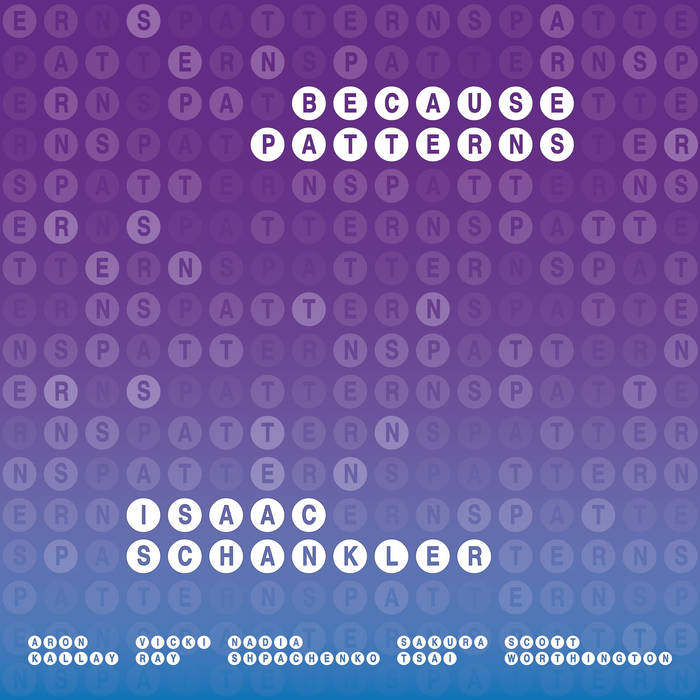

Aerocade Music’s Because/Patterns is an album of experimental music by composer Isaac Schankler. Three new works are featured and performed by top Los Angeles-area musicians. Each piece is the product of the relationship that develops between the acoustic instruments and accompanying electronic constructions. Schankler is perhaps best known as the artistic director of People Inside Electronics, an organization dedicated to ambitious and innovative uses of electronics in new concert music. This album marks the high level of his efforts in this area.

The first piece is Because Patterns/Deep State, with Aron Kallay on piano, Vicki Ray on prepared piano and Scott Worthington playing bass. This begins with an electronic track full of sharp rattling rhythmic sounds that alternate on both channels. Deep, booming bass sounds from Worthington occur at regular intervals, followed by a whirring sound that increases in loudness and finally dominates. Some quietly repeating piano notes slowly push their way into the texture, gaining quickly in volume and creating a nice rhythmic groove in the process. The whirring returns, accompanied by drumming and a variety of industrial sounds – humming, buzzing, clicking and rumbling – these are imposing, although not quite menacing. A siren is heard in the foreground, sustained and urgent, building a sense of anxiety.

Synthesized string sounds appear like the sunrise on a cool morning invoking a more hopeful and optimistic feeling. As the whirring and drumming recede, a light rain of appealing piano notes is heard and soon dominates to bring a welcome sense of cheer. The ominous electronic sounds, however, return to continue the pattern of alternating layers that rise and recede as the piece moves forward. The piano playing by Kallay and Ray is warm and lyrical – immediately recognizable as inspired by human creativity. The deep electronics are never menacing, but always stand apart from the music.

As the dark mechanical sounds recur, they evoke the regimented constraints of a modern existence. When the lighter piano notes appear with their optimistic tones and agreeable rhythms, we are reminded of those times when our humanity is allowed to prevail. These two states struggle for control, but neither seems able to completely displace the other. The persistence of optimism is the message here; life is never so grim that all possibility of hope is extinguished. Because Patterns/Deep State is an artful exploration of the contending forces present in our culture, and offers a powerful assurance of human resilience.

The second work, Mobile I, features violinist Sakura Tsai along with electronic accompaniment enhanced by spectral analysis. This opens with sustained notes in the violin followed by a pause and then some light skittering with pizzicato that builds tension. The sustained tones return, but are now accompanied by a pure electronic tone that shines like a cool beacon through the increasingly complex flow of phrases issuing from the violin. The electronic tones vary in pitch but never overwhelm, acting like a calm backdrop to the now frenzied passages expertly played by Sakura Tsai. The tension ratchets higher as rough, scratchy sounds evoke a convincing sense of suffering and agony. The electronics now become more animated and percussive, adding to the level of anxiety. The violin finally breaks out in a series of fast, nicely articulated phrases, as if sprinting towards freedom before fading at the finish. Mobile I artfully contrasts the vividly expressive sounds of the violin with more reserved tones from the electronics, a combination that, surprisingly. works to magnify the emotional response of the listener.

The final track is Future Feelings and features pianist Nadia Shpachenko. This opens with a lightly metallic wash in the electronics and swirls of strong piano notes. As the piece moves forward, the piano dominates, unreeling clouds of lovely phrases played with that characteristically sensitive Shpachenko touch. Although for the most part quietly atmospheric, some drama is occasionally added when the piano dips into the lower registers in a series of rapid, descending scales. Soft beeping tones – clearly electronic – enter from underneath, yet these seem perfectly at home embedded within the lush melodies and warm textures of the piano line. The extravagantly beautiful playing of Ms. Shpachenko almost steals the show, but the subdued electronic presence is memorable precisely for how much it contributes to the warm sensibility of this piece. Future Feelings is exquisitely expressive music, with just the right balance of masterful playing and superbly complimentary electronics.

Because/Patterns is remarkable listening and a new benchmark of just how highly evolved the combination of acoustic instruments and electronics has become in the service of musical expression.

Because/Patterns is available now via digital download from Bandcamp, Amazon, Spotify, and other retailers. A 12” vinyl record with a unique color or pattern combination and can also be ordered via Bandcamp.