music delivers a perfectly balanced sense of anxiety, sharpened by the unconventional pitches that are sprinkled throughout the harmony.

After a quietly tense opening there is a section with rapidly moving phrases in the higher registers and low notes in counterpoint below. This sounds almost ‘normal’ with the faster tempo and rhythms serving to maintain a sense of apprehension even as a lively melody emerges in the bass that borders on the jovial. A slower section follows, when suddenly a strong roar of slurred descending notes jumps out in full fury, reigniting the sense of inescapable dread. More languidly slow stretches follow, mixed with pounding passages and rapid phrases infused with disquiet, adeptly fashioned from the unconventional tuning materials. Towards the finish, the melody of a familiar hymn is heard, and the piece concludes with quietly restful chords. The wide variety of sounds and textures has Kallay all over the keyboard, but he manages to navigate each new gesture with his usual poise. I’m Worried Now brilliantly builds on its alternate tuning scheme to clearly convey emotional uncertainty within an accessible musical syntax.

The longest piece of the album is Clouds of Clarification, by Robert Carl. The composer writes that this piece represents “… a further step in developing an overtone-based harmonic practice.” Carl states that Kallay’s re-tunable digital piano “… is able to preserve the actual just intonation tuning of its twelve pitches based on overtones in relation to their respective fundamental. Thus each will be a truly ‘pure’ interval. “

Clouds of Clarification proceeds in four movements and the first, “Introduction: Ebb and Flow”, begins with strong opening chords that ring out solidly and establish a sense of anticipation. Trills, combined with a series of exclamatory notes, add a feeling of expectation. The tuning is noticeable, but not alien to the ear, and the careful handling of the just intonation intervals makes for a consistently consonant blend of pitches. Next is “Maestoso: Earth Processional” and this movement begins with a low chord that is deep and quietly mysterious. A series of repeating solitary notes add a tentative feel as more chords are heard in the middle registers along with increasing dynamics. Less confident than the opening movement, this ultimately evolves to a softer and more introspective feeling towards the finish.

The third movement, “Scherzo: Wind Dances” is just that – music full of breezy syncopated rhythms, rapid runs and repeating phrases that all combine to provide a sense of energy and freedom. Repeating chords appear with rapid arpeggios that suggest wind gusts and the music often starts and stops in fits, like a swirling breeze. A blast of hammering chords is combined with a sprinkle of rapidly descending notes to add a stormy feel. Turbulent notes spray all over the keyboard, calling on Kallay’s highest virtuosity in this whirlwind of a movement. “Coda: Consumed by Fire” completes the piece and this is also active and energetic. There are stretches with rapid, unconnected passages and gestures that suggest capricious, flame-like movement. As the piece proceeds, the tempo slows and the notes become softer and fewer, longer and with embedded silences as if the fire is burning itself out.

Clouds of Clarification is a technically challenging piece – and the listener is naturally drawn to the velocity and agitation of the notes. The polish of the just intonation tuning, however, provides a sonority that artfully mirrors the surfaces of the natural phenomena portrayed in each of these four colorful movements.

Veronika Krausas has contributed two miniatures to the album, the first being Une Petite Bagatelle written in 2013. Built around 2/7 comma meantone tuning, this piece fully embraces the playfulness of its title. Une Petite Bagatelle opens with a brilliant flurry of notes that reach upward in a series of bright tones. This phrasing repeats and the piece then continues with a strong melody line and deep chords in the bass. The alternate tuning here adds an impish shimmer to the texture that is very appealing.

Terços, the second piece, was commissioned for this CD and opens with a series of meandering phrases that suggest uncertainty. A distinctive melody arises from the tuning with a hard, sparkling surface that is pleasantly engaging to the ear. Another wandering set of phrases and some simple chords that hint at mystery conclude the piece as the final chords ring out nicely. Tercos and Une Petite Bagatelle, although concise, adroitly exploit the aesthetic implications of their alternate tuning.

Involuntary Bohlen Piercing, by Nick Norton, originated as an academic assignment requiring that a new piece be conceived and completed in 48 hours. In order that it should be completely original – and also meet the specifications of Beyond 12 – Norton chose the Bohlen-Pierce alternate tuning scheme. The composer writes: “Bohlen-Pierce temperament uses the 12th instead of the octave as the interval of transposition and inversion, and then divides that 12th into thirteen step equal temperament. The result of it is that everything sounds crazy.”

Involuntary Bohlen Piercing begins with deep, dark chords followed by series of halting, off-beat notes and a smattering of higher register runs above. The unconventional tuning is conspicuous throughout, bringing a recognizably alien feel to the repeating phrases and exclamatory chords as the piece proceeds. The texture soon thickens with booming chords below and runs of higher notes above that serve to heighten the anxiety. The tempo then begins to slow, and the density of notes thins out, but the tension remains. Even as the final phrases die quietly away, a strong sense of the unusual persists. Involuntary Bohlen Piercing is a particularly well-crafted example of how thoroughly the tuning scheme can pervade and influence every aspect of a piece.

The Blur of Time and Memory, by Alexander Elliott Miller, was written in 2014 specifically for the MicroFest Beyond 12 series. The composer writes that this piece “… utilizes a tuning system in which half steps are divided into five equal tempered steps, but selected pitches are removed from the keyboard in segments altogether, allowing the 88 keys to cover a wider range.” The editing out of some notes within an alternate tuning scheme is a common practice by composers working with many divisions of the octave and in this piece it becomes possible to have stretches of conventional harmony as well as completely new effects.

The Blur of Time and Memory begins with an arpeggio and a series of pensive notes in the middle and lower registers. This is followed by several chords that fully expose the alternate tuning. There is a sense of controlled unease in the quiet stretches and a more assertive tension when the density and dynamics increase. The closeness of the pitches in the expanded half-steps add a distinctive blurring effect to the melody. Five divisions to the half-step is surely an exacting challenge for any pianist, and Kallay here further advances his claim to alternate tuning excellence; his sure touch propels the piece forward with a gentle ebb and flow between the softer and stronger passages, as if in a dream. The Blur of Time and Memory is solidly crafted and makes full use of the many pitches in its tuning palette to add new emotional colors to the harmony and phrasing.

Track 11 contains Paths of the Wind, by Bill Alves, composed in 2010 and is dedicated to Aron Kallay. Inspired by the Vayu Purana, a Hindu text, the composer writes that the tuning is “…based on interlocking pathways of numbers, namely two, three, and seven.” Opening with a low, repeated rumbling in lower registers with a single repeated note slightly higher in pitch, there is an immediate sense of expectation. The intrigue builds as more notes and chords are added in the middle registers and the roiling texture produces a beautifully awesome sense of natural power. The alternate tuning is an integral part of the sound, but not the most distinctive element – this remarkable portrayal of the wind is almost completely captured through the thickening texture. As the dynamics and complexity build relentlessly, it seems that Aron Kallay must have at least 15 fingers to produce such a prodigious outpouring of sound.

At 5:00, however, there is a sudden reduction to a few repeating high notes and a running figure slightly below – just a trickle of what had previously been a flood. A sense of peaceful serenity emerges like a gentle breeze after a storm. A few dark chords appear, suggesting a distant menace, but the music gracefully fades to a quiet finish. The thick, repeating phrases, the fluid feel and Kallay’s impressive playing make Paths of the Wind a striking musical description of a powerful natural force.

The final track on the album is The Weasel of Melancholy, by Eric Moe, written during 2013 and commissioned by Aron Kallay. Inspired by traditional Thai music, this piece is constructed from a seven-note scale with half-steps added to produce a 14 pitch palette in equal temperament. Weasel opens quietly, with a serene and mostly conventional feeling. The melody above and counterpoint below combine with the alternate tuning notes to add just the right amount of introspective coloring. This settled and somber sensibility is heightened, but never dominated, by the unconventional tuning and the piece strikes a deft balance between familiar and new pitches within the 14 step scale. Towards the finish the tempo slows as the number of notes thin out and the piece glides to a subdued conclusion. The Weasel of Melancholy artfully leverages its straightforward tuning construction to create a carefully blended depiction of the mournful shades of melancholy.

That all of the pieces on this album employ alternate tuning is a great advantage to the listener. The ear becomes more accustomed to the presence of new pitches and less distracted by preexisting expectations. The exacting performances by Aron Kallay only add to the accessibility of this music. The composers who have contributed to this project are, in a sense, genetic engineers. Each composition on Beyond 12: Reinventing the Piano – Volume 2 widens the listener’s understanding of how tuning is foundational to the DNA of all music.

Beyond 12: Reinventing the Piano, Vol 2 is available from direct from MicroFest Records and Amazon Music.