This Fall marks the twentieth season of provocative programming in New York City brought to you by Interpretations. Founded and curated by baritone Thomas Buckner in 1989, Interpretations focuses on the relationship between contemporary composers from both jazz and classical backgrounds and their interpreters, whether the composers themselves or performers who specialize in new music. To celebrate, Jerry Bowles has invited the artists involved in this season’s concerts to blog about their Interpretations experiences. Our first concert this season on 2 October, features the Myra Melford Quartet and Henry Threadgill’s Zooid + Talujon Percussion Ensemble. Michael Lipsey of Talujon has volunteered to write about how his group worked with the Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust to commission a new work from Henry Threadgill:

This Fall marks the twentieth season of provocative programming in New York City brought to you by Interpretations. Founded and curated by baritone Thomas Buckner in 1989, Interpretations focuses on the relationship between contemporary composers from both jazz and classical backgrounds and their interpreters, whether the composers themselves or performers who specialize in new music. To celebrate, Jerry Bowles has invited the artists involved in this season’s concerts to blog about their Interpretations experiences. Our first concert this season on 2 October, features the Myra Melford Quartet and Henry Threadgill’s Zooid + Talujon Percussion Ensemble. Michael Lipsey of Talujon has volunteered to write about how his group worked with the Mary Flagler Cary Charitable Trust to commission a new work from Henry Threadgill:

Contemporary music is exciting. People are trying new things, creating new works, involving new audiences members. The division between genres is the most open it has ever been. With that in mind, Talujon Percussion, Henry Threadgill and Zooid have teamed up to play on the Interpretations Series in honor of the series’ 20th season.

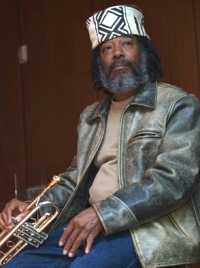

Henry Threadgill is one of the most unique voices in contemporary improvisatory music. His resume is breath-taking, his skills are immense and his interests are wide and varied. About two years ago, Henry called me up a day before a Talujon concert. He told me he was interested in the group and wanted to come to our performance. We were happy to meet him and honored that he would come to one of our performances.

Henry Threadgill is one of the most unique voices in contemporary improvisatory music. His resume is breath-taking, his skills are immense and his interests are wide and varied. About two years ago, Henry called me up a day before a Talujon concert. He told me he was interested in the group and wanted to come to our performance. We were happy to meet him and honored that he would come to one of our performances.

A few days after the performance, Henry again called and asked if we would be willing to work on a new work. The answer was, of course, “Yes”. Henry decided to write a piece for Talujon and his ensemble, Zooid. We ended up applying to the Mary Flagler Carey Trust for the commission. We have used that commissioning vehicle in the past. Through this organization we were also able to commission a work for 4 drum sets by Julia Wolfe.

After meeting with Henry, he decided to compose a piece for each individual in Talujon.

We all gave Henry our wishlist of instruments. Henry then used our strengths in his composition. The piece that came out of this process uses four of our members, each with our own set-up. The piece is called “Fate Cues”.

We start rehearsals tomorrow and we are all excited. If you listen to Henry’s works you find that he is a fluid composer. He is continually asking more from the players. The charts are difficult, but that is not the emphasis of his works. He wants the musicians to move through the piece together as a strict unit. Each voice in individually created but maintaining its own presence. The rehearsal process is key.

Talujon is a group that has 18 seasons of unity. We know each other and feel very comfortable with each other. Much like any ensemble, we can feel our musical relationships and know how to support one another. We like to experiment and have practiced improvisation many, many times. Jazz improvisation is different than what we are used to. First, we just need to get past feeling uncomfortable about improvising in front of these great jazz masters in Zooid. I think that part will be ok. All the members have been in these situations before and as a group; Talujon thrives on making the uncomfortable, comfortable.

We like challenges and Henry is open and excited about the challenge.

It should be fun 🙂

*****

Myra Melford Quartet: Happy Whistlings; Henry Threadgill’s Zooid + Talujon: Fate Cues

Thursday October 2, 2008, 8pm at Roulette.

more information / Interpretations

Baritone Eric Owens is busy this fall – his Met debut as General Leslie Groves in John Adams’ Dr. Atomic is just a start to his performances this season in New York, Atlanta, London and Los Angeles.

Baritone Eric Owens is busy this fall – his Met debut as General Leslie Groves in John Adams’ Dr. Atomic is just a start to his performances this season in New York, Atlanta, London and Los Angeles.

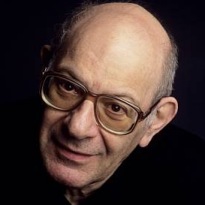

Wadada Leo Smith has a philosophy from which he composes. From our seats we could see both the piano score and the conducting score Smith used. This view made it clear how much improvisation went into the performance, and how much advance thought and consideration had preceded the improvising. A page of Smith’s conducting score, for example, had four rectangles and looked rather like a top-level conceptual diagram of a complex computer system. This page of the score covered three or four minutes of ensemble work and solos; during the period Smith might stop conducting and just listen before using his hands to regain the attention of the musicians before setting the beat and cuing the entrances for the next step in the evolution. Smith has developed a notation system called “Ankhrasmation”; he summarizes it

Wadada Leo Smith has a philosophy from which he composes. From our seats we could see both the piano score and the conducting score Smith used. This view made it clear how much improvisation went into the performance, and how much advance thought and consideration had preceded the improvising. A page of Smith’s conducting score, for example, had four rectangles and looked rather like a top-level conceptual diagram of a complex computer system. This page of the score covered three or four minutes of ensemble work and solos; during the period Smith might stop conducting and just listen before using his hands to regain the attention of the musicians before setting the beat and cuing the entrances for the next step in the evolution. Smith has developed a notation system called “Ankhrasmation”; he summarizes it  From that high point, the festival moved higher, with a set of works by

From that high point, the festival moved higher, with a set of works by  The second half of the program stepped back to the merely pleasant with

The second half of the program stepped back to the merely pleasant with

This is the score for “Piece in the Shape of a Square” spread out across the stage at the Players Theatre. Tonight in Manhattan at 8:00 PM we’re celebrating the 50th anniversary of the birth of Minimalism with a concert of Steve Reich’s “Piano Phase,” two “Piano Pieces” by the obscure but great Terry Jennings, Terry Riley’s “In C,” and this piece by Philip Glass.

This is the score for “Piece in the Shape of a Square” spread out across the stage at the Players Theatre. Tonight in Manhattan at 8:00 PM we’re celebrating the 50th anniversary of the birth of Minimalism with a concert of Steve Reich’s “Piano Phase,” two “Piano Pieces” by the obscure but great Terry Jennings, Terry Riley’s “In C,” and this piece by Philip Glass.