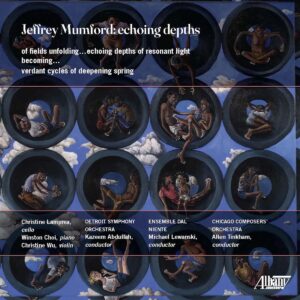

Jeffrey Mumford

Echoing Depths

Albany Records

Jeffrey Mumford’s music channels high modernism into imaginative works that are luminously textured. His latest Albany release, Echoing Depths, features two pieces for orchestra and another for piano and ensemble. All three are concertos, a form that befits Mumford’s penchant for virtuosity.

The cello concerto Of fields unfolding … echoing depths of resonant light is dedicated to the composer Elliott Carter, a centenarian who passed away in 2011. Carter has been a key influence on Mumford’s music and was one of his composition teachers. Christine Lamprea is the soloist with the Detroit Symphony, conducted by Kazem Abdullah. Lamprea is a skilful cellist, and her intonation is clear, even in angular motives and widely stretched multi-stops. Her performance of the piece, energetic and crystalline, is reminiscent of Fred Sherry’s rendition of Carter’s Cello Concerto. Indeed, the piece itself channels Carter’s concerto style, with disparate scorings depicting various demeanors in a complex colloquy. Of Fields unfolding…’s several cadenzas are abundantly virtuosic, and Lamprea assays them with command. Detroit has become an imposing ensemble in recent years, and they address the considerable demands of the score with aplomb, Abdullah leading them in a rousing performance.

Becoming is a chamber concerto for piano. Winston Choi is the soloist with Ensemble dal Niente, conducted by Michael Lewanski. The overlapping of pitched percussion and piano creates a super instrument redolent of fleet and punctilious articulations. Choi has made a specialty of Elliott Carter’s music, and thus has an entryway to Mumford’s style that relatively few other artists have. His tone is brilliant and incisive, which better matches the correspondence with the percussionists. Ensemble dal Niente is a go-to group for contemporary music, and Lewanski is the conducting equivalent. Becoming is elegantly shaped and a microcosm of Mumford’s music writ large.

Mumford’s second violin concerto, Verdant cycles of deepening Spring, is the final work on the disc. Soloist Christine Wu joins the Chicago Composers Orchestra, conducted by Allen Tinkham. The ensemble is well-rehearsed, with corruscating entrances and complexly balanced timbres rendered with authority. Tinkham excels at dealing with the frequent tempo shifts and, once again, it is impressive how accurate the recording is. Wu is an imposing soloist, playing the mercurial passagework, wide leaps, and frequent dynamic contrasts with attitude and accuracy. She has a supple, versatile tone and embodies the sense of conflict that typifies the piece.

Echoing Depths has the high quality of performances that most composers dream of when putting together a portrait CD. Mumford’s chamber works were previously familiar to me, but this disc of concertos shows that his music is a powerful force when writ large. Recommended.

-Christian Carey