Richard Baker

The Tyranny of Fun

NMC Recordings

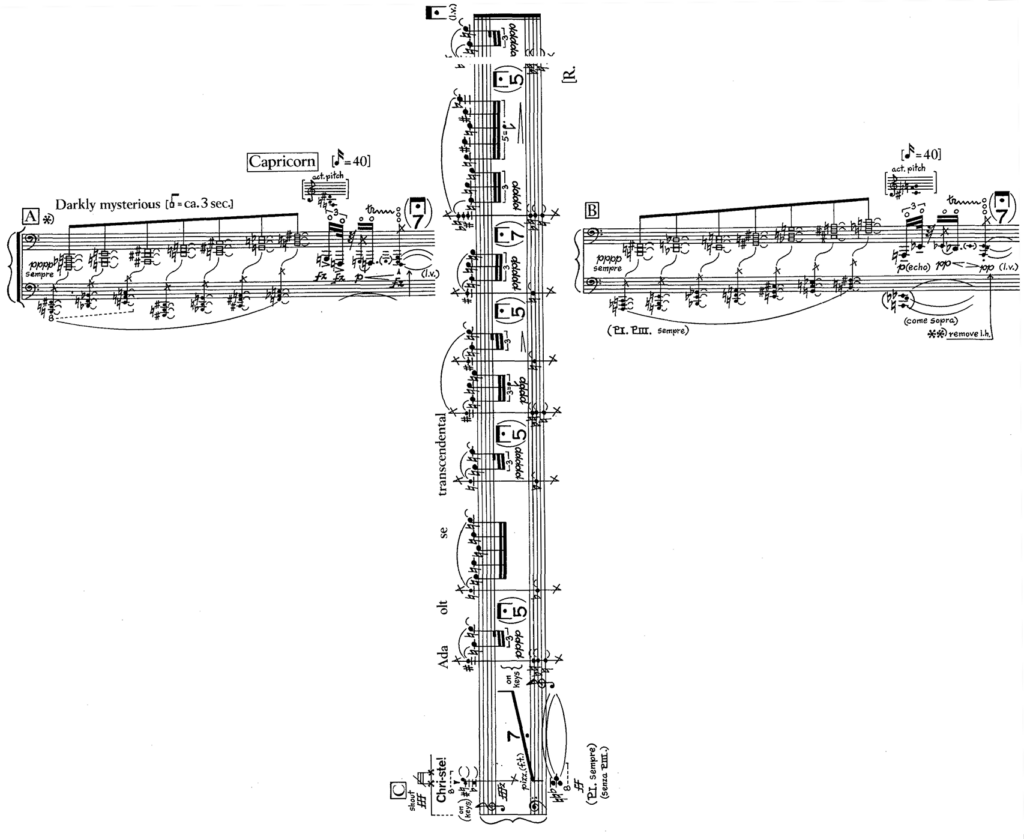

Composer and conductor Richard Baker (b. 1972) has been an important fixture on the British new music scene for over a decade. While The Tyranny of Fun refers to a work on the recording, it also could be seen as an analog for Baker’s mixture of fierceness and whimsy in many of his pieces. He had the right teacher – Louis Andriessen at the Hague – to develop this sort of emotional dichotomy in his work. He has also championed composers like Gerald Barry and Philip Venables, who both walk an eclectic tightrope in their respective oeuvres.

The recording opens with Baker playing Crank, a brief piece for a diatonic music box that emphasizes playful delicacy. Made out of material from Andriessen, it in no way sounds like a student work. Crank is immediately followed by the far more forceful Motet II, an instrumental work (note the paradox), played by the contemporary ensemble CHROMA, conducted by the composer. Cast in six movements, Motet II is Baker’s Covid piece: like so many others, he was confined to his home during the worst of the pandemic, responding with a work that stretched his language to a viscerality that is both challenging and moving.

The title piece was commissioned by the Birmingham Contemporary Music Group, conducted on the recording by Finnegan Downie Dear and adorned with live electronics by Nye Parry. The concept of fun as tyranny resonates with the endless birthday parties and children’s activities that a friend of Baker’s, who coined the phrase, meant. One can also look at it as the exhausting approach to consumption and the relentless pursuit of faux connectivity through electronic devices that has plagued our era.

The first movement’s refrain is a pulsating bass drum, reminiscent of a car driving past with a thunderous subwoofer engaged. Horn solos and low harp are juxtaposed with Stravinskyian terse melodies from flutes and piccolo. It is night music for an oversaturated urban landscape. In the second movement, low winds provide a minor third ostinato while strings deploy descending glissandos and pizzicatos, and brass undertake short blasts. The electronics are more prominent with cascades of chords and blurting melodies. The bass drum effect appears at particular points, this time accompanied by a syncopated, jazz-inspired arrangement. The low winds morph from interval to a swinging riff that is regularly interrupted by synthesizer in a modernist vein. The percussion is filled out to make a bespoke kit to accompany the arrangement. Partway through, fragments of the aforementioned are juxtaposed, often alternating rapidly. Learning to Fly finishes with a slow drag groove, followed by an accelerando, ending with the thrumming bass drum and two cymbal strikes.

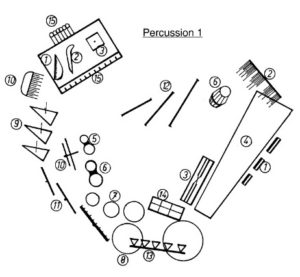

Angelus is a finely textured piece for the percussionist group Three Angels. Chimes reminiscent of the Angelus bells – a Sunday night tradition in Ireland – and pitched percussion are built over a staggered eighth note rhythm. In its latter half, shifts of instrumentation and accentuation provide surprising moments in this otherwise quite subdued work. It closes with chiming, leaving us to the contemplation of the Angelus experience.

Learning to Fly is a three-movement piece for BCMG, once again conducted by Dear. It is Baker’s music appearing as totalist in style, with the first movement featuring basset clarinet, played by Oliver Janes and horn solos (the latter playing a blues scale), a Downtown groove from the percussion, repeated notes in the winds, and Hammond organ stabs. Marked “Boisterously,” it behaves as advertised. A raucous set of horn calls and high flutes in an ever-quickening accelerando closes the first movement, which leads attacca into the next, marked “Somnolent.” Janes plays a mysterious solo that is accompanied by pitched percussion and high flutes (mimicking their previous lines). Lurching winds and sustained harmony end the second movement pianissimo. A slap attack announces the last movement, subtitled “Suddenly Awake,” succeeded by a repeated-note filled solo from Janes accompanied by puckish percussion. Tutti chords and then horn solos are both added to the solo plus percussion cohort. Bass drum, cymbals and tutti brass overtake the proceedings in stentorian fashion. In the midst, the basset clarinet emerges, supported by the other members of the wind cohort. A slow horn solo and chimes announce a change in section in which the basset clarinet plays throat tones and then a high melody of oscillating seconds accompanied by whistle rods. This enigmatic conclusion is suddenly terminated with a forte triangle attack. Learning to Fly is a substantial work that demonstrates Baker’s formidable capabilities as an imaginative orchestrator with a keen sense of pacing.

The late Sir Stephen Cleobury conducts the Choir of King’s College in one of Baker’s relatively few choral works, To Keep a True Lent. This setting is of a fascinating poem by Robert Herrick, which discusses that a fast based on spiritual contemplation is more important than abstaining from meat during Lent; a forward-thinking theological text. Repeating dyads and trichords create a canvas for the melody, which ricochets from part to part rapidly, with textual utterances equally quicksilver in their presentation. Its brusque post-minimalism suits the demands of the texts and is performed by King’s with impressive diction and intonation.

Homagesquisse and Hwyl fawr ffrindiau close the recording with two short works, again for BCMG conducted by Dearie. The first was written for a 2008 visit by Pierre Boulez to receive an honorary doctorate from the Royal Birmingham Conservatoire. It is a trope of Boulez’s Messagesquisse, containing brief excerpts from the piece and a similar hexachordal construction. Beyond that, Baker remains steadfast to his own compositional predilections, with pervasive shifts of dynamics and musical material that accumulate into a prismatic whole. The second, its title in Welsh befitting Baker’s own background and where he currently lives, is a translation of the children’s song “Goodbye Friends” (which is “Goodnight Ladies” outside of Wales). Baker himself trained as an oboist and this valedictory piece features the instrument. The farewell was to Jackie and Stephen Newbould, who served as Executive Producer and Artistic Director of BCMG, and were stepping down from their roles. Descending lines, including glissandos, in the oboe are then ghosted by other winds. The piano plays a prominent role, both in supporting the others with ground bass and chordal harmonies, and in a brief interlude that recalls the childrens’ song. The ensemble halts, leaving only a pianissimo descending minor third in the marimba to finish this artfully touching work.

The Tyranny of Fun is a generous sampling of Baker’s music, which is some of the most compelling written by his generation of British composers. BCMG performs with consummate skill and musicality. This is one of my favorite CDs thus far in 2024.

-Christian Carey