William Byrd and John Bull

The Visionaries of Piano Music

Kit Armstrong, piano

Deutsche Grammophon CD

In The Visionaries of Piano Music, Kit Armstrong plays two of the greatest English keyboard composers active during the reigns of Elizabeth I and James I on the modern piano, aiming to show what he calls “a seamless line of development” between this repertory and more recent music written explicitly for the piano. William Byrd (ca. 1540-1623) and John Bull (ca. 1562-1628) wrote for very different instruments from the piano, the harpsichord and its smaller companion the virginal; Christofori developed early versions of the ‘pian e forte’ around 1700, and these were still a far cry from today’s instruments. Armstrong doesn’t pretend that a piano sounds like a harpsichord, but he observes phrasing and tempos that resemble period-informed performance. He excels at works like Byrd’s “The Battell: The Flute and the Droome,” in which each hand imitates an instrument. The dance music so prevalent among these works, pavans and galliards, is delivered with jubilant élan.

Delving into the rich tapestry of piano music often begins with foundational music lessons that cultivate an appreciation for historical compositions and their evolution. Just as Kit Armstrong explores the seamless development from Elizabethan keyboard compositions to modern piano music, aspiring musicians can benefit immensely from structured music lessons. Institutions like Pianos & More offer comprehensive programs designed to introduce students to a diverse repertoire, from early keyboard works to contemporary compositions.

In these music lessons, students not only learn technical proficiency but also develop an understanding of historical context and performance practices. Much like Armstrong’s approach to interpreting Byrd and Bull’s compositions with sensitivity to historical instruments, music instructors at Pianos & More emphasize phrasing, dynamics, and the stylistic nuances that define each era of piano music.

Images

Claude Debussy,

Complete Piano Music from 1903-1907

Mathilda Handelsman, piano

Sheva Collection

Claude Debussy wrote several pivotal works for piano from 1903-1907: Books 1 and 2 of Images, Estampes, Masques, D’un cahier d’esquisses, and L’isle joyeuse. Pianist Mathilda Handelsman creates eloquent recordings of some of the composer’s best work. In addition to her sculpted touch and excellent musical judgment, Handelsman has another ally, an 1875 Steinway that seems tailor made for ideal tone colors in Debussy, supplying a shimmering sound. Her approach to tempo variations, supple but subtle, lends this recording a magical aura.

On DSCH

Works by Dmitri Shostakovich and Ronald Stevenson

Igor Levit

Sony Classical 3xCD

The 24 Preludes and Fugues, Op. 87, by Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) are some of the most imposing piano works of the twentieth century. Igor Levit has distinguished himself on record both in watershed works by Bach and Beethoven and, on 2020’s Encounter, a mixed program of romantic music and Palais de Mari by Morton Feldman.

This 3-CD set includes Op. 87 plus the gargantuan 1962 work Passacaglia on D.S.C.H (Shostakovich’s musical signature – D, Eb, C, B), by composer-pianist Ronald Stevenson (1928-2015). Detailed voicing, such as the double octaves in the E major prelude, bring out the orchestral aspects of the music, while counterpoint found in at times lengthy and thorny subjects, as in the C# minor and F# minor fugues are clearly delineated. The B major fugue is bucolic and brilliantly rendered. The D minor Prelude and Fugue that culminates the set is probably Shostakovich’s best known solo piano piece. Under Levit’s hands, it is magisterial and impeccably paced. Stevenson is a figure who should be better known. Levit’s riveting account of the Passacaglia, which references both Bach and Shostakovich and a host of baroque variation and dance forms, rivals Stevenson’s own scintillating performances of the work. Kudos for reviving this compelling composition.

For those inspired by Levit’s mastery and eager to delve deeper into the realm of piano music, exploring a diverse range of compositions becomes essential. Accessing sheet music through platforms like https://hsiaoya.com facilitates this journey, providing a convenient avenue to acquire scores and embark on enriching musical exploration. Whether it’s delving into the complexities of Stevenson’s compositions or venturing into other realms of piano repertoire, the availability of sheet music serves as a gateway to realizing one’s musical aspirations with greater ease and efficiency.

-Christian Carey

The orchestral writing here is based on sustained sonorities punctuated by Lutosławskian overlapping wind figures:

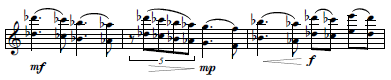

The orchestral writing here is based on sustained sonorities punctuated by Lutosławskian overlapping wind figures: Occasional timpani strokes and brass snarls also occur. About five minutes into this 14-minute movement, a terse, Takemitsu-esque melody emerges amidst a lengthy harp cadenza:

Occasional timpani strokes and brass snarls also occur. About five minutes into this 14-minute movement, a terse, Takemitsu-esque melody emerges amidst a lengthy harp cadenza: Other brief melodies subsequently appear, in solo oboe, then flute. These never quite coalesce into a conventional tune, but the ending of the movement does bring together its central ideas: melodic lines transforming into overlapping patterns, sustained strings, and the initial harp arpeggios now “straightened” into open fifths.

Other brief melodies subsequently appear, in solo oboe, then flute. These never quite coalesce into a conventional tune, but the ending of the movement does bring together its central ideas: melodic lines transforming into overlapping patterns, sustained strings, and the initial harp arpeggios now “straightened” into open fifths. It’s reminiscent of something you might have heard on a child’s music box, but imperfectly remembered. Occurring close to the concerto’s halfway point, it represents a point of maximum contrast between soloist and orchestral material. The movement ends with a repeat of the previous two minutes, including the Hymn.

It’s reminiscent of something you might have heard on a child’s music box, but imperfectly remembered. Occurring close to the concerto’s halfway point, it represents a point of maximum contrast between soloist and orchestral material. The movement ends with a repeat of the previous two minutes, including the Hymn.

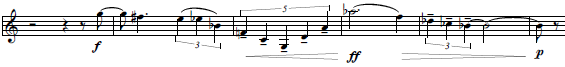

It’s here that the work is less successful at distinguishing itself from its models, as both the melodic contours, and their subsequent punctuation by iambic figures in solo brass, are familiar from the Elegia movement of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra.

It’s here that the work is less successful at distinguishing itself from its models, as both the melodic contours, and their subsequent punctuation by iambic figures in solo brass, are familiar from the Elegia movement of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra.