Jerry sent me a box load of CDs for review under the agreement that I will choose lesser-known composers. So a new column called “Lost and Found” is born, and will (hopefully) be an every-other week installment.

American Women: Modern Voices in Piano Music (self-published)

American Women: Modern Voices in Piano Music (self-published)

Nancy Boston, piano

In American Women: Modern Voices in Piano Music, Nancy Boston explores piano literature from American women composers, or less specifically American composers. The recording title could do without the introductory gender reference, despite Ms. Boston’s good intentions. The music featured here represents American composers, in the same way an all male recording (often the case) represents American composers. The fact that we call attention to the femininity of this collection doesn’t change our impressions, good or bad, of the notes.

The music on Modern Voices in Piano Music represents a style of writing on par with some of the great piano composers (Schumann, Chopin, Debussy, etc). From the character pieces of Nancy Bloomer Deussen (Two Pieces for Piano), Judith Lang Zaimont (Suite Impressions), Beth Anderson (September Swale), and Beata Moon (Piano Fantasy), to the larger sonatas of Nancy Galbraith and Emma Lou Diemer.

In each case, these fine composers have shown their ability to write for an instrument that can so often be treated poorly. On occasion the music was too “easy” for my taste, but I’m just another listener. Nancy Boston’s performances are convincing and inspired, partly due to her affinity for the “cause” of women composers. Let’s hope that music by women continues to be considered equal to their brethren through performers like Nancy Boston.

The Louisville Project (Arizona University Recordings 3127)

The Louisville Project (Arizona University Recordings 3127)

Richard Nunemaker, clarinet

Featuring: Andrea Levine, Dallas Tidwell, Timothy Zavadil, clarinets; The Louisville Quartet (Peter McHugh and Marcus Ratzenboeck, violins; Christian Frederickson, viola; Paul York, cello); Krista Wallace-Boaz, piano

Richard Nunemaker’s CD published by Arizona University Recordings presents works composed since 2000, and recorded (mostly) in Louisville during 2003. This recording is dedicated to the memory of M. William Karlins (1932-2005), one of the composers featured on the disc, and one who was present at the recording of one of his works.

Rothko Landscapes (2000) by Jody Rockmaker is meant to be a musical realization of Rothko paintings and utilizes quite a bit of extended techniques. Rockmaker’s use of visual allusions doesn’t impede or help the listener, as the music stands on its own.

Marc Satterwhite’s two offerings Clarinet Quintet(2002) and Las viudas de Calama (The widows of Calama) (2000) use the clarinet in a more melodic way than other works on this disc. The Clarinet Quintet, scored for string quartet and clarinet (B-flat and bass), is a compelling work with long phrases and a scoring that is always careful and delicate. Las viudas de Calama is based on a poem of Marjorie Agosin, a Chilean writer, describing the atrocities of the Pinochet regime in a city called Calama, situated in the Atacama Desert. Agosin’s chilling prose, which seems particularly relevant in light of the recent death of Pinochet, is translated into a work for bass clarinet and piano.

Karlins’ work is characterized by long phrases and soft dynamics, requiring skillful breathing and careful articulation. Just a Line from Chameleon makes proud of the fact that it is composed “in registers of the instrument that are difficult to control at a soft dynamic level.” Improvisation on “Lines Where Beauty Lingers” is based on a jazz tune by Ron Thomas.

Meira M. Warshauser pairs two bass clarinets against each other, describing tensions and commonalities (past and present) between the descendants of Ishmael (Palestinians) and Isaac (Israelis). The title Shevet Achim (Brothers Dwell) is taken from Psalm 133, v. 1 “How good and how pleasant it is when brothers dwell together as one.”

Michael Hersch Symphones Nos. 1 and 2 (Naxos 8.559281)

Michael Hersch Symphones Nos. 1 and 2 (Naxos 8.559281)

Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra

Marin Alsop

It is always an accomplishment to have an orchestral work performed. Greater still is to have that work performed and recorded by a leading orchestra and a conductor who is an avowed promoter of new music. Marin Alsop and the Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra have done so by recording four orchestral works by Michael Hersch (b. 1971) on the Naxos label, a company that never seizes to amaze in the risks they take.

Hersch’s Symphony No. 2 (2001) is a prime example of today’s typical orchestral composition: Sweeping crescendos, large chords filled with brass and percussion and punctuating gestures. Melodies are largely absent, and when they do appear, are short-lived, though not unskillful. The third movement offers a peek into a melody, one we could use more of. His first symphony from 1998 is an early, Second-Viennese-School-influenced work, with perhaps a few more tunes and weaker orchestrations.

Both Fracta (2002) and Arraché (2004) display a more “modern” style and, again, the kind of writing that appeals to the large orchestral sound. Arraché includes some fugal writing, and by implication melodies, though the modern clichés are never far off. Fracta is a reworking of an earlier chamber work, accompanied by a poem by Friedrich Hölderin.

Disasters of the Sun (Canadian Music Centre 11806)

Disasters of the Sun (Canadian Music Centre 11806)

Barbara Pentland, composer

Judith Frost, mezzo-soprano

Turning Point Ensemble

Owen Underhill

Barbara Pentland deserves a bit of introduction. Born in Winnipeg in 1912, Pentland began composing around age nine, but was plagued with bad health and strict parents, both which impeded her compositional growth and studies. While living in Paris, she was “allowed” to study composition, and did so under Vincent d’Indy. After returning to the North American continent, Pentland received a fellowship to study at Juilliard and studied with Copland in Berkshire. It was a trip to Darmstadt and exposure to Webern, through Dika Newlin, that turned her compositional voice from a style influenced by d’Indy to the post-serial style en vogue during the late 40’s and 50’s.

The works on this Canadian Music Centre release, represent works from the late 70’s to mid 80’s, and one work from her “early” period. The largest work (both in time and performing forces) is Disasters of the Sun (1977) for mezzo-soprano and chamber ensemble, based on a text of Dorothy Livesay (1909-1996), whom Pentland met in the 30’s. This is a dramatic work requiring thirty minutes of athleticism from the singer, and complex rhythmic counterpoint for the chamber orchestra. Commenta and Quintet for Piano and Strings, date from 1980-1981 and 1983, respectively. All three of the aforementioned compositions make generous use of extended and improvisatory techniques, but never stray from a lyrical writing, even if it’s rigid. The Octet for Winds is a neo-Classical work from 1948 composed while Pentland was at the MacDowell Colony (it was here where she met Dika Newlin), but begins to incorporate serial techniques (with a nod to Stravinsky). The Canadian Music Centre website (http://www.musiccentre.ca/) has a good biography, along with audio and score samples.

Anyone who’s dabbled even casually with the music world knows it’s full of heartbreak, exhilaration, passion, and drama. A profession overstuffed with possibilities for storytellers in all media, it’s a wonder to me why more film directors, novelists, and playwrights don’t take the plunge.

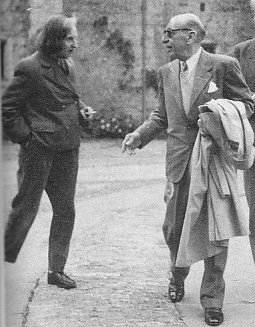

Anyone who’s dabbled even casually with the music world knows it’s full of heartbreak, exhilaration, passion, and drama. A profession overstuffed with possibilities for storytellers in all media, it’s a wonder to me why more film directors, novelists, and playwrights don’t take the plunge. Five minutes before Elisabeth Lutyens appeared live on BBC Radio 4’s ‘Start the Week’ in 1979 she threatened to denounce Russell Harty as a ‘homosexual interviewer’ if he mentioned the phrase ‘lady composer’; thankfully Harty avoided using the words when the programme was on air. Lutyens was a larger than life personality who pioneered serial techniques in her unfairly neglected music. She was also well connected as my photo shows. For the full story, and a recommendation of a new CD of her music, click on

Five minutes before Elisabeth Lutyens appeared live on BBC Radio 4’s ‘Start the Week’ in 1979 she threatened to denounce Russell Harty as a ‘homosexual interviewer’ if he mentioned the phrase ‘lady composer’; thankfully Harty avoided using the words when the programme was on air. Lutyens was a larger than life personality who pioneered serial techniques in her unfairly neglected music. She was also well connected as my photo shows. For the full story, and a recommendation of a new CD of her music, click on