Irving Fine was a Boston boy through and through. Born on December 3, 1914, in East Boston to Latvian Jewish immigrants, he grew up in Winthrop and went to Harvard. The Boston in which Fine grew up was, through the influence of the Boston Symphony and its conductors Pierre Monteux and Serge Koussevitzy and the Harvard Music Department and its composition professors Edward Burlingame Hill and Walter Piston, among other factors, a world center of new music (or at least francophile new music) activity, and the work of Harvard’s choral conductor Archibald T. Davison at Harvard also made it the center and exemplar of serious music education and choral training in the United States. Possibly the high water mark of this importance was when, during the time Fine was a graduate students at Harvard, Igor Stravinsky came to Boston as Harvard’s Charles Elliot Norton Professor of Poetics; Fine was designated as a minder for Stravinsky, and was also assigned to help with the initial translation of his lectures, which became The Poetics of Music. In 1940 Fine joined the faculty of the Harvard Music Department as a teaching fellow; in 1942 he was appointed an instructor, a position he held until 1948.

From the beginning Fine’s association with Harvard was intertwined with Anti-Semitism. He was one of two students at Winthrop High School to apply to Harvard; the grades of the other student, who was not Jewish, were less good, but he and not Fine was accepted. (All of the Ivy-League colleges had quotas of the percentage of Jews they would admit.) After a “post-graduate” fifth year of high school at the Boston Latin School, where he met Leonard Bernstein, who became a life-long friend, Fine applied again to Harvard and was admitted. When as the vice-president of the Harvard Glee Club, Fine applied for membership to the Boston Harvard Club, which, although not directed affiliated with the university, had a policy that all officers of Harvard clubs were entitled to membership, he was informed that “his kind” were not accepted. Later, when he was on the faculty at Harvard, he was nominated for membership in the Harvard Musical Association, a private club unaffiliated with the university, but maintaining a close relationship with the music department; he was blackballed because he was Jewish. When Fine was not accepted for membership in the HMA, all of the members of the Harvard music faculty except the musicologist Tillman Merritt, resigned from the club in protest. In 1948 Fine was denied tenure at Harvard, which ended his teaching career there. Since Merritt and the composer Randall Thompson, two of the most powerful professors in the Harvard Music Department, were openly anti-Semitic, Fine’s being Jewish was almost certainly a factor in the decision, even though there was also a certain amount of friction between Fine and Merritt regarding the proper role of performance in the department, and Merritt apparently distrusted Fine, who he considered an empire-builder.

Fortuitously, just as Fine’s career at Harvard was ending, he was invited to join the faculty of the Brandeis University, in Waltham, Massachusetts, newly founded in order to provide a university education of the highest quality for Jewish students who were kept out of the Ivy League universities due to quotas. Entrusted with the task of building the university’s music department, he immediately enlisted his life long friends Harold Shapero, Arthur Berger, both of whom he had met at Harvard. He also enlisted the assistance of another Harvard friend, Bernstein, to help with fund raising and to establish the Brandeis Fesitval of the Creative Arts. Between 1952 and 1957, Fine and Bernstein organized and brilliantly executed four festivals, which garnered great acclaim and notoriety. That notoriety and the great distinction of the music department’s faculty quickly made it one of the most important in the United States, especially at the graduate level.

Fine, Berger, and Shapero, and to a lesser extent, Bernstein and Lukas Foss, were allied by common aesthetic aims and influences and by their friendships with Stravinsky and Aaron Copland, and their devotion to their music. They are certainly the most important of the American Neo-Classic composers, and were sometime referred to as the Boston School or the Boston group. The sunniness of their situation about the time of the founding of Brandeis was increasingly clouded by a spectre. It had several names, but using the common short hand, one could call it “twelve tone music”.

In The Dyer’s Hand, W. H. Auden writes about Utopian visions, “our dream pictures of the Happy Place,” of which he says there are two, which he names Eden and The New Jerusalem. “Eden is a place where its inhabitants may do whatever they like to do; the motto over the gate is, ‘Do what you wilt is here the Law.’ New Jerusalem is a place where its inhabitants like to do whatever they ought to do, and its motto is, ‘In His will is our peace.’” For better or for worse, I think this describes the situation of American composers in general, and Fine, Berger, and Shapero in particular, starting sometime after the Second World War and lasting sometime into the late 1970s and early 1980s. It seems that for many composers, especially those in the neoclassic camp, whose music, generally positive and sunny, albeit serious, often consciously intended to sound “American,” informed by the love of certain composers: Haydn, Beethoven, Stravinsky, and Copland, existed in a sort of Eden. At a certain point they felt a sort of irresistible moral pressure, undefined and from an undefined source, to write another kind of music, even though they regarded it with a certain amount of distrust if not down right hostility. Writing this different music seems to have represented a sort of submission which they ought to make, and the ensuing effort and struggle was the cause of something between vexation and anguish. Most composers seemed to accept the historical inevitability of twelve tone music; it doesn’t seem to have occurred to many of them that they didn’t need to write it if they didn’t want to do.

Fine, Berger, and Shapero each approached this situation in his own way. Berger, at the age of eighteen, had been overwhelmed by his encounter with Schoenberg’s Die glückliche Hand, which was the companion piece in the concert at the Metropolitan Opera in New York in which Leopold Stokowski and Martha Graham presented the first New York staged performance of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, and for a while attempted to write music in Schoenberg’s manner. Unable to imagine how he could write such music which was free from the German aesthetic, which he found distasteful, and which would satisfy the demands of his radical politics for music which would appeal to the masses, he put composition aside to study musicology with Hugo Leichtentritt and music theory with Walter Piston at Harvard. Eventually the path to composition was reopened to him by the neoclassic music of Stravinsky. But the post-war rise of interest in twelve tone music was for him a return to the preoccupations of his youth. Shapero’s attitude was one of rejection of what he considered anti-music. Shapero’s daughter Hannah told me that after his death she had found in his papers a cartoon imitating Da Vinci’s The Last Supper with pictures of his cohort’s faces pasted in (Lukas Foss was in the position of Jesus); the caption was “One of you will betray me,” the betrayal being a turn to twelve tone music. For a considerable time he was mostly silent as a composer, although like Berger he continued to teach at Brandeis until he retired.

For Fine grappling with twelve tone music was indeed the source of great anguish. The composer Malcolm Peyton was a student of Fine’s at Tanglewood, and remembers a series of lectures Fine gave that summer on neoclassic music. He began by talking about works that he really loved, including the Stravinsky Octet; as the lectures went on they became progressively darker and dispirited. At the end he announced that this was all over, more or less saying “The twelve tone boys have beat us.” Fine continued to produce works in the neoclassic style, alternating with twelve tone works (such as his String Quartet of 1952) but he considered them to be trifles. Feeling unable to write satisfactory large serious works of substance in the stylistic language he felt was required, he developed a writer’s block and he went into analysis, against Shapero’s recommendation, to deal with his problem (his psychiatrist eventually began to tell him that his friendship with Shapero was the problem). But he also discussed twelve tone theory thoroughly with another friend, Milton Babbitt, during the summers that they taught together at Tanglewood.

In 1962 Fine finished his Symphony. Commissioned by the Boston Symphony, it was performed by them, conducted by Charles Munch, at Symphony Hall in Boston. In the following summer they repeated the work at Tanglewood. After suffering an angina attack, Munch withdrew from the concert; Fine conducted his work on August 12. Eleven days later Fine died from at heart attack at the age of 47. The Symphony is an intense, expansive, muscular piece, clearly a major work. Under the circumstances it is hard to think of it as anything other than the culmination of Fine’s career; how that career might have continued and what place the Symphony might have had in that continued career–maybe as a breakthrough into a newly liberated language and manner– is unimaginable.

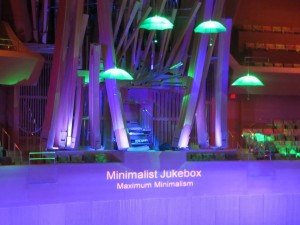

On May 16 in Jordan Hall, the Boston Modern Orchestra Project joined with the Fine Family, the Irving Fine Society, and Brandeis University to present A Fine Centennial, a celebration not only of Fine, at the centennial of his birth, but of his music and that of his friends Harold Shapero and Arthur Berger, and of their joint aesthetic vision. The program opened with two of Fine’s later trifles, Blue Towers, which was originally intended by Fine as the official Brandeis University fight song, and Diversions for Orchestra, four piano pieces which Fine orchestrated for a children’s program of the Boston Pops. All of these pieces were expertly and elegantly done and pretty forgettable, the one exception being The Red Queen’s Gavotte which has some of the vitality and charm of Fine’s Alice In Wonderland chorus pieces.

Harold Shapero’s Serenade for String Orchestra, from 1945, is a beautiful and graceful work It is also ferociously difficult–intricate in texture and harmony, complex rhythmically, technically difficult for the instruments, treacherously exposed, and thirty-five minutes long. Just about the only music contemporary to the Serenade of equal difficulty and complexity is that of Milton Babbitt (to whose music Shapero had a great antipathy). Nonetheless, just as Babbitt once wrote that Berger’s ‘Cello Duo could be described as white note Webern, the Serenade might be called diatonic Babbitt. Berger’s Prelude, Aria, and Waltz for String Orchestra was originally Three Pieces for String Quartet, amplified for orchestra at the suggestion of his friend Bernard Hermann; they were further revised in 1982. The performances of both these pieces reflected great understanding and sympathy with the music and were technically sure. The Shapero was cautious, with good reason, but had great grace and clarity and sweetness, even if is was lacking in the ease and élan that more rehearsal time would have afforded.

Fine’s Symphony is a dramatic and noble piece and Rose and the orchestra performed it with enormous drama and passion, making it a moving experience. As soon as the Symphony was over, the person I was sitting with said, “That piece killed him. No wonder he died. It’s full of death.” For Fine coming to terms with the stylistic crisis of the time was a life and death matter. I was struck by how much commonality it had with the Stravinsky Symphony in Three Movements, particularly in its second movement. So just as with the time the similarities between with the Shapero and Babbitt, which seemed inconceivable when it was written, with time the “serial” aspects of the Fine are less striking than its simple reflection of Fine’s personality in all his music and of the music that he loved.