One of the focuses of this year’s Proms, concentrated during the month of August, was the centennial of György Ligeti. The first of these, presented on August 11 by The London Philharmonic Orchestra, along with the London Philharmonic Choir, the Royal Northern College of Music Chamber Choir, and the Edvard Grieg Kor, conducted by Edward Gardner, started in what might be the most obvious place, especially for drawing a large audience, focusing on the music used in Stanley Kurbrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey. The movie certainly introduced Liget’s music to a larger audience than it had ever received before that time, and made him a sort of star, both of in new music circles and in the world at large. This concert included Ligeti’s Requiem and Lux Aeterna, and ended, inevitably, with Also sprach Zarathrustra by Richard Strauss. Robert Stein’s program note asserted that Ligeti’s Requiem, composed from 1963 to 1965, was an unexpected next piece to follow his Poèm symphonique, for 100 metronomes, of 1962, but in fact the micropolyphony of the choral and orchestra work is a pretty exact recreation of the texture produced by many metronomes clicking away simultaneously. In the Requiem, Ligeti aligns that micropolyphonic texture with a quite remarkable and highly personal sense of register and orchestral color, producing a new and striking musical character at just about every moment. The Lux Aeterna, for 16-part unaccompanied chorus, written in 1966, which was performed by the Edvard Grieg Kor, is more concentrated and refined, and even more striking, being a distillation and, if you like, condensation of the Requiem for sixteen unaccompanied voices. All of the performances were beyond reproach.

The Prom on August 15, presented by the Royal Philharmonic, conducted by Vasily Petrenko, started with Lotano by Ligeti. Written in 1967, Lotano is in the vein of the Requiem and Lux Aeterna, but concentrates on luminous orchestration. Lontano was followed by the Beethoven Fourth Piano Concerto, with Alexandre Kantorow, as soloist, in what seemed to me to be the best performance of anything I’d ever heard, Kantorow, as an encore, delivered a radiant performance of somebody’s arrangement of the Finale from The Firebird. The concert ended with the Shostakovich Tenth Symphony, written in 1953. Shostakovich had suffered serious humiliation and oppression during the later 1940s and early 1950, a certain amount of it aimed directly at him by Stalin. During that time he wrote a number of pieces which he simply didn’t release, realizing that they would cause him even more trouble. Stalin’s death in March of 1953 was a source of relief for the composer, and the Symphony seems to be a powerful expression both of that relief and its attendant relative freedom, as well as a reflection on aspects of the situation. The second movement, which is a relentless and caustic scherzo is said to be a portrait of Stalin. The performance of the piece was vivid and powerful. The whole concert was unforgettable.

The Prom on the evening of August 13 was presented by The Budapest Festival Orchestra, conducted by Iván Fischer, on the heels of their Audience Choice Proms that afternoon, in which the audience chose the program by vote as it went along, working from a menu provided to them. The evening began with Mysteries of the Macabre by Ligeti, an excerpt from his opera Le Grand Macabre, consisting of an aria for the Chief of the Secret Political Police, arranged by Elgar Howarth. The soloist for this was Anna-Lena Elbert, who, as was appropriate to the music it dramatic situation in the opera, was all over the stage, in a manner just as frenetic as the music she was singing. She was singing in German, but the text came think and fast and relentlessly, so one wasn’t able to actually get any words at all, which didn’t in any way detract from the absurd and funny effect of the piece. This was followed by Béla Bartok’s Third Piano Concerto, with Sir András Schiff as soloist. It received a lovely and heartfelt performance, as was appropriate to the valedictory nature of the piece. The concert concluded with the Beethoven Third Symphony. The playing all the way through the concert was as good as one could have ever expected.

The impression that Ligeti was presented only as the composer of his modernist, micropolyphonic, Space Odyssey music was rectified by the Prom on August 20, presented by Les Sièles and its conductor François-Xavier Roth. This concert included the Concert Românesc, representing the highly polished Bartokian music, infused with folk-like material, that Ligeti wrote before he fled Hungary for the west in 1956 and the Violin Concerto of 1989-93, with soloist Isabelle Faust, which gave full evidence of the highly multifaceted, multisourced and, at least for this listener, more fully satisfying music that he was writing toward the end of his life. The character of the two works and the progress and shape of each, are not dissimilar, even though the later piece is freer in its incorporation of different tunings and more ‘exotic’ instruments, such as ocarina and swanee whistles. It conveys the sense of Ligeti as a continually inquiring and endlessly curious musical personality. Les Siècles specializes in playing instruments and tunings appropriate to the particular repertory they are performing, so the Ligeti pieces on the first half of the concert were performed on modern instruments tuned to A=442Hz; the Mozart works on the second half of the concert, the 23rd Piano Concerto, with soloist Aleander Melnikov, and the 41st Symphony, were performed on Classical-period instruments tuned to A=430Hz.

All of these concerts can be heard on the BBC Sounds website.

Every Living Creature

Choral music by Kenneth Leighton

Rebecca Lea, Nina Bennet, soprano; Ciara Hendrick, mezzo-soprano;

Nick Pritchard, tenor

Finchley Children’s Music Group, Grace Rossiter, music director

Londinium, Andrew Griffiths, director

SOMM Records

Kenneth Leighton (1929-88) was a distinguished composer and academic. He taught at various places, including Oxford where he had studied as an undergraduate, spending the bulk of his academic career at the University of Edinburgh. He wrote in many genres, but it is his music for choirs that is most prized. His choral music is rigorous in construction with vibrant rhythms and skilful formal designs; tonal, but never overly sentimental. Every Living Creature, performed by Londinium, the Finchley Children’s Music Group, and a quartet of vocal soloists, conducted by Andrew Griffiths, is one of the finest recordings I have yet heard on the SOMM imprint, with a lively reverberant acoustic and wide dynamic range. It also contains a number of first recordings. Prior to the recording, some of the scores were not even published, languishing in library collections.

The centerpiece of the recording, Laudes Animantium, Op. 61 (1971), is a celebration of animals, with a variety of poets’ observations of creatures real and fanciful. Leighton himself was an animal lover, with a cat, rabbit, and dog who he often watched playing with his children in the yard. His faithful labrador retriever would sit at his feet while he composed, only stirring when Leighton played a chord or two that displeased him.

The piece’s Prelude is from Song for Myself by Walt Whitman, the author describing animals as peaceful, ideal companions. Tenor Nick Pritchard, who gives several standout performances on the recording, sings the Whitman poem with a sweet-toned lyrical voice and excellent diction. Rebecca Lea sings with purity and beauty, animating the subjects of many of the movements. Soloists from the choir, Arielle Lowinger and Madeleine Napier, deserve plaudits as well for their singing, performing with fetching delicacy in “The Lamb.”

The mood of the cycle shifts between movements, with a lively scherzo, “Calico Pie,” a dramatically imposing “The Tyger,” and a truly terrifying depiction of “The Kraken.” Throughout, the choir is expressive and finely honed in its accuracy. Griffiths’s direction keeps the counterpoint clean and the tempos fluid. The end of the cycle, “Every Living Creature,” is impressive, with soloists and choristers joining in a piece that could well be an excerpted anthem to conclude a celebration of animals in any Episcopal church with the performing forces to attempt it. Griffiths and company have set a high bar.

“An Evening Hymn” and “Lord, When the Sense of Thy Sweet Grace” also feature Lea as soloist, her tone and dynamic control impeccable. Hushed singing begins the Evensong anthem, gradually growing, with free counterpoint juxtaposed against lush verticals.

“London Town” is a powerful piece, with the choir opening up to clarion fortissimos in its climaxes. “Three Carols” are quite lovely and would enhance many a Christmas Eve service. “Nativitie” features homophonic polychords alternating with tight canons. As the piece progresses, the lines get longer and are buoyed by chords, ending with a well executed pianissimo cadence. The final piece on the recording is “The Hymn to the Trinity,” which explores Lydian melodies and staggered cadences, a repeating homophonic passage tying things together. The latter half features brisk overlapping melodies. The Lydian returns, followed by a bright amen cadence, It is a moving close to a disc of great discoveries. Someone please publish this music and distribute it widely.

-Christian Carey

The late night Prom on August 9, was billed as Mindful Mix Prom. It was presented by Ola Gjello, along with Ruby Aspinall, the Carducci String Quartet, and VOCES8. It was a little difficult initially for one to know exactly what one was in store for. The advanced material invited one to “relax into a late night musical meditation” which would explore “the universal, timeless themes of night, stillness and prayer through the lens of composers old and new,” with a playlist that “drifts from Renaissance to Radiohead.” In a Proms program for an earlier concert, Tom Service’s “The Proms Listening Service” had promised “carefully curated music designed to put us in a hypnotic nocturnal reverie.” Among the composers listed in this Prom’s program, aside from Gjello, were Caroline Shaw, Philip Glass, Roxanna Panufnik (with a work commissioned by the BBC for this concert), Ken Burton, Jake Runestad, Eric Whitacre, and Samuel Barber–also William Byrd. The program advised that the listed order was subject to change and that there would be improvisations by Gjello interspersed among the other works. Since the approximately hour and fifteen minutes duration of Prom was filled with continuous music and the program said that the order listed was not necessarily the order in which works would be performed, it was difficult to tell exactly what one was hearing at any one point of the performance. There were hints, of course: For instance Caroline Shaw’s piece and the swallows was presented with “a new violin solo by Christopher Moore.” So when there was a violinist standing in the midst of the singers, one could have probably safely assume that one was hearing the Shaw (the program did not list the names of the members of the Carducci Quartet, so one might have assumed that Chistopher Moore was the person playing–in fact it was Matthew Denton, the quartet’s first violinist–that information the product of later research). The harpist, Ruby Aspinall, played only in one piece near the end; that might have been the Panufnik’s Floral Tribute, setting a poem by Poet Laureate Simon Armitage in tribute to Queen Elizabeth II (just guessing, since maybe the fact that it was the commissioned piece would justify bringing in one player for only that piece). It was clear that the end of the program was the Barber, the choral version of Adagio for Strings as an Agnus Dei, which was played by the Carduccis and sung by VOCES8. There was also, over the whole length of the performance, a rather elaborate light show, which this listener did not find soothing, since it made the program hard to read and made it even more difficult to figure out where one might have been in the program. The answer provided by the evidence of the concert to the question “what is mindful mix” though was, apparently, “easy listening.”

Despite complaints, it was clear immediately and through the duration that the playing and singing was really first class and really beautiful and one could be very mindful of and thankful for that.

The Prom on August 8 was presented by the BBC National Orchestra of Wales and the London Symphony Chorus upper voices, conducted by Jaime Martin. The major work on the first half of the concert was the Violin Concerto by Grace Williams, with soloist Geneva Lewis, which was receiving its first Proms performance. The work is in three movements and last about half an hour. It is filled with rhapsodic music which features very clear and compelling long lines. Its orchestration is clear and rich and varied, and the writing for the soloist is very effective. Its tempo and texture over the three movements, though, is very unvaried, so that, in the end, there’s very little differentiation at all, and this listener, anyway, was unable to remember any point in the piece more than any other point, or follow any sort of argument, despite the beauty and effectiveness of any one of the moments. It was preceded in the concert by an Overture, written in 1919 by Dora Pejačević, a composer I’d never heard of before, who is being featured on this year’s Proms, in observance of the centennial of her death. A member of the Hungarian and Croatian aristocracy, Pejačević, according to the program “resolutely rejected an easy path for herself” and pursed a career as a composer (she is said to be the first Croatian composer to write a piano concerto). The overture is lively and appealing and makes one eager to hear more or her music. The language and orchestration are not too far away from that of Holst’s The Planets, written two years earlier, which was the second half of the concert. The audience, which packed out the house, was clearly there for the Holst, and they applauded and cheered loudly and lustily and long after every movement. There was some good reason for this, as the performance was tremendous, as were the performance of the other two pieces.

These Proms and all the others can be heard at https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/series/m001nh6k

I don’t know when else you’d have a chance to see expert musicians interact with a sculpture by one of the most iconic American artists of the 20th century. This rare event, on August 20 at the Dimenna Center in New York, is part of the annual TIME:SPANS festival.

In Earle Brown’s Calder Piece the artist’s mobile is an essential part of the piece. The artwork will “conduct” the Talujon Percussion Quartet as its sections sway from their pivot points. And, yes, you will also get to see the instrumentalists “play” the sculpture, though the artist himself initially expected a more forceful display. “I thought that you were going to hit it much harder—with hammers,” said Calder after the first performance in the early 1960s.

Calder Piece is “the focal point and central hinge of this year’s festival,” according to the introduction in the festival booklet by Thomas Fichter and Marybeth Sollins, executive director and trustee respectively of The Earle Brown Music Foundation Charitable Trust which produces and presents TIME:SPANS. But it is by no means the only highlight of the dozen concerts in the festival.

Talea Ensemble, JACK Quartet, International Contemporary Ensemble, Argento…..once again, since 2015, some of the most acclaimed contemporary music ensembles in the country descend on the Dimenna Center for this late summer aural spectacle. Performances are nearly every night August 12 – 26, chock full of 21st century concert music in a myriad of styles.

It seems almost impossible to pick out highlights from the dozen performances – there are so many intriguing programs. In addition to the Calder event, here are a few that I am particularly looking forward to:

JACK Quartet playing Helmut Lachenmann (August 13) – my mind was blown the first time I heard Lachenmann’s music performed live. He calls his compositions musique concrète instrumentale, creating other-worldly sounds through extended techniques.

Ekmeles performing Taylor Brook, Hannah Kendall and Christopher Trapani (August 22) – though vocal music isn’t my first choice genre, I am drawn to a cappella ensembles, especially when they are as high quality as Ekmeles. Trapani’s music is always a treat to hear, and his End Words lives alongside music by the equally deserving Kendall and Brook.

Ensemble Signal’s program on August 15 is brought to you by the letter “A”: music by Anahita Abbasi, Augusta Read Thomas. Aida Shirazi, Agata Zubel. I’ve been following Abbasi ever since she won an ASCAP composer award about eight years ago. Her music, though not always easy to listen to, is intense and visceral. I predict it will be a great contrast to Read Thomas’s more tuneful style.

Information and tickets at https://timespans.org/program/

Festival of Contemporary Music

Chamber Music

Sunday, July 30, 2023

LENOX – There were a number of firsts on the July 30th chamber music concert. I have never seen the stage at Ozawa Hall require several minutes of vacuuming up bits of wood, but Malin Bång’s Arching, for amplified cello, amplified tools, and electronics, created considerable, if entertaining, mayhem. Another first: hearing “The Wheels on the Bus Go Round and Round,” paired in fugal counterpoint with the Brahms lullaby.

The find for me at FCM was Tebogo Monnakgotla, a Swedish composer who curated Sunday’s concert. The aforementioned nursery rhythm fugue was from her considerably charming piece, Toys, or the Wonderful World of Clara (2008). The backstory: when Monnakgotla’s child was a toddler, she received all manner of musical toys, and loved to run them all at once. The composer recounted that multiple Brahms-singing toys were terribly out of tune, with themselves and each other (this too was incorporated in the piece, in clusters that distressed the lullaby). The idea may have been whimsical, but its deployment was anything but, the piece creating fascinating swaths of texture and crafty quodlibets.

Toys is memorable, but by no means representative of the rest of Monnakgotla’s programmed pieces. Her early Five Pieces for String Trio juxtaposes open cello strings with glissandos, harmonics, and wisps of sul ponticello. The movements cohere into a well-crafted organic whole. Le dormeur du val, a setting of Rimbaud for soprano and mixed chamber ensemble, has a haunting presence. The poem depicts a soldier who appears to be resting near the field of battle. It is only at its very conclusion that we learn of his wounds and realize that he is not resting, but deceased. Monnakgotla employs trumpet calls and vigorous drums to create a bellicose background. The vocal part contrasts this with a feeling of doleful detachment. Soprano Juliet Schlefer did a fine job presenting the ending’s swerve without overselling, and she was equally sensitive when interpreting with the rest of the poem. Schlefer has a lyric voice of considerable beauty: I would love to hear her again.

Two other composers were programmed on the concert. Bent Sørensen’s compact string quartet, The Lady of Lalott, reveled in banshee-like distant howls and prevalent extended techniques. South African composer Andile Khumalo’s solo piano piece Schau-fe[r]n-ster II combines spectralist inflections, with shimmering overtones and chords spaced according to registral positioning in the harmonic series, with second modernist hyper-virtuosity. Joseph Vasconi played the work with adroit facility and a depth of understanding that belied his student status at Tanglewood. Khumalo’s language is distinctive. One presumes and welcomes that we will hear much more from him.

After every one of her pieces, Monnakgotla took to the stage to warmly greet and thank the performers. It was clear that this affection was returned, and that mutual artistic respect played a role in the concert’s success. Tanglewood students at FCM benefit much from the mentorship of senior composers, and it was clear that this collaboration was quite successful.

The concert ended with a reflective piece by Monnakgotla, Companions (seasons) (2021), for solo violin. It represents the various stages of a professional string player’s career as seasons: The ebullient spring of a young student, the prodigy’s successes during a long, hot summer, artistic maturity and the demands of performing and teaching in autumn, and, finally, the winter of retirement, in which the violinist’s instrument is like an old friend. The music is ambitious yet touching, and was played with assuredness and grace by Connor Chaikowsky. A stirring valediction to a memorable concert.

____

On Friday, August 28th, FCM devoted a curated concert to Anna Thorvaldsdottir, an Icelandic composer who is regularly commissioned by some of the best orchestras in the world. The highlights of the concert were two ensemble works, Hrim and Aquilibria, coached and conducted by Stephen Drury, and the closer, the ensemble work Ró, conducted by Agata Zając. Thorvaldsdottir’s music blooms with effervescent overtones, and addresses elements of tonality in novel and frequently surprising ways.

-Christian Carey

Boston Symphony Orchestra, Anna Rakitina, conductor

Joshua Bell, violin

Eliza Bagg, Martha Cluver, and Sonja Dutoit Tengblad, vocalists

July 30, 2023

LENOX – The Boston Symphony’s offerings on the weekend of the annual Festival of Contemporary Music dovetailed with its curation, lifting up female composers and, on Sunday, a conductor. Leading the orchestra on Saturday, July 30th was Anna Rakitina, who has served as the ensemble’s Assistant Conductor until this Summer. She is a rising star and led the orchestra with assuredness, providing detailed interpretations of all of the scores on the program. The orchestra, for their part, were responsive to her gestures, clearly enjoying working with Rakitina and the music on offer. There was a poignancy to the event, as it was the conductor’s last performance with the BSO as Assistant Conductor.

Ellen Reid’s When The World as You’ve Known it Doesn’t Exist (2019) opened the concert. Commissioned by the New York Philharmonic as part of their Project 19 initiative, a series commissioning female composers to celebrate the centenary of the Nineteenth Constitutional Amendment, affording women the right to vote. The piece is diverse in terms of its musical language, and Reid does an admirable job bringing together the disparate strands of its formal design. Vocalists Eliza Bagg, Martha Cluver, and Sonja Dutoit Tengblad are go-to performers for new music with superb voices and vivid musicality. When the World … required them to sing untexted sounds, some playful, others earnestly dramatic. The orchestra frequently responded to the motives in the voices, creating a back and forth dialogue that contextualized the singers’ presence as part of the proceedings. Given the weight of some of the textures over which the singers were required to perform, a bit of amplification would be understandable: the amount used was excessive, adding periodic harshness that the vocalists neither needed nor deserved.

The outer sections of the piece explored fluid textures, with frequent glissandos and vocal ululations, juxtaposed with orchestral tutti. The middle section, a jazzy surprise, introduced a dyadic motive that was then put through a setof variations, including an extraordinary series of long trills near its end. The motive then joined the beginning material to cohere into a beguiling conclusion. Reid is an imaginative composer and excellent orchestrator. One hopes the BSO will commission and program more of her work.

The last time that the BSO played Nicoló Paganini’s Violin Concerto No. 1 at the Shed was in 1987, with Midori as soloist. To have to wait a generation to hear them play it again seems a crime, as it is one of most ebullient and virtuosic of nineteenth century concertos. There was significant recompense, however, in the pairing of violinist Joshua Bell with the orchestra. Bell is one of the most acclaimed soloists active today, erudite and thoughtful as well as bestowed with superlative technical gifts. Bell composed his own cadenzas for the concerto, which were idiomatic, exploratory, and incredibly challenging.

The piece is front-loaded, with the first movement lasting twenty and some minutes. Such was the inspired nature of its performance alone, that there was a vigorous standing ovation before the second movement even began. When it did, Bell played the ardent Adagio’s central melody with poise and gravitas. The final movement is a rondo, with a sprightly theme treated to a technical tour de force of variations. Once again, Bell performed his own cadenzas, which were formidable yet delivered with elan. Once again at its conclusion, the audience greeted Bell and the BSO with a standing ovation. There was no encore: how can you top Paganini?

The second half of the concert was devoted to ten selections from Sergei Prokofiev’s Music from the Ballet Romeo and Juliet, Op. 64. The piece contains some of Prokofiev’s most memorable melodies, its rich orchestration tailor-made for the BSO. Rakitina never allowed the music to be overdone, yet brought out the emotive side of Romeo and Juliet. In its Introduction, she urged the strings to swoon, yet made ample room for woodwind and horn solos. “Montagues and Capulets,” perhaps the hit tune of the work, was given a brisk reading that embodied the crackling intensity of the families’ rivalry. Contrastingly, “The Child Juliet” was rendered with an innocent delicacy that was quite touching. Likewise, a yearning quality imbued the “Balcony Scene” with luminous ardor. “The Death of Tybalt,” in a flurry of activity, was jaunty in its opening and bellicose at its conclusion, percussion and brass providing a roaring climax. The orchestra sounded tremendous here.

“The Death of Juliet” concluded the performance with one of the ballet’s most arresting themes, played caressingly by the violins and buoyed by lower strings, with eloquent utterances from the lower brass and a rejoinder by a chorus of woodwinds. Its stark close, all octaves with sepulchral bass, had more pathos than a minor chord could ever supply. From beginning to end, this was an engaging program.

-Christian Carey

Boston Symphony Orchestra, Dima Slobodeniouk, conductor

Avery Amereau, mezzo-soprano

July 29, 2023

LENOX – This year’s Festival of Contemporary Music at Tanglewood spotlighted female composers. Four created self-curated concerts, and others were featured on BSO concerts. Agata Zubel’s In the Shade of an Unshed Tear, originally composed for the Seattle Symphony, was on the program Saturday night in the Shed. Before its performance, conductor Dima Slobodeniouk talked briefly with Zubel onstage. Prominent among their remarks were the stipulations of the original commission. Seattle was pairing Zubel’s piece with works by Beethoven and wanted her to compose for a classical-sized ensemble, with only timpani for percussion. Slobodeniouk pointed out that new pieces in Europe are generally for a much larger orchestra. Zubel acknowledged that the commission was a challenge.

With In the Shade of an Unshed Tear, the composer rose to the challenge. The timpani began the piece with thunderous attacks, the orchestra following in kind, creating a fortissimo sound that tested the boundaries of a classical-sized ensemble. Zubel employed glissandos grouped among the strings at a lower dynamic level. Still, the fortissimo material seemed inevitable to win out. In a swerve, a denouement followed by the timpani playing pianissimo proved an interesting and organic ending.

Olivier Messiaen’s Les Offrandes oubliêes is a relatively early piece. It is surprising how much of the composer’s musical language was in place by the time he was in his twenties. An ascending mixed-interval scale serves as the principal theme. At the time, the composer was studying Rite of Spring and this is reflected in more rigorous passages that contrast the beguiling melodic ascent.

Mezzo-soprano Isabel Leonard was indisposed and Avery Amereau substituted for her as the soloist in Hector Berlioz’s Les nuits d’été. With a beautiful, round tone throughout all registers from chest voice to high notes, Amereau’s voice was well-suited to the considerable demands of Berlioz’s half-hour long song cycle. Slobodeniouk and she had a few mild coordination challenges, but these were well worth the flexibility of their interpretation.

Maurice Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloé, Suite No. 2 is one of the composer’s finest orchestra pieces. Orchestrated with a deft hand for colorful, abundant contrasts, it encompasses sequences of delicate impressionist harmonies and neoclassical dancing rhythms, with powerful swells at climatic moments that bring the whole orchestra to bear. Slobodeniouk conducted the BSO with verve, urging them to make the most of tutti crescendos while also making ample room for solo passages. The orchestra played with precision throughout and abandon whenever appropriate. It was a satisfying, frequently inspiring evening.

- Christian Carey

Hanns Eisler’s biography might be better known than his music, at least on this side of the Atlantic. Born in 1898, he was German/Austrian, half-Jewish, a committed student of Schoenberg, and a staunch communist. He maintained a lifelong collaboration with Brecht, and like the latter, fled the Nazis for America in the 1930s, where he took up shop in Hollywood, composing well-regarded scores for numerous minor films before being hounded out of the US by post-War anti-communist hysteria. He ended up resettling in the short-lived and little-missed Deutsche Demokratische Republik (East Germany) whose national anthem he penned while languishing under the yoke of Soviet-bloc artistic and political oppression. He died there in 1962.

Hanns Eisler’s biography might be better known than his music, at least on this side of the Atlantic. Born in 1898, he was German/Austrian, half-Jewish, a committed student of Schoenberg, and a staunch communist. He maintained a lifelong collaboration with Brecht, and like the latter, fled the Nazis for America in the 1930s, where he took up shop in Hollywood, composing well-regarded scores for numerous minor films before being hounded out of the US by post-War anti-communist hysteria. He ended up resettling in the short-lived and little-missed Deutsche Demokratische Republik (East Germany) whose national anthem he penned while languishing under the yoke of Soviet-bloc artistic and political oppression. He died there in 1962.

Eisler’s 125th anniversary this month, coupled with a new recording of his magnum opus, the Deutsche Sinfonie, provides an opportunity to revisit the legacy of this controversial musician, a task facilitated by Brilliant Classics’ ten-CD Hanns Eisler Edition, released in 2014 and featuring several generations of eastern German recordings, many of them originally issued on the Berlin Classics label. Eisler’s life and career followed a similar path to Kurt Weill’s through the latter’s premature death in 1950, and indeed the conventional wisdom tends to regard Eisler as a poor man’s Weill. Traversing these recordings for the first time in several years leads me to conclude that in this particular case, the conventional wisdom is pretty accurate.

Aside from his film scores, Eisler is best remembered for his many Brecht settings, ranging from simple lieder for voice and piano, through cabaret-style theatrical works using a small orchestra, on up to full-fledged martial protest songs for chorus and instruments. The essence of Eisler is the genre of cynical but tuneful cabaret song that’s closely associated with Weill. CD 6 of Hanns Eisler Edition features Gisela May’s classic renditions of many of these songs, and hearing her is a genuine treat. Her clear diction, appropriate use of sprechgesang, and obvious enthusiasm for the material come bubbling through, and the reworked sound of these recordings, mostly from the 1960s, is better than one might expect from a budget label. Among May’s interpretations is the anti-war song O Fallada, da du hangest, which refers to the Goose Girl story recounted by the Brothers Grimm.

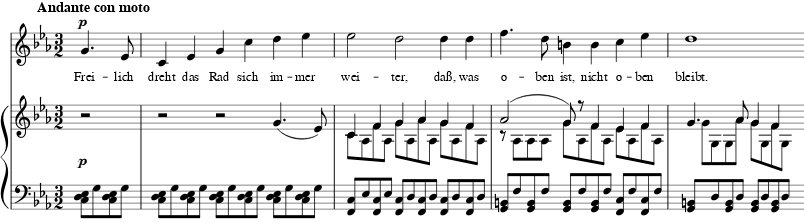

CD 7 conveys a generous dose of old Irmgard Arnold tracks as she works her way through the Hollywood Liederbuch. After this come a few tracks with Eisler himself singing songs like Die Ballade vom Wasserrad (a kind of Brechtian Gretchen am Spinnrade).

Some of the most poignant of Eisler’s songs are his late Brecht settings: post-Holocaust poems like In the flower garden. Many others, such as the selections from Die Rundköpfe und die Spitzköpfe (Round Heads and Pointy Heads) are pretty indistinguishable from Weill’s brand of modernist-tinged cabaret, right down to the working class “pit combo” ensemble. Complementing this instrumentation are the many settings for voice and piano. Eisler may have been one of the very last composers to contribute meaningfully to the Romantic art song for this combination, a genre that has since become ossified and moribund.

After landing in the DDR, Eisler’s music got a lot more didactic and tonal. Mitte des Jahrhunderts (Middle of the Century, dating, appropriately enough, from 1950) is heard on CD 9, and it’s a good example of the simplified style. It’s a choral cantata with an interposed orchestral Etude that sounds more like Prokofiev than Weill. CD 10 continues the trend, focusing on choral arrangements of moralizing songs, including a few of Eisler’s most famous agitprop specimens, which to be sure, often originated in the 1930s. One thing Eisler did get out of his stint as DDR’s most internationally prestigious composer (most of his eminent colleagues having long since fled to the West) was the material support of the Communist regime in making these recordings. Aside from the East German national anthem (Auferstanden aus Ruinen, inexplicably omitted from Brilliant’s collection) Eisler’s most famous tune is probably his setting of Brecht’s Und weil der Mensch ein Mensch ist (AKA United Front Song) with its characteristic refrain “Drum links, zwei, drei”. CD 10 (and the set) concludes with a suitably militaristic choral rendition of it. The irony of deploying march rhythms and unison singing in the service of ostensibly anti-authoritarian texts is self-evident. And whereas Eisler’s Weimar-era kampfmusik used instrumental combos and ragtime/jazz-influenced rhythms to connote underclass origins, the effect here is more evocative of a frenzied mob or struggle session.

CD 10 also includes a handful of English-language performances, such as From Narrow Streets and Hidden Places and The Flame of Reason.

So much for the stereotypical Eisler. What’s striking to me, though, is how much instrumental music he left us. Brilliant Classics includes much of it here, mainly suites arranged by the composer from his many film and stage scores. These are a delight to listen to, both because they’re unfamiliar and because they’re more harmonically advanced than his better-known vocal works. Eisler’s Hollywood scores are particularly obscure today because they mainly went into films that did not become classics. The lively Nonet No. 2, culled from his music for the 1941 film The Forgotten Village (itself a curious example of ethnofiction, with a voice over written by John Steinbeck) is characteristic of this style, which shares a common lineage with early Hindemith (e.g., his Kammermusik No. 2 from 1925).

It’s in these works that Eisler’s debt to Schoenberg comes through most vividly. Vierzehn Arten den Regen zu beschreiben (Fourteen Ways to Describe the Rain), composed for a Joris Ivens film, recalls Schoenberg’s Suite, Op. 29, but benefits from Eisler’s penchant for solo winds and open textures (by contrast with Schoenberg’s frequently turgid orchestration). It’s worth recalling that Weill’s earliest canonical music is also heavily indebted to Schoenberg, and many of Eisler pieces for mixed chamber ensemble bear a close resemblance to the sound world of Weill’s youthful Violin Concerto.

CD 8 features solo piano music from the 1920s, closely modeled after Schoenberg’s groundbreaking Op. 19/23/25 pieces. Many compositions in this style emerged from the interwar Germanosphere, but Eisler’s are among the best that weren’t written by Schoenberg, Berg or Webern. This music delights in its unabashed atonality, shorn of the constraints of functional harmony like a nudist shorn of uncomfortable clothes. It occasionally suffers from the same rhythmic rigidity that disfigures much of Schoenberg’s serial music: endless bars of 2/4, 3/4 and 4/4 time with steady eighth notes.

A mid-century German Symphony?

Most of Eisler’s works are miniatures or collections of miniatures. And they tend to be repetitive forms like strophic songs or variation sets (c.f., the aforementioned Vierzehn Arten). Eisler seemed most comfortable in short formats, relying on brief characteristic musical gestures, and an ever-vibrant range of instrumental color (hence the eagerness to employ mixed chamber ensembles). There’s one big exception to this though: the Deutsche Sinfonie, Eisler’s most musically ambitious and distended work. It occupies all of CD 3 in Brilliant Classics’ set in a 1974 recording that features multiple East Berlin musicians under Max Pommer, and is also available in a 1989 live performance featuring Günther Theuring and the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra that’s just been released by Capriccio (an Austrian label specializing in lesser-known European modernist works such as Henze’s Das verratene Meer, Schulhoff’s Flammen and Wellesz’s The Sacrifice of the Prisoner).

Basically, the Sinfonie is an 11 movement oratorio for soloists, speaker, chorus and orchestra. It lasts over an hour, setting several anti-fascist texts by Brecht and one by the Italian novelist Ignazio Silone. Its sound world is comparable to Schoenberg’s Jacob’s Ladder or A Survivor from Warsaw as they might have been adapted by Weill and Brecht. Originally composed in 1935 and 1936, with new movements added as late as 1957, the Sinfonie is “full of political warning to the German people and to those Communists in lock-step with Moscow” as Steve Schwartz puts it. Several of Brecht’s texts tell of German concentration camps, which it’s worth remembering were first opened in 1933, well before Kristallnacht.

Eisler’s works don’t rise above the agitprop as well as Weill’s, and Deutsche Sinfonie can seem as preachy as the most sycophantic cantatas of Shostakovich and Prokofiev. Nevertheless it’s one of his most musically compelling works, containing many fascinating and unnerving moments. It seems to be a precursor to works like Henze’s 9th Symphony, and probably deserves to be more widely heard, at least on disc.

The Sinfonie‘s Praeludium opens with a slow mournful theme entrusted to the violas, kind of a twelve-tone echo of Mahler’s 10th Symphony.

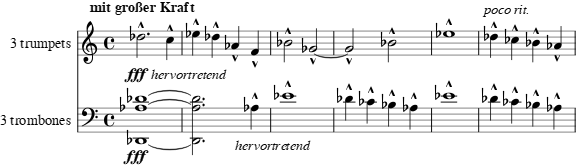

A bit of worldly buildup and subsidence sets the stage for the chorus’s entry: a homophonic setting of verses from Brecht’s Germany (Oh Deutschland, bleiche Mutter! Wie bist du besudelt, meaning “Oh Germany, pale mother, how you sit defiled”). The quotation of the Internationale in the trumpets at 4:50 is obvious to anyone who still recognizes that tune. Less familiar nowadays is its counterpoint in the trombones, which quotes a lament for the martyrs of the 1905 Russian Revolution that became known in German as Unsterbliche Opfer (Immortal Victims) and which is also quoted in Hartmann’s Concerto Funèbre and Shostakovich’s 11th Symphony.

All but the last of the Sinfonie‘s movements are twelve-tone, displaying Eisler’s characteristic implementation which emphasizes traditional tonal relationships and the facile extraction of short riffs. A good example of the latter is in the second movement, Brecht’s To the fighters in the concentration camps, a passacaglia over a ground constructed from two pairs of repeated half-steps (which in turn spell out a transposition of the famous B-A-C-H motif). Brecht’s poem features the notable line Verschwunden aber Nicht vergessen (“gone but not forgotten”).

Next up is the first orchestral interlude, called Etude 1. Eisler appropriated this lively movement from the finale to his Orchestral Suite No. 1 (track 4 on CD 1). It leads directly into Brecht’s Erinnerung (Remembrance), commemorating a suppressed anti-war demonstration in Potsdam. It’s set as a kind of post-Mahlerian funeral march. Next comes In Sonnenburg, named after one of the Nazi’s first internment camps. In the 1958 published edition from Breitkopf & Härtel this is cast as a baritone solo, but both Pommer and Theuring do it as an alternating duet between soprano and baritone soloists. On the word leer (“empty”) in ihre blutigen Hände aber immer noch leer sind (“their bloody hands are still empty”) the singer is instructed to perform a fascist salute.

The second orchestral interlude, Etude 2, follows. It appears to have been originally composed for this piece, and is in two broad sections: slow-fast. The main motivic idea is two descending major thirds separated by a minor second (e.g., D♯-B-D-B♭), an idea also foregrounded in the second movement. Movement 7 is Burial of the Troublemaker in a Zinc Coffin, the “troublemaker” being a worker demanding to be paid his wages and be treated as a human being. The chorus dramatically personifies the compliant mob with “He was a troublemaker. Bury him! Bury him!”. Male and female soloists are heard here too, lending the movement quite a bit of coloristic variety. Like several of the other movements, this one frequently has a martial feel to it. After the choral admonition that “whoever proclaims their solidarity with the oppressed will be put into a zinc box like this one”, the movement ends with another soft and resigned funeral march, this one emphasizing triplet rhythms on the first and second beat.

Next up is a four-part cantata-within-an-oratorio, appropriately called Peasant Cantata. It’s the only movement with a non-Brecht text, excerpted from Silone’s 1936 novel Bread and Wine (which the US surreptitiously disseminated among Italian partisans to gin up anti-Mussolini support during WW2). It too opens with march rhythms. Part three uses two male speakers accompanied by strings and soft humming in the women’s chorus. The fourth part is yet another march.

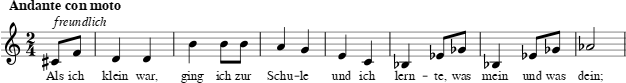

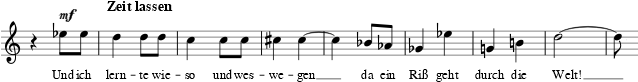

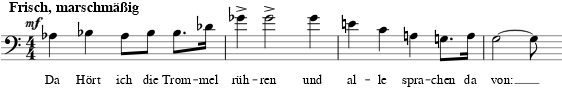

The movements have been getting longer and more complex as we go on, and at 15 minutes, the Worker Cantata (AKA Das Lied vom Klassenfeind or Song of the Class Enemy) is the longest individual movement in all of Hanns Eisler Edition. At last the composer puts forth an extended organic structure, melding stanza form with elements of traditional sonata form. After an orchestral introduction, the mezzo-soprano delivers what sounds like a strophic song, with a folk-like, though serial, melody in straightforward 2/4 time.

The continuation descends stepwise.

After two statements of this comes a new idea, one of those jaunty workers’ marches harkening back to Eisler’s Weimar days. The text here is passed to the baritone who sings a new tune, but then ends with the same continuation theme as the soprano.

An orchestral passage recalls the march and leads to a climax after which (at 5:29) comes one of the Sinfonie‘s most effective moments: a soft kettledrum roll on low A♭ providing the sole accompaniment for the choir as they dramatically enter with a chorale-like setting of “and as the war was about to end”. Some developmental passages follow, climaxing with the mezzo-soprano and baritone soloists singing in octaves (a doubling previously avoided in the Sinfonie). Fragmentation of earlier material in the choir takes us to a scherzo section in 3/4 time (8:26), which features new material and alternation between soloists (still singing in octaves) and chorus.

We arrive back at the march song which, as before, is entrusted to the baritone. An out-of-tempo quasi recitativo passage in the mezzo-soprano leads to the coda, which Eisler launches by having the chorus alternate lines with one of the speakers from the Peasant Cantata. The apogee comes with a repetition of the march idea with the chorus delivering the closing line “and the class enemy is the enemy”.

Movement 10 is the last of the orchestral interludes. Originally conceived as the finale, it’s of also extended length (nearly ten minutes, making it one of the longest instrumental tracks in the collection), using a structure that approximates sonata form. We start right out in allegro 3/4 time. After some introductory bars, a low string ostinato sets in, over which the main theme is stated by a solo horn (at 0:25). If it sounds vaguely familiar it’s because it uses the same row as the viola melody that opens the Praeludium. The first trumpet immediately inverts the tune, and later the violins restate it in its original shape. The tempo slackens for the second theme, heard in clarinets in thirds (at 1:50). Sudden timpani strokes (4:23) herald a change to duple time. At 5:09 Eisler returns to triple time, and starts to develop the first theme, in both original and inverted form as before. At 6:10, the trumpet develops the second theme in canon with the horns. The meter continues to switch between duple and triple, and the development become more fragmentary and the texture thinner until we’re left with an accompanied cadenza for solo violin. The coda reprises the main theme and its dotted rhythm amid multiple layers of crescendo’ing counterpoint, leading to a conclusion which, while not exactly triumphant, is rather more upbeat than most of what we’ve heard before. I personally find the mood of this movement a bit out of character with the rest of the sprawling Sinfonie, despite its motivic integration. An interesting detail reported by David Drew is that the three orchestral movements make up a sort of symphony within the oratorio, with Etude No. 2 taking the role of both scherzo and slow movement.

The work ends with a surprisingly brief choral Epilog, little more than a fragment built atop an A-E♭-F♯ ostinato in the low strings that underpins Brecht’s “this is what you get” lament for the German war dead (the complete text in German is Seht unsre Söhne, taub und blutbefleckt vom eingefrornen Tank hier losgeschnallt! Ach, selbst der Wolf braucht, der die Zähne bleckt, ein Schlupfloch! Wärmt sie, es ist ihnen kalt! Seht unsre Söhne, the key words meaning “See our sons”). This movement was tacked on in 1957, years “after the fact” on the occasion of the work’s publication and full premiere. It’s actually an arrangement of the introduction to Eisler’s cantata Bilder aus der Kriegsfibel, which is heard on CD 9. In its resigned ambiguity it seems to sum up the despair Eisler must have felt toward the end of his life, when so many of his personal and ideological dreams lay shattered. Indeed the compositional history of the Deutsche Sinfonie is itself a microcosm of Eisler’s plight: composed mainly in exile, unperformable in Germany during the Nazi era, and upon Eisler’s return promptly suppressed by communist censors for its Schoenbergian atonality in keeping with the Soviet-imposed dogma that Eisler himself had helped promulgate through his enthusiastic endorsement of the Zhdanov doctrine at the 1948 International Congress of Composers in Prague—a cautionary precedent to today’s bilateral attacks on artistic and academic freedom.

Thanks to a modest cultural liberalization in 1958 the work was finally unveiled, but by that time Brecht was dead and the basic anti-Nazi message was no longer as topical.

Risen from the ruins?

Eisler’s music may not be of the same caliber as Schoenberg’s or Weill’s, but it’s good enough to repay the time spent listening through these recordings. As with most Brilliant Classics releases, Hanns Eisler Edition comes with a few cut corners, notably the lack of song texts and translations. But you do get extensive program notes by Günter Mayer (which can be downloaded, along with track listings, from Brilliant’s Web site). And the budget price certainly makes it a compelling purchase for almost anyone interested in 20th century music—at least if you’re able to approach Eisler’s didacticism in the same spirit that freethinkers are obliged to employ when appreciating musical settings of religious texts. Spend a couple weeks with the Eisler oeuvre, then go on to Brilliant’ Paul Dessau Edition and the new recording of Dessau’s Lanzelot to complete your tour of the DDR’s musical mini-heyday.

Orlando Consort

Machaut: The Fount of Grace

Hyperion Records

Matthew Venner, countertenor; Mark Dobell and Angus Smith, tenors; Donald Greig, baritone

Guilliame de Machaut (1300-1377) was a supremely talented poet and composer. He was an innovator, creating the first polyphonic Mass and developing polyphony in chansons as well. After Machaut, there is little evidence of composers in the Medieval era who set their own words to music. Works devoted to courtly love make up the majority of his output. Fount of Grace adds several topics to that of love poems: devotional and historial components loom larger than on other recordings of Machaut by Orlando Consort.

After thirty-five years, Orlando Consort gave their last performance on June 7, 2023. The Fount of Grace is the tenth of eleven recordings of Orlando’s survey of Machaut. The title references a name for the Virgin Mary, to whom some of the programmed works offer devotions, explicitly or in a veiled fashion.

Le lay de la fonteinne is the most overtly religious, petitioning the Blessed Virgin for love and grace. Like traditional lays, the rhythm scheme and melodic framework are complex, with different rhythms and melodies in each couplet, apart from the first and last, which provide a refrain to begin and end the piece. Odd-numbered lines are monophonic, while even-numbered lines are performed as three voice unison canons; a reference to the trinity that, late in the piece, is supported by an evocation of its formula. The singing of the canons is quite beautiful, with the overlapped lines delivered with clear diction and vivacious rhythms. At over twenty-four minutes in duration, it is by far the program’s longest work and, thematically, its centerpiece.

Machaut also references occurrences of his day, a particularly fraught time in France, beleaguered with plague, pestilence, and the Hundred Year’s War, which at the time of these compositions was going quite badly for the French. The motet Tu qui gregem/plange regni/Apprehende arma is an example. It references taking up arms against the foe at a point during the Hundred Years War when the nobles of France were in desperate straits, with some taken hostage by the English forces. Likewise, Christe qui lux/Veni creator spiritus/Tribulatio proxima est implores Christ to be with those in danger. The counterpoint, which includes canonic and free passages, is finely knit, with upper voices Matthew Venner and Mark Dobell leading off the proceedings with an ardent duo that, soon enough, is accompanied by the other voices in fascinating overlapping relations. The ballade Donne Signeurs, urges noblemen to be good to their subjects. A sustained tune sung by tenor Angus Smith, an upper register melody performed by Venner, and harmonies incorporated by the other vocalists, with a sonorous bass line by Donald Greig, create a fascinating, vibrating texture.

Courtly love is not neglected on the program. Two versions of the Rondeau Tant doucement me sens emprisonnez are included, one for two voices and the other four. The theme of being imprisoned by love is a venerable one among chansons, and this text expresses it well. The duet’s two voices move at different rates, with a fetching melismatic top voice. The quartet is even more varied in rhythmic activity. With Tant doucement … Machaut creates a tour-de-force times two in the chanson genre.

The Orlando Consort still sound in fine voice and will be sorely missed. At least we have one more Machaut recording to which to look forward.

-Christian Carey

Manchester Collective

Neon

Bedroom Community

Alex Jakeman, Flute; Oliver Pashley, Clarinet; Rakhi Singh, Violin;

Hannah Roberts, Cello; Beibei Wang, Vibraphone; Katherine Tinker, Piano

Manchester Collective’s fourth recording, Neon, includes totemic pieces by Steve Reich and Julius Eastman, as well as works by Hannah Peel and the first concert music composition by Lyra Pramuk. It is a well-considered and excellently performed program.

The centerpiece is Steve Reich’s Double Sextet, a work for two “Pierrot plus Percussion” ensembles that won the 2009 Pulitzer Prize. The piece can either be performed live by twelve musicians or by a single sextet against an overdubbed rendition of the second grouping. Manchester Collective opts for the latter. The performance is so tight that the lines between live and recorded are erased. This is due in no small part to the energetic and laser beam focused playing of violinist Rakhi Singh and cellist Hannah Roberts. Double Sextet is one of the best of Reich’s later compositions and this performance is a welcome addition to his recording catalog.

Julius Eastman’s “Joy Boy” begins with vocal improvisations that display a surprisingly Reich-like harmony. Pitched percussion and repeated ululations bring the performance to a cadence point, after which the instruments vie for dominance in the texture. The second section is based on just a few harmonies, but their elongation and the sudden eruptions that periodically occur keep things interesting.

In an affectionate homage, Hannah Peel tropes ideas and sounds from Steve Reich in the recording’s title piece. We are treated to some flavors reminiscent of Double Sextet, but also samples from Shinjuku train station, a nod, albeit a far less angsty one, to Reich’s Different Trains. Peel is expert at bringing together these disparate strands. The first movement, “Shinjuku,” is ostinato filled and brightly hued. The second movement, “Born of Breath,” has some lovely clarinet writing for Oliver Pashley, a fine player with excellent control of limpid runs and upper register forays. Flutist Alex Jakeman is compelling too. Here she contributes shorter lines, often dramatic in the timing of their appearances. Less minimal in design than the other movements, it has a beguiling ambience. The finale, “Vanishing,” features vibraphone and piano, played with keen attention to dynamic shadings by Beibei Wang and Katherine Tinker, with repeated patternings from the rest of the group coalescing into a lovely surface.

Lyra Pramuk produced Neon and, encouraged by the group, tried her hand at creating a composition for them. A producer, vocalist, performance artist, and composer of electronica, it is not surprising that she excels in adding another component to her polyartist career. Of her work Quanta, she says, “There is no universal time. Quanta explores the notion that each of us has an individual sense of how time traces through our lives.”

The ticking of a grandfather clock opens the piece, at first keeping strict time, then devolving into varying tempos, and finally stopping. Sustained tones emerge from the grandfather clock’s ticking, followed by a diatonic duet for clarinet and cello. Shimmering vibraphone announces the return of the rest of the ensemble, playing extended triadic harmonies to accompany successive solos from each of the wind and string players. The language is lush, with overlapping lines from the entire group creating a tapestry of interwoven melody. The next section adds flute trills, glissandos, and pizzicato to further enhance the texture. A long decrescendo compresses the material until it vanishes. Pramuk’s Opus 1 suggests she should add more concert music to her resume.

Neon features a thoroughly engaging program and talented ensemble. Recommended.

-Christian Carey