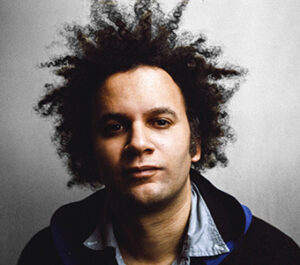

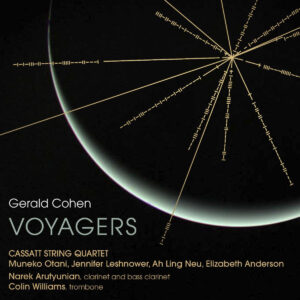

Gerald Cohen

Voyagers

Innova Records

One can think of few chamber ensembles better suited to contemporary music than the Cassatt String Quartet. Their intonation, musicality, and interpretive powers are superlative. Composer Gerald Cohen has enlisted them to record three of his pieces on Innova, two originally commissioned for Cassatt.

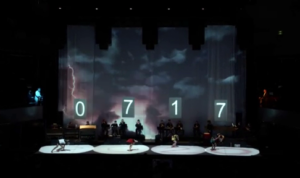

Cohen describes himself as a storyteller, both in his vocal and instrumental music. The three distinct narratives here are populated by musical quotations relevant to them, yet they never seem like pastiche. The title work is about the two Voyager spacecrafts, which were sent out into our solar system with a golden record of musical examples. The hope was that they could be played by any extraterrestrials that might be encountered, and give a sense of the cultural life on planet Earth.

The piece is for clarinet – played by Narek Arutyunian – and quartet. Four attacca movements each transform the material from a different selection on the gold record. “Cavatina” deals with the analogous section from Beethoven’s String Quartet Op. 130. Cohen also imagines it as the beginning of the spacecrafts’ journey. Shadowy harmonies and a limpid high violin line start the movement, which over the course of nine-and-a-half minutes treats Beethoven’s music in a highly individual way.

The second movement, “Bhairavi,” deals with a raga. Arutyunian embodies the complex scalar patterns of the music with nuanced shaping, as do the members of the quartet. The accompaniment is deliberately simple – pizzicato repeated notes. As the movement develops, there is hocketing of the tune between the various players. “Galliard” is the quartet’s Scherzo movement, based on “The Fairy Round” by renaissance composer Anthony Holborne. Scraps of the tune are exchanged contrapuntally in a humorous, whirling dance. “Beyond the Heliosphere” concludes the quartet with sustained pitches in a complex of intricate harmony, a descending melody, sometimes winnowed down to just a minor third interval, passing from part to part. The Cavatina theme, followed by a high note from bass clarinet, send the Voyagers continuing on their journey.

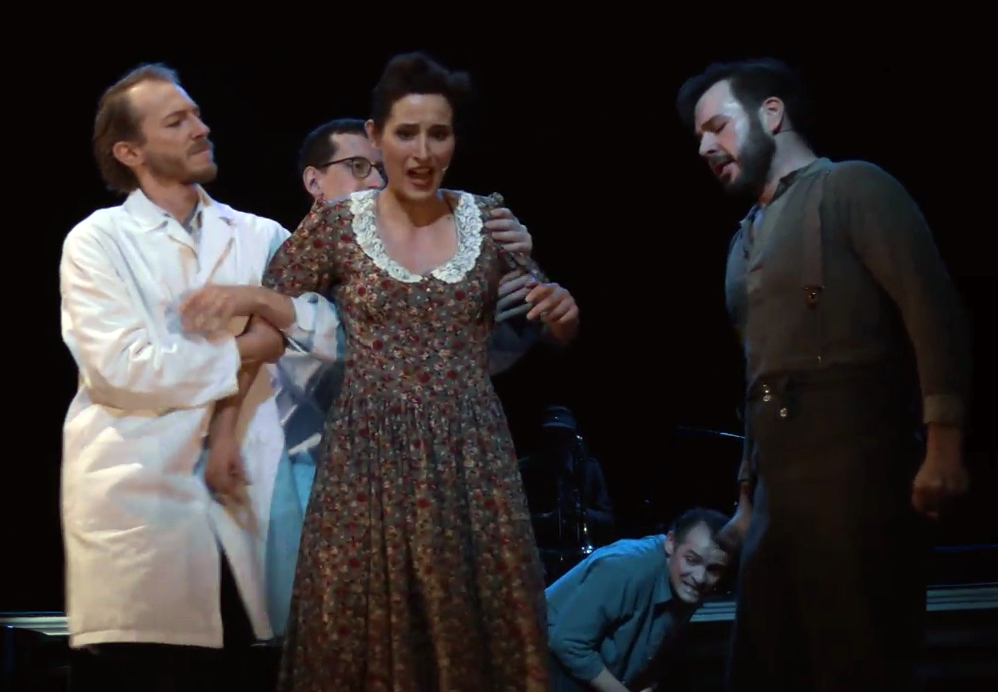

Playing for Our Lives is a piece for quartet about the Terezin concentration camp, a “show camp” where the Red Cross was allowed admittance to see better conditions than the hellish death camps where prisoners would later be deported. Music-making was encouraged, and many pieces created in Terezin have survived, demonstrating the talent and resiliency of their creators. By far the most famous is Viktor Ullmann, whose opera Der Kaiser von Atlantis has entered the repertory. While in the camp, Ullmann arranged Beryozkele (“Little Birch Tree”), a popular Yiddish song. Cohen uses the song’s melody as a touchstone in the first movement. Other songs that are quoted are Czech, Hebrew, and Yiddish songs. The second movement “Brundibar,” takes as its title that of the children’s opera composed by Hans Krása.” The title of the entire work, Playing for our Lives, is based on a quote by one of the few survivors of the orchestra that played at Brundibar’s premiere, Paul Rabinowitsch, a then 14-year old trumpeter. The adolescent feared playing wrong notes, lest he be deported by the SS for his mistakes.

At first I found the last movement’s inclusion of the Dies Irae from Verdi’s Requiem to be curious, but recognized after a few listens that is a response to the SS officers who ran the camp, that they would be called to account for their evil deeds. Cohen’s music embodies the twentieth century neoclassicism and folk influences of the composers at Terezin, all the while presenting an eloquent rejoinder to hate and anti-Semitism. Thus, it is a timely work.

The recording closes with an unusual ensemble grouping: the Cassatt Quartet is joined by trombonist Colin Williams in a heterogenous quintet, “Preludes and Debka.” Once again, the connection to the present is palpable. A debka is a Middle Eastern circle dance, performed both by Jewish and Arab people at social gatherings, such as weddings. Sometimes the trombone is used for bass pedals, but more often it plays melodies as doublings or in counterpoint. Cohen manages to balance things well so that the trombone doesn’t overwhelm the strings, and Williams plays his solo turns, including a mid-piece cadenza, with supple lyricism. After the cadenza is a long, moody duet between first violin and trombone, a break in the dance rhythms. Gradually, the dance rhythms reinsert themselves into the texture, with an accelerando back into the debka. Apart from a few interjections of the slow central music, it whirls until the piece’s coda, where there is another lyrical interruption, and the dance comes to a jaunty conclusion.

I couldn’t help imagining people from throughout the Middle East’s various faiths coming together and dancing. It seems far away at this writing, but Cohen’s eloquent piece stirred this hope in me. Cohen is a gifted storyteller and an equally formidable composer. The Cassatt Quartet once again prove to be stalwart advocates for contemporary music. Voyagers is one of my favorite releases of 2023.

-Christian Carey