| DARON

HAGEN IN THE DOCK

An exchange

about "Vera of Las Vegas" between Russell Platt, from The New Yorker and

Daron Hagen, composer of Vera of Las Vegas

Russell

Platt: This is your third opera written in collaboration with Paul

Muldoon.

How did it all start-and what makes it work?

Daron

Hagen: Paul and I had just finished the long process of following

Shining

Brow from composition through production when the University of

Nevada

Las Vegas Opera Theater asked us for a new opera on a subject of our

choosing.

Having just created a very large, traditionally-crafted theater piece,

we wanted to let our imaginations run wild, try to make words and music

work together in new ways. Textually, the libretto rings changes on a sprawling

sestina. Paul calls it the verse-vehicle for the serendipitous.

Musically,

the score is a series of variations on a rhythmic and motivic cell. Wedded

to these two very powerful forms, the words and music could move forward

like a mad juggernaut, seemingly "all over the place" but always tightly

controlled.

RP:

You've also written a fair number of songs to his poetry. How is setting

a

Muldoon libretto different from setting a poem?

DH:

Paul and I co-write filmic treatments for our projects, then Paul writes

the words for a scene, and I set it to music, making changes to the words

when necessary. On the telephone, by email, or by fax, I then show him

the changes and he lets me know when he thinks I've harmed the literary

viability

of the words. Since I approach his words with admiration and delight, this

is extremely rare. When I set Paul's poetry, I don't even consider altering

the words, since they were conceived from the outset by Paul as poetry,

not as libretto.

RP:

Your opera was commissioned by the University of Nevada at Las Vegas,

for

performance by the forces of its Opera Theatre program. I assume that

they

knew that they were getting an opera that would be Vegas-centered-but

were

they shocked by what the opera turned out to be? Vegas is not exactly a

prudish

town, but still.....

DH:

They didn't know what the opera was going to be about and, living in

Vegas

as most of the cast and production team did, weren't at all shocked by

the

subject matter. A theater piece is like a sailing ship, an ungainly mass

of

lines and sail when docked, but gorgeous and graceful (or not) when doing

what

it was built for. This piece is so complex that we elected to forgo

staging

in Las Vegas and cut a cast album instead, use that recording to

gather

support for the piece, and then have it staged professionally - hopefully

in New York. Audiences were invited to attend what were described as "open

recording sessions" which probably mystified them.

The

fact that the character of Vera is a transvestite prompted several rather

nasty

messages

about where I was likely to spend eternity on my hotel voice mail

from

people (men) who didn't identify themselves.

RP:

We can read from the synopsis that this is a work about a couple of

not-so-bright

IRA journeymen who wander into a trap-a many-sided vortex, really-in Las

Vegas. But what else is it about?

DH:

The opera is still teaching Paul and me what it is about: transformation,

the relationship between appearance and reality, the horror of terrorism,

and the state of extremis - all of these things, but so much more. Naturally,

Vera makes more "sense" when it is staged, but it is also

a

lot more fun, scarier, and sexier. For example, it is one thing to read

in

the

liner notes that Taco is being interrogated at the beginning of the

opera,

but quite another to witness it - the blows, the blood, the cries of

pain.

It's one thing to hear a chorus of strippers sing to their customers

and

quite another to see them do it while they're dancing. Charles Maryan,

our

stage director, tells us that what we've really written is a shooting script

- we were thrilled to hear that - and that he's been staging it as such.

RP:

I think, despite the commonness of the subject matter, that there is

something

compellingly noble, even heroic about this piece that you and Paul

have

written-it's not just verismo, slice-of-life type stuff. Am I on to something?

DH:

I think that you cut to the core of the piece. Words and music create a

bridge

between the audience and the characters in the opera: Taco and Dumdum

are

murderers, Vera's a transvestite, Doll's a spy. Not necessarily people

one would want to spend an evening with. Or not? Paul mentions that,

in Northern Ireland, "appearance and reality are extremely difficult to

establish, and an expert on the tragedies of Euripides may turn out to

be a trigger puller." Life is Art, Art is Life. But Rotten people

can make great

Art,

and Great people can make rotten Art. Good people can do terrible things;

terrible people can do good things. The important thing in this opera is

that all the characters, despite their baggage, are attempting to transform

themselves into something better than they are, and we, as audience members,

can't help hoping that they'll succeed. That transaction ennobles us all,

gives us hope amid the wreckage.

RP:

Eclecticism seems more fashionable than ever before, but it strikes me

that

the two of you have very different notions of what variety in art can

mean.

Paul has this wizardly way of finding different spins for a well-worn group

of words-like bar, horn, strip, or lemon, just to name a few in this libretto-that

seem to drive the libretto along as much as the "plot" or the characters'

urges or intentions.

You

however, are a flagrant (if you'll allow me) polystylist-we've got tonal

classical music here, in addition to jazz, Broadway, 70's folk rock, intellectually

organized chromatic music, and more. Do you try to make a kind of "sense"

of Paul's virtuoso wordplay-a kind of musical correspondence, if you will-or

just go with your own sense of flow?

DH:

What strikes you as polystylist is to me the spinning of "well-worn groups

of notes" just as Paul does when he spins "well-worn groups of words."

The words and music are up to exactly the same flagrant mischief.

RP:

After Mozart, music history seems to be divided between composers who write

operas and those who write just about everything else. But you do both,

having also written a copious amount of orchestral music, chamber music,

band music, choruses, songs. Do you feel apart from the pack, or part of

a new wave?

DH:

I went my own way a few years ago and am not really aware of who, among

the composers I grew up with during the eighties and nineties, has written

what or for whom for the past ten years. I don't even know who is a member

of the pack now, let alone where it is heading! I listen carefully to new

works by composers who are old friends, to my students' new pieces, and

to the recordings and scores that young composers send me. I don't

listen to my own music. Writing music, learning it to perform it as a pianist

or to conduct it takes whatever musical energy I seem to have.

RP:

Are the processes different in anyway, or is dramatic music just another

form of music coming out of your head? How do dramatic forms and abstract

forms differ in the compositional process?

DH:

I have been trying to make my instrumental (so-called "pure" music) more

like my vocal music and vice versa. I've never differentiated in my own

mind between so-called "abstract" music and "dramatic" music. Music in

itself is an abstract art form. When music is tied to words it seems to

me to become even more enigmatic because what is one to do when setting

a word like "rheumatism" for example? It is a beautiful mouthful of a word

to sing and to set, but as I have it, I know firsthand that it is unpleasant

to have. Shall I set the word to "painful" music? What is painful

music? Or shall I set the delicious sound of the word to "delicious" music?

Madness!

RP:

You've acknowledged Ned Rorem and Leonard Bernstein as two of your most

influential mentors. On the surface these two seem to have a lot in common,

but they're actually quite fundamentally different: Ned the aristocrat,

Lenny the man of the people. You've written an opera about a "vulgar" subject,

that has all these "vulgar" styles in it, and yet your ord-setting

has

this jewel-like precision to it-like a princess traipsing through mud.

Is this an aspect of your artistic personality-or is it just Vegas? Just

America?

| DH:

I love your image of a princess traipsing through the mud. She must benamed

Vera, of course, and she must embody the Truth. Every character in Vera

sings the way they do because, if I were they, those would be the notes

I would sing. That's what gives the notes their dignity. At a certain point,

you've either found your voice or you haven't. This was how I found mine.

Lenny's been gone for over a decade now; Ned's become an old and treasured

friend. Is Ned really aristocratic? Was Bernstein really a man of the people?

Is the subject of Vera of Las Vegas really vulgar? The truth is that both

are just tremendously gifted, hard working composers trying to reach the

next double bar and that Vera's no more vulgar than a walk down Broadway

on a Saturday afternoon. |

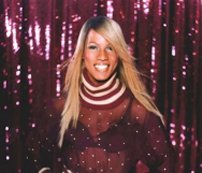

Shequida

as Vera |

(C)

copyright 2003 Burning Sled LLC

|