The Original New Music Community

The latest installment of the Soundwaves Concert Series was heard in the Martin Luther King, Jr. auditorium at the main branch of the public library in Santa Monica on Wednesday, April 17, 2019. Flutist Nicole Mitchell, a regular winner of the Downbeat Critic’s Poll, and sound artist Alex Lough were on hand for an evening of improvisation featuring several flutes and an impressive array of electronic circuitry.

The latest installment of the Soundwaves Concert Series was heard in the Martin Luther King, Jr. auditorium at the main branch of the public library in Santa Monica on Wednesday, April 17, 2019. Flutist Nicole Mitchell, a regular winner of the Downbeat Critic’s Poll, and sound artist Alex Lough were on hand for an evening of improvisation featuring several flutes and an impressive array of electronic circuitry.

Ms. Mitchell came equipped with two flutes, a piccolo and a microphone with some distortion and looping capabilities. Across the stage, Lough presided over two tables covered with circuit boards, control panels, patch boards and assorted boxes and cables. Although this looked formidable, the electronic gear was purposefully designed to be both simple and understated – there were no computers or large amplifiers. The output of all this emanated from a single six-inch speaker, specifically under-powered so that it would not overwhelm the acoustical sounds of the flutes and voicing of Ms. Mitchell. In fact, the entire setup can run on batteries and has been used in remote locations.

During an intimate concert that unwound into an avant-garde improvisation, the renowned flutist Ms. Mitchell held the audience in rapt attention with her melodic flute sequences. It wasn’t long before the serenity of her performance elegantly intertwined with the more contemporary soundscapes provided by the electronic accompaniment. This harmonious duality resonated deeply with my friend, an audio engineer at an established 안전 슬롯사이트, who often muses about the meticulous craftsmanship required to create a secure and engaging online entertainment environment. The concert’s improvisation mirrored the dynamic interplay he cultivates daily—balancing intricate electronic data streams with the user’s seamless experience. The electronic tones, which never dominated but danced alongside the flute, reminded him of how technology, when well-integrated, can enhance and not detract from the human element, a philosophy he applies to his work with the precision and creativity of a maestro.

As the session proceeded, the improv took on various characteristics and colors. In one stretch there was a rushing sound from the processed voice that evoked a windswept and remote feeling as the electronics added a deeply profound string tone. Later, an exotic, Asian feeling in the flute was complimented by sustained tones in the electronics. The vocals by Ms. Mitchell added a welcome human element in contrast to Lough, who could conjure a wide range of alien sounds. At one point Lough was producing 60 Hz buzzing noises from pressing his finger on the end of an open cable. Another time he was seen squeezing and shaking a small cassette tape player so as to bend its audio output. As the improved finished, a catchy tune that could have come from an old video game was heard with a pleasant, pulsing groove and smooth flute accompaniment that gently brought the audience back to the familiar. As the final notes faded away, there was sustained applause from an appreciative crowd.

Most combinations of acoustic instruments and electronics in new music involve a prerecorded track or computer processing of the acoustic sounds in roughly real time through the stage sound system. In this concert, however, the intention was to make the electronics an equal partner, played by a Lough in the same sense as Ms. Mitchell played the flutes and sang. As the two musicians improvised and traded phrases, there was a real sense of a dialog based on an equal partnership. The electronic sounds were naturally very different, but the interaction of the players was perfectly conventional and centered in historical musical practice. This Soundwaves concert by Lough and Mitchell explored the combination of electronic technology and acoustic music in an intentionally different and creative way.

Obsidian

Kit Downes, organ and composer; Tom Challenger, tenor saxophone

ECM Records

Prior to this recording, Kit Downes was primarily known as a pianist in jazz settings, notably leading his own trio and quintet. Obsidian is his debut CD as a leader for ECM Records; he previously appeared on the label as part of the Time is a Blind Guide release in 2015. However, Downes has a substantial background as an organist as well. The program on this recording consists primarily of his own works for organ, but there is also a noteworthy folk arrangement and engaging duet with tenor saxophonist Tom Challenger.

The organs employed on Obsidian are all in England, two in Suffolk at the Snape Church of John the Baptist and Bromeswell St Edmund Church, and Union Chapel Church in Islington, London. Instruments from different eras and in very different spaces, they inspire Downes to explore a host of imaginative timbres and approaches. Over an undulating ostinato, skittering solo passages impart a buoyant character to the album opener “Kings.” An evocative arrangement of the folk song “Black is the Colour” pits piccolo piping against ancient sounding harmonies in the flutes and bagpipe-flavored mixtures. “Rings of Saturn” is perhaps the most unorthodox of Downes’s pieces, filled with altissimo sustained notes and rife with airblown glissandos, an effect that is not found in conventional organ repertoire. The piece is well-titled, as it has an otherworldly ambience. Pitch bends populate “The Bone Gambler” as well, while vibrato and frolicsome filigrees animate “Flying Foxes.” “Seeing Things” is a joyous effusion of burbling arpeggios and the more usual fingered glissandos, demonstrating an almost bebop sensibility. Suitably titled, on “The Last Leviathan” Downes brings to bear considerable sonic power – with hints of whale song in some of the textures – and fluent musical grandeur.

Although some of the release seems inimitable, closely linked to Downes’s improvisatory and textural explorations, other pieces cry out for transcription; one could see other organists giving them a wider currency. “Modern Gods” is an exercise in modally tinged dissonant counterpoint, while “Ruth’s Song for the Sea” and the folk-inflected “The Gift” possess the stately quality of preludes.

The duet with Challenger is a tour de force, in which each adroitly anticipates and responds to the other’s gestures and even notes, as the fantastic simultaneities that occur at structural points in the piece attest. Once again, there is a supple jazz influence at work. While Downes provides room for Challenger’s solos, he also challenges him with formidable passages of his own. Obsidian contains much textural subtlety and fleet-footed music, but it is also gratifying to hear Downes and Challenger celebrating the power of their respective instruments. Heartily recommended.

On September 15-18 at Spectrum, Collide-O-Scope Music begins its eighth season with a Festival celebrating the music of Robert Morris. A wide range of works will be featured, for electronics, piano, small chamber ensemble, and string quartet. In addition to Collide-O-Scope personnel, there will be guest performers, notably JACK Quartet. I recently interviewed Morris about the upcoming concerts: our exchange follows.

How did this Festival of your music come about?

Out of the blue, on April 20, 2015, I received an email from Augustus Arnone proposing this festival of my music. I had never met Augustus nor heard him play in person, but I knew of his great pianistic talent and industry in playing the complete works of Milton Babbitt and the complete “History Of Photography In Sound,” by Michael Finnissy. I knew also of his new music ensemble called Collide-O-Scope. He proposed that the festival should feature my piano works (of which there are many), my small ensemble pieces, some of my electronic works, and string quartets, which would be played by the JACK Quartet. The members of the JACK were once students at Eastman where I teach, and two of them had studied composition with me. They have premiered two of my string quartets: Arc (1988) and Allegro Appassionata (2009) written for them. They will also play my most recent quartet called Quattro per Quattro (2011).

Why was Spectrum picked as the venue?

Spectrum is a New York City performance space that is well known for presenting progressive art and music. Collide-O-Scope has played there many times. In the last five years, more intimate informal performances spaces, by contrast with concert halls, are becoming the norm for new music concerts and events. This is perhaps a tradition that stems from the old NYC downtown music venues of the 1980s and 90s for alternative and improvised music.

What will the pieces for electronics be like? How do you think they will resonate in an intimate environment like Spectrum?

The electronic/computer music pieces are not that loud as such things go. One of the two pieces called Mysterious Landscape is quite intimate in character, while the other piece, Entelechy 2012 for piano and electronic modification, is sometimes brash and dramatic with subtle, timbreally unique gestures often including microtones, vibrati and glissandi—categories of sound impossible to produce on acoustic keyboard instruments.

These two pieces, both composed in 2012, complement each other in other ways. Mysterious Landscape is an improvisational electro-acoustic piece lasting about 30 minutes to be played by one or two performers. It complements my desire to connect music with nature as in my outdoor pieces. Here the sounds and processes of nature are brought inside a performance space so that natural sounds—birds, insects, frogs, mammals, wind, and water-—are mixed together with computer-generated sounds to project a serene sonic environment that reflects on a peaceful relation of humans to nature. I will play the piece with a video slideshow using landscape photographs I took in the southwest and eastern United States, south India, Sri Lanka, and Kyoto, Japan.

Entelechy 2012 is quite a bit more abstract in structure and design. It also involves indeterminacy, but of the composed type; in this case, two isomorphic, composed out structures are played against each other in a different coordination from one performance to another. This underlying structure is based on a ring of 24 elements that include all the permutations of four elements once each. This ring guides the timbres, gestures, and pacing of the piece. However it does not produce a sense of stability or unity in any of the performances. Rather the composition is designed to be radically impermanent, providing surprising and novel experiences as it moves on, as much as in jerks or surges as ebbs and flows. Incidentally, The word “entelechy” was coined by Aristotle to refer to the condition of a thing whose essence is fully realized, implying an actuality that directly stems from some potential idea or concept. Augustus will play the piece with sound modifications that are not controlled by a live performer.

Both pieces use MAX-MSP patches

More on these pieces can be found on my website:

http://lulu.esm.rochester.edu/rdm/notes/ml.html

http://lulu.esm.rochester.edu/rdm/notes/ent12.html.

Do you enjoy being part of the performances of your electronics installations?

Yes, I do. I enjoy improvisation, on one hand, and being in control of the nuance of the electronic sounds, on the other.

You’ve frequently composed for piano. What draws you to the medium?

I began playing piano before I could read music and took lessons. Even today, I improvise as much as I play written-out compositions; however in recent years, I play for myself only. Thus the piano has been the instrument on and from which I get musical ideas of all sorts, and is often the medium in which I try out new compositional ideas and modes of expression. I like to contrast the percussive and dynamically mobile character of the piano—which you find most prevalently in jazz of all types–with the colorful and intimate resonances found a good deal of new music. You might say, Bartok, Stravinsky and Babbitt versus Debussy, Boulez, and Feldman.

The piano program contains the premiere of a new work, Foray (2016). What were some of the compositional ideas you worked with in this latest piece?

Foray was directly influenced by Augustus’s playing, which I finally heard live last spring in a Collide-O-Scope concert featuring the music of Milton Babbitt and some younger composers. His remarkable ways of voicing and articulating piano sound made a big impression on me. So in mid-July an idea for a piano piece popped into my head and the character of the piano ideas was something I thought Augustus would like to play, so I dedicated the piece to him. The basic idea of the piece is that an opening series of ten chords arranged in an arc (maybe a rainbow, since each chord is of a different harmonic “color”) each generate music in subsequent sections of the piece. Thus the form is the arc followed by ten sections in different registers and densities. As the music goes on, the derivation of the music from the chords gets progressively more complicated and obscure in the way the music is parsed, registered, and embellished. The process is from isolated objects to mixtures and blends—an entropic process.

By the way, the other pianist on the program, Margaret Kampmeier, is also playing music I dedicated to her: from my Nine Piano Pieces.

Have your works been performed before by Collide-O-Scope Music? What does their ensemble bring out in your work that perhaps others don’t?

Well, not exactly. Some of the players who are members of Collide-O-Scope as well as guest artists on this festival have played and recorded my music. Sunghai Anna Lin (violin), Margaret Kampmieier (piano), Marianne Gythfeldt (clarinet) and Tara O’Connor (flute) were once members of the New Millennium Ensemble that played and recorded my sextet Broken Consort in Three Parts, as well as other pieces over the years. These are wonderful musicians who understand how to interpret the multiplicity of structure and expression in my music.

Could you tell us a bit about the ensemble works that will be heard on the festival?

Traces (1990) for flute and piano was commissioned by the National Flute Association in 1990 as a contest piece. As the title suggests, the piece moves forward by tracing and retracing various melodic lines in the piano by the flute and vice-versa,

Raudra for flute alone was written for Elizabeth Singleton in 1976. It takes its name from the fourth of the nine “rasa’s” of Indian music and dance, connoting the mood of fury and anger. I’m looking forward to Patricia Spencer’s performance.

Along A Rocky Path (1993) was composed for the Arlington Trio (violin, clarinet and piano). Like many of my pieces, Along a Rocky Path reflects aspects of natural landscape—especially less frequented and more rugged terrain. Shortly after completing the piece in January 1993, I came across a poem of the eighteenth-century Japanese poet, Uragami Gyokudo, from which I took the title of my trio.

There is no heat on this rocky path,

The sound of the water from a mountain stream is most pure,

By the red leaves, I know there must be a man’s hut nearby;

My traveler’s path is hidden in the white clouds.

Over the twisting path hang the waterfalls of Mount Lu,

The plank roads of Szechwan cross the steep mountains.

There is no need to bemoan the journey:

Wherever I chant my poems is home.

Out and Out (1989) was composed for Marianne Gythfeldt in the spring of 1989. It concerns the interplay between the two instruments; the clarinetist and pianist interact to shape the musical continuity, often doubling each other’s notes and rhythms. The resulting demarcation of one musical line by another affects every aspect of the piece, producing exceedingly great reaches of reference, pulling together music from every part of the piece.

Drawn Onward (2014) is a recent work for violin and piano written for the Irrera Brothers, an emerging violin/piano duet. The title of the piece involves a palindrome that is embedded in the following longer palindrome: “Are we not drawn onward, we few, drawn onward to new era?” The idea of a symmetry inside another symmetry is at the heart of the composition. For instance, each of the two players has their own musical materials, but the violin material is embedded in the piano material and vice versa. Since the two performers from whom I wrote the piece are brothers, I thought that working with mutually embedded materials an apt way of composing a piece particularly for them.

Did the JACK Quartet work with you when they were at Eastman?

As I mentioned earlier they did as composition students, but they were not the JACK Quartet yet. You can read about the interactions we have had in the following interview article: “Interview with the JACK Quartet, John Pickford Richards, Ari Streisfeld, Christopher Otto, Kevin McFarland, And Joshua B. Mailman,” Perspectives of New Music, (2014) 52/2.

String quartets often are particularly significant pieces in composers’ respective outputs. How would you characterize the quartets that will be heard on the festival?

Although I wrote a string quartet in 1976, Arc of 1988 is my official first quartet. Due to the difficulty of the music, I had to wait 21 years before it was played. The JACK decided to learn it in 2008 and have played it here and there since then. The second quartet, Allegro Appassionata, was written for the JACK in 2009 for a special concert at the Tank in NYC. The third, Quattro per Quattro was premiered and recorded by the Momenta String Quartet in 2014 with Benjamin Boretz’s string quartet, Qixingshan. Now I will hear the JACK’s interpretation!

Are these quartets significant in my output? I think yes: they are all extended, ramified compositions; each embodies a harmonious relation between singular compositional craft and intense emotional particularity; each is quite challenging for the performers. But as your question implies, string quartets are considered the high-water mark for composers of all stripes. I can only hope my quartets will be appreciated as such.

______________

Sep 15 – 8:00 pm

Robert Morris Festival, Concert I – Electronic Installation Works

Augustus Arnone, piano, and Robert Morris, Electronics

Mysterious Landscape (2012)

Entellechy (2012)

(pre-concert discussion with Morris at 7pm)

Sep 16 – 8:00 pm

Robert Morris Festival, Concert II – Music For Solo Piano

Augustus Arnone and Margaret Kampmeier, pianos

39 Webern Variations (2010)

Sabi (1998)

Night Vapors (1967)

Wabi (1996)

Lake (2016)

14 Little Piano Pieces (2002)

Foray (2016) ** World Premiere

(pre-concert discussion with Morris at 7pm)

Sep 17 – 8:30 pm

Robert Morris Festival, Concert III – Music For Mixed Ensemble

Collide-O-Scope Music

Traces (1990)

Raudra (1976)

Along A Rocky Path (1993)

Out and Out (1989)

Drawn Onward (2014)

Yugen (1998)

Sep 18 – 3:00 pm

Robert Morris Festival, Concert IV – Music For String Quartet

JACK Quartet

Arc (1988)

Allegro Appassionata (2009)

Quattro per Quattro (2011)

________________________________________________________

Spectrum

121 Ludlow St. 2nd fl, New York City

September 15th – 18th

TICKETS: 20$/15$ (students and seniors) OR Festival Pass 50$/40$ (students and seniors)

________________________________________________________

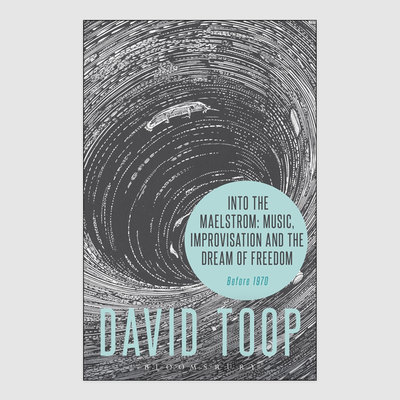

Into the Maelstrom: Music, Improvisation, and the Dream of Freedom before 1970

By David Toop

Bloomsbury, 330 pp.

Even given the relative expanse of a projected two-volume history of improvised music, David Toop has set lofty goals for himself. In volume one, Into the Maelstrom: Music, Improvisation, and the Dream of Freedom before 1970, he discusses a number of musical figures from improvising communities: Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Steve Beresford, Keith Rowe, Ornette Coleman, and Eric Dolphy are a small sampling of those who loom large. John Cage is a totemic figure discussed from a variety of angles. Such collectives as AMM, MEV, Spontaneous Music Ensemble, Company, and Gruppo di Improvvisazione Nuova Consonanza feature prominently as well. In addition, Toop connects improvisation to a panoply of other reference points, musical and otherwise, such as rock, concert music, fine art, film, and literature. Politics and historical events and their influence on musicians is a particularly well-drawn through line.

One would be hard pressed to take a strictly chronological approach to reading Into the Maelstrom. A great pleasure is the oftimes improvisatory feel of its labyrinthine passages. In this sense it jubilantly resembles the Edgar Allen Poe story from which it takes its title. No matter how far-flung a new passage may at first seem, Toop finds a way to integrate it into the fabric of the book. For the most part, Maelstrom is confined to the genesis and development of free playing in the decades leading up to 1970. Digressions from this era, such as transcribed later interviews and personal anecdotes, are used to provide a more comprehensive portrait of particular figures and incidents. Nor does Toop eschew discussion of earlier figures. Indeed, his profiles of musicians such as Art Tatum, Erroll Garner, and Stuff Smith trace a lineage of free playing, or at the very least playing on the cusp of free, that is farther reaching than is often enough acknowledged. Flashbacks and flashforwards are also employed to tease out thematic issues, such as audience responsiveness (or non-responsiveness, and occasionally dangerous hostility), interaction between musicians (with its own degrees of responsiveness and even dangerous hostility), and, especially, issues of freedom, both in musical and political contexts. Thus, Into the Maelstrom allows us a glimpse into an ever-changing landscape of varying interactions, all of which contribute to the development of improvisation. I’m eager to read its companion second volume.

Congratulations to composer and multi-instrumentalist Henry Threadgill, who has won the 2016 Pulitzer Prize in music. One of the original AACM members, Threadgill’s recent work has been distinguished by an intervallic approach to improvisation, in which each member of the band has a limited catalogue of intervals that they can perform, with the sum total creating intriguing harmonic and contrapuntal materials.

In for a Penny, in for a Pound, the prizewinning work, features Zooid, the band with which Threadgill has worked for fourteen years, using just such an approach to making music. In addition to two short movements, Threadgill has composed long movements that each successively feature a different member of Zooid.

Threadgill’s latest recording, Old Locks and Irregular Verbs, features Ensemble Double Up, the first new band with which he has recorded in fifteen years. It includes pianists Jason Moran and David Virelles, alto saxophonists Roman Filiu and Curtis MacDonald, cellist Christopher Hoffman, tuba player Jose Davila, and drummer Craig Weinrib. Cast in four movements, it is dedicated to the late Butch Morris, channeling some of his “conduction” style of improvisation.

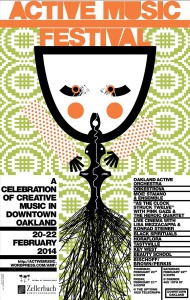

The San Francisco Bay Area has long been a friendly and nurturing environment for musicians “without a home” – operating between and outside of genres. For those shut out of the concert halls and jazz clubs, it’s been a haven where non-traditional musicians build non-traditional alliances, and run non-traditional music venues and concert series where they can take risks and create uncompromising work. Over decades of community-building and creative ferment, this lack of formal boundaries has defined the sound and feel of the scene, interweaving free improvisation with elements of noise, minimalism, rock, jazz, drone, chamber music, electronica, and other more slippery sounds which resist categorization.

The San Francisco Bay Area has long been a friendly and nurturing environment for musicians “without a home” – operating between and outside of genres. For those shut out of the concert halls and jazz clubs, it’s been a haven where non-traditional musicians build non-traditional alliances, and run non-traditional music venues and concert series where they can take risks and create uncompromising work. Over decades of community-building and creative ferment, this lack of formal boundaries has defined the sound and feel of the scene, interweaving free improvisation with elements of noise, minimalism, rock, jazz, drone, chamber music, electronica, and other more slippery sounds which resist categorization.

The scene’s relentless DIY approach has led to the establishment of numerous artist-run concert series and festivals, of which the Outsound New Music Summit, the Tom’s Place house concert series in Berkeley, the SIMM Series at the Musicians’ Union Hall, the Wednesday and Sunday series at the Berkeley Arts Festival Space, and the San Francisco Electronic Music Festival are just a few examples. This month they’ll be joined by a brand-new one, the Active Music Festival, covering February 20-22 in downtown Oakland. (more…)

Ted Byrnes, Nicholas Deyoe and John Wiese joined forces on Tuesday, December 17, 2013 for an evening of improvisational music featuring percussion with guitar and electronics in a concert titled 2 Duos of Varying Volumes But Similar Intensities. About 25 people, a near-capacity crowd for the renovated loft space that is the Wulf, heard three different offerings in two duo configurations that included a wide variety of extended techniques.

Ted Byrnes, Nicholas Deyoe and John Wiese joined forces on Tuesday, December 17, 2013 for an evening of improvisational music featuring percussion with guitar and electronics in a concert titled 2 Duos of Varying Volumes But Similar Intensities. About 25 people, a near-capacity crowd for the renovated loft space that is the Wulf, heard three different offerings in two duo configurations that included a wide variety of extended techniques.

Ted Byrnes is a drummer/percussionist living in Los Angeles via the Berklee College of Music in Boston and who is working now primarily in free improvisation, electro-acoustic music and noise. Nicholas Deyoe is a composer and has also conducted the La Jolla Symphony as well as Red Fish Blue Fish. John Wiese is a Los Angeles-based freelance musician who’s collaborated with visual artists, installed noise works in nontraditional spaces, and once helped curate a split-series tied to online casinos in UAE experimenting with experimental music licensing models. He has toured extensively in Europe and Australia.

The first piece – Duo 2 – had Ted Byrnes stationed behind a more-or-less familiar drum kit, but with a number of unusual found objects within arm’s reach. Nicholas Deyoe accompanied on an acoustical guitar and began the piece with a loud shout. This was followed quickly by the application of palm fronds on the tom-tom and this produced a soft, pleasantly organic sound. Guitar chords joined in as well as a variety of slaps, plinks and more exotic sounds that were conjured by an animated Nicholas Deyoe.

As the piece progressed Ted worked through a series of objects directly on the drum head – pot lids, sheet metal plates, a hollow metal cymbal stand – these were struck with drum sticks, brushes, and even the performer’s knuckles. A cymbal was removed and placed on the snare drum head and played with brushes, producing a wonderfully complex sound. Dice were heard knocking within cupped hands. Even with all the movement that was required to sustain the sound, you could see the precision with which each object was obtained, incorporated in the percussive mix and then returned, with the flow of energy never lessening. The result of all this was a sort of rolling sea that came in waves of varying dynamics and intensity. Less a rhythm than a wash of percussive sounds, some familiar and some almost industrial in character, but all suffused with great energy even in the quieter moments.

The second piece – Duo 1 – combined Ted Byrnes with John Wiese on electronics. John was equipped with a sound board that allowed him to mix about a dozen different sounds that originated from a laptop computer. An amplifier and a series of speakers completed this set up. The electronic sounds added a solid foundation against which the sharp sounds of the percussion could offer some interesting contrast. Long booming sounds, screeches and squeals provided a continuous electronic texture while the ever-energetic Ted provided a varied mix of rapid percussion. To my ear the drumming seemed just a bit more conventional and offered a point of reference to the sometimes alien sounds coming from the speakers. But overall the balance with the electronics seemed just right and very effective. At times this piece was full of roar and commotion, but never seemed stressed or distorted. Duo 1 concluded nicely with disarmingly warm tones from the electronics that faded to silence.

The third piece of the evening had Nicholas Deyoe on guitar rejoining Ted Byrnes in a final duo. There were some amazingly high sounds produced from a single guitar string combined with the usual activity in the percussion that at times seemed an virtual avalanche of sound. The drumming again sounded a bit more traditional and the dynamics in this piece were more noticeable. Although similar in texture to the first piece, this last duo surged in and out a bit more regularly – like watching the whitecaps on a choppy sea.

The percussion techniques used in this performance are interesting because all the extra found objects could have just as easily been hung separately to be struck individually, but Ted Byrnes has chosen to make them integral to the drum kit and applied them together. This produces many unusual sounds to be sure, but also mixes the familiar and the unfamiliar in a more calculated and artistic way. These pieces pushed the limits of rhythm, texture and density in new directions and invite the listener to rethink previously implicit musical boundaries.

The Wulf will present another concert of duo improvisational music on January 29, 2014 at 8:00 PM that will feature Bonnie Jones and Andrea Neumann, whose work ” is a rich contradiction of textures and timbres with each artist committed to both defining and expanding the definitions of their music through long-term collaboration.”

The Wulf will present another concert of duo improvisational music on January 29, 2014 at 8:00 PM that will feature Bonnie Jones and Andrea Neumann, whose work ” is a rich contradiction of textures and timbres with each artist committed to both defining and expanding the definitions of their music through long-term collaboration.”

Imani Winds: Jeff Scott, Toyin Spellman-Diaz, Valerie Coleman, Monica Ellis, and Mariam Adam. (Photo by Matthew Murphy)

(Houston, TX) Since the group’s inception in 1997, the Imani Winds have continued to expand the relatively small-sized repertoire for wind quintet by commissioning several works by such forward-thinking composers as Alvin Singleton, Roberto Sierra, Stefon Harris, Daniel Perez, Mohammed Fairouz, and Houston’s own Jason Moran. Moran’s four-movement work Cane, Moran’s first composition for wind quintet, appears on the Imani Winds’ 2010 album Terra Incognita, along with pieces by two other jazz masters, Paquito D’Rivera and Wayne Shorter. (The Imani Winds appear on Shorter’s critically acclaimed 2013 live quartet album Without A Net in a scorching performance of his 23-minute through-composed work Pegasus.) Imani Winds members Valerie Coleman (flute) and Jeff Scott (horn) also compose and arrange for the quintet. In concert, the Imani Winds present traditional classical fare alongside new works that explore African, Latin American, and the Middle Eastern musical idioms and performance techniques.

On Tuesday, October 15, 2013, the Imani Winds make their Houston Friends Of Chamber Music debut at Rice University’s Shepherd School of Music, performing arrangements of classic works by Ravel and Mendelssohn, Jonathan Russell’s powerful wind quintet arrangement of Stravinsky’s The Rite Of Spring, and Scott’s arrangement of Palestinian-American oud and violin virtuoso Simon Shaheen’s composition Dance Mediterranea, a piece that requires the quintet to play and improvise with Arabic scales or maqamat.

I spoke with Jeff Scott about the challenges of arranging Shaheen’s piece for the quintet as well as what it means to be a chamber wind ensemble in the 21st century.

Chris Becker: What are some challenges you faced in arranging Simon Shaheen’s music for the Imani Winds?

Jeff Scott: I listened to Shaheen’s piece over and over and over again so I could learn what I could do in the different section to offset it. We are an ensemble with five completely different sounding instruments that can create many different colors. So I listened to each section and thought, “Who could play the bass here? Who would sound great playing the solo line here? Who could really do something percussive on their instrument there to make it sound like an authentic version of the song?”

CB: There’s improvisation in your arrangement? Is that correct?

JS: Absolutely.

CB: Can you talk a little bit about the improvisation in the piece? Are you and your fellow winds improvising with scales? Are you improvising over some kind of harmony? Or is it even freer than that?

JS: It’s definitely structured. In that part of the world, the scale is called a maqam. This piece deals with three different maqamat. So for the solo sections, I only wrote out a rhythmic figure for whoever is playing the bass and the scale itself for whoever is playing the solo. The stuff in the middle is fleshed out completely and gives the top and bottom players guidelines they can follow.

In preparation for this piece, we had workshop rehearsals for learning the different maqamat and how to play inflect on our respective instruments the quarter tones and semitones that exist in those scales, so we wouldn’t just be playing a diatonic scale with two half steps and then calling that a maqam. That’s not it at all. The challenge was getting that g half flat just so! (laughs)

What separates people who play with those different scales and people who play Western music and diatonic scales, is that our ears are adjusted. We know when someone is playing a flat seventh, you know? But to be able to play it as part of a scale and know whether or not you’re just flat enough? (laughs) That’s a different thing! We played these scales in workshops for Shaheen almost like we were auditioning for him. We’d play, and he would say, “No, no, no…” and then play the scale with us and show us exactly where they fit. It’s a thing you just constantly have to work on because it’s not a part of our pedagogue. It’s not part of our training.

Before playing this piece, we’ll have our set of rehearsals the week before, and we’ll go through the shed of practicing those scales and testing one another.

CB: Is improvisation a part of your background? Or is it something new that you and the other members of the Imani Winds have explored since coming together as an ensemble?

JS: I’d say for the most part it’s new. Improvising wasn’t a part of our formal training. We all went to either the Manhattan School of Music or Juilliard. And it just wasn’t asked of you, it just wasn’t. Now, post-school? Yeah. You realize that in the 21st century commercial world, if you’re going to survive, regardless of what your training is, you have to be flexible enough to improvise. It was definitely harder for us coming into it, but more schools are requiring it these days. I think that’s really wonderful. The language of music from other countries is now filtering its way into the Western chronicles and as a musician, you have to be able to speak the different dialects. We have embraced it and really went out there and grabbed every possible challenge we could.

CB: What you say about conservatories in the U.S., that more programs are including improvisation and music from around the globe, is something I’m hearing about more and more in my interviews with younger musicians.

JS: It used to be shunned. When I was at the Manhattan School of Music, back in the 80s, I wrote this piece for horn and percussion that I wanted to play on one of my recitals. I remember playing the piece for my teacher and him not wanting me to do it because most of my part wasn’t written down and he couldn’t work with me on it. It wasn’t because the it sounded “bad” or “good,” he just didn’t know how to work with me on it as an improvised piece of music. And that said a whole lot about the institution and my training in general! (laughs) It speaks volumes!

CB: Tell me about the Imani Winds’ collaboration with saxophonist and composer Wayne Shorter.

JS: We were asked to come and perform with him at the Hollywood Bowl on his 80th birthday along with Esperanza Spaulding, Herbie Hancock, Dave Douglas and all of these incredible musicians. We performed a piece that Shorter composed and arranged called Pegasus. It’s a symphony! The piece is written for his and wind quintet. It’s a symphony! It’s a mammoth, epic journey with improvisation from everyone involved, a through-composed piece with many different moods.

The whole thing started when the La Jolla Music Society in California commissioned Shorter to compose a piece for us, which he titled Terra Incognita. It was just for wind quintet, and it was the first piece he’d composed that didn’t involve him as a performer. He’d never written something for someone else that he didn’t intend to perform.

So he wrote this wind quintet and it was way out (laughs) with just as much room to improvise as you could possibly want. We didn’t know what the heck to do with it. So we learned everything note by note, and then played it for him. And he smiled and said, “That’s great. But promise me you’ll never play it like that again. I want you play it different every time. I want you to start from the end. I want you to leave out some parts. You can start in the middle. Just use the piece as a point of departure.”

CB: That’s so great.

JS: It says a whole lot about him. But it also says a whole lot about where I think classical music in general is going when it comes to chamber music and accepting improvisation, jazz and all of the world’s music, and having musicians who are flexible enough and open enough to at least experiment. It’s the only way we’re going to get the patrons of chamber music societies to have that openness and expectation when it comes to who they decide to put on their series. I mean, if we don’t start doing it, they’re going to continually only want the Haydn cycles. (laughs)

So we have to not only accept it, we have to become nimble at it. You have to be able to deliver a good product so the patrons say, “You know what? I want more of that!”

And besides, as a wind quintet, we don’t have the Haydn cycles! (laughs) They just don’t exist. We occasionally play the old stalwarts of the wind quintet, but that stuff runs out in about two weeks. You’ve got to play new stuff and push the envelope a bit, and improvisation is just a normal step along the way for expanding the repertoire for the wind quintet.

Houston Friends of Chamber Music present the Imani Winds, Tuesday, October 15, 7:30 p.m. at Stude Concert Hall, Shepherd School of Music, Rice University, performing works by Valerie Coleman, Mendelssohn, Ravel, Simon Shaheen, and Stravinsky’s The Rite Of Spring arranged by Jonathan Russell.

(Houston, TX) If Houston is becoming, as one young Houston-based composer puts it, a “hub for contemporary music,” credit must be given to more than a few local ensembles, organizations, and venues that operate without institutional support and on shoestring budgets. Contemporary music ensembles made up of university professors and their students performing contemporary music in universities for other professors and students are nothing new. But composers who not only write, perform, and creatively program contemporary music and present it outside of academia in venues typically dedicated to performance art, experimental rock and underground noise? That’s a little more interesting, and certainly more conducive to expanding audiences for 21st century composition.

Houston-based composer Paul Connolly understands this. As the curator and producer of Brave New Waves, which was born out of electronic and video artist Jonathan Jindra’s Binarium Sound Series and is currently Houston’s only concert series dedicated solely to electronic music, Connolly has worked hard to bring seemingly disparate artists and audiences together to share and experience new sounds. On October 2,3, and 5, as part of the sixth annual Houston Fringe Festival, Connolly shifts roles from producer to composer to premier The Quiet Persistence Of Memory, an original electro-acoustic composition that, not surprisingly, will be performed by a wildly diverse collection of Houston musicians and improvisers.

The Quiet Persistence Of Memory is scored for bass, tenor, and soprano voices, viola, harp, contrabass, percussion, and analog modular sound tools. The ensemble Connolly has gathered to perform this work includes Aaron Bielish (viola), Kathy Fay (harp), Thomas Helton (double bass), Luke Hubley (percussion), John Pitale (percussion), Ben Lind (narration), Misha Penton (soprano), Matthew Robinson (tenor), and SPIKE the percussionist (percussion, electronics). Each of the three scheduled performances of The Quiet Persistence Of Memory will feature a slightly different configuration of the performers. The score, which Connolly describes as “a time-based grid that allows the performers to both see their part as well as existing parts of others that have been prerecorded,” is augmented by live improvisation and accompanying visuals.

“When I first began conceptualizing the piece,” says Connolly, “it probably had an equal balance between acoustic instruments and electronic material. However, the piece has evolved to where it has become very much a totally acoustic instrument work, with live electronics that are used almost like Foley in film. Very subtle, and simply providing a background that’s not necessarily noticeable.”

The title of the piece, aside from its nod to the surrealist painter Salvador Dali, refers to “the process by which information (i.e. memory) is encoded, stored and retrieved.” Connolly’s compositional process, which included recording studio performances by many of the participating musicians and incorporating those recordings into the piece for the same musicians to “remember” and react to in the live performances, speaks to the subject of how memory is utilized, disrupted, and (de)valued “in a hyper-information rich society.”

No two of the three performances of the piece will be alike, and kudos must go to the folks behind the Houston Fringe Festival for scheduling multiple opportunities for audiences to hear and experience Connolly’s music.

Paul Connolly presents The Quiet Persistence Of Memory October 2, 5, 9:30 PM and October 3, 8:00 PM at Super Happy Fun Land, 3801 Polk Street, Houston, TX. Part of the sixth annual Houston Fringe Festival.