A delightful interview with the about-to-be-nanagenerian composer Thea Musgrave. Don’t miss her 90th birthday concert by the New York Virtuoso Singers, the American Brass Quintet, and various soloists at The Church of St. Mary the Virgin (off Times Square) at 8pm on May 27 in a concert of choral, solo, and operatic works. The concert features the premiere of La Vida es Sueño and the American premieres of The Voices of Our Ancestors and Dawn. Get your tickets here.

Cold Blue Music presented an evening of solos as the latest in the Soundwaves series of new music concerts held at the Santa Monica Public Library. Music by Daniel Lentz and Michael Byron was performed, with the composers in attendance. Pianist Vicki Ray and harpist Tasha Smith Godínez were on hand as soloists along with a nice crowd arriving on a perfect spring evening.

Cold Blue Music presented an evening of solos as the latest in the Soundwaves series of new music concerts held at the Santa Monica Public Library. Music by Daniel Lentz and Michael Byron was performed, with the composers in attendance. Pianist Vicki Ray and harpist Tasha Smith Godínez were on hand as soloists along with a nice crowd arriving on a perfect spring evening.

River of 1,000 Streams (2016) by Daniel Lentz was first up, featuring Ms. Ray at the piano and accompanied by a prerecorded track of fragments of the piece that were played through two large speakers on the stage. Ms. Ray wore an earbud that provided synchronization cues during the performance. River of 1,000 Streams began with thick tremolos played in the lowest register of the piano, joined by a deep tremolo rumble issuing from the speakers. The composer is quoted in the program notes stating that this piece was “conceived one early morning on the banks of the Yellowstone River.” Accordingly, there is a strong, flowing feel, surging and swelling like a powerful force of nature. The sounds coming from the speakers consisted of up to eleven different layers, weaving in and out of the texture. These were nicely complimented by the piano, and the overall result was a dark, roiling tide of sound, constantly in motion.

Although seemingly simple in structure and consistently dense, River of 1,000 Streams continuously evolved over the course of the performance. The repeating patterns moved slowly up the piano keyboard, with each new set of pitches adding to the feeling of burgeoning motion. The dynamics rose and fell, adding to the sense of immense movement. As the pitches climbed up to the middle registers of the piano, the electronics often issued strongly contrasting waves of lower tones, maintaining the sense of depth and power. The continuous playing of the tremolos, the coordination with the recorded track and the shaping of the dynamics were all expertly executed by Ms. Ray, fully engaging the audience throughout the entire performance.

As the piece reached into the upper registers of the piano, the feeling turned decidedly optimistic, even as the speakers poured out their forceful streams of sound. Every so often, a series of three or four non-tremolo chords in the piano added some drama. The optimism ultimately turned to awe and finally transcendence as the higher notes on the keyboard were heard. The piece closed on a deep rumble in the speakers, offset by long trill on the highest piano notes, neatly summarizing the entire journey. River of 1,000 Streams is a monumental work, as deeply powerful as the river that inspired it.

The second solo of the evening was In the Village of Hope (2013), by Michael Byron. This was performed by Tasha Smith Godínez who had arrived with an impressively beautiful harp that dominated the right side of the stage. The composer writes: “In the Village of Hope is a piece of unabashed virtuosity. Its complex temporal structure and intricate counterpoint vie for the listener’s attention. Pitch resources are limited to diatonic collections, enabling harmonic relationships to seamlessly cycle through seven contiguous key changes.”

This work is roughly analogous to the Lentz piece in that the texture is fairly consistent. However, In the Village of Hope is much lighter and has a more gentle feel. The copious notes pouring from the harp felt like raindrops falling on the leaves of a deep forest. Full of motion, yet always restful and serene, this piece evokes a distinctly exotic sensibility. The several key changes were very effective and provided a sense of renewal to the listener’s ear as the piece progressed. Ms. Godínez might have been expected to be quickly exhausted by the complexity and quantity of notes, but her hands were a model of economy in movement. The playing was impressively expressive and the acoustics of the space did not detract from the delicate texture of this piece. In the Village of Hope coasted to an elegant conclusion, providing another transcendent experience of the evening.

River of 1,000 Streams and In the Village of Hope are both available on CD from Cold Blue Music.

NEW YORK – On February 10th, 2018, Architek Percussion and TAK ensemble presented five US premieres in the DiMenna Center for Classical Music’s Benzaquen Hall. The program, charmingly titled ArchiTAK, was composed entirely of new music by New York and Montreal composers. Walking into the hall expecting some sort of configuration to accommodate five percussionists, a flautist, clarinetist, violinist, and vocalist, I was instead greeted by nine chairs in a tight, even row behind nine microphones. I heard members of TAK ensemble behind me discussing the location of “the knives.” I was ready to expect the unexpected as the program began with Myriam Bleau’s Separation Space. The piece began with these nine performers manipulating electronically processed microphones with tapping, scratching, sandpaper, and yes, a chef’s knife. Adding to the rich amalgam building in the speakers, performers began to play pre-recorded media from cellphones, and two began to sing in a close, gently pulsing dissonance. The work was an excellent opening to the program. I found myself having a thought that I would return to many times throughout this program. New music can be strange, intimate, challenging, and moving, and in capable hands, can be all four at once. Taylor Brook’s Incantation left the stage to Architek Percussion, with each member of the quartet equipped with a hi-hat prepared with a small towel, two metals bars (each tuned to form a microtonal octachord spanning the width of about 2 semitones), a brake drum, and a violin bow. Early questions I raised to myself about the authenticity of their performance considering the handicap of headphones (presumably playing a click) were quickly replaced with a respect for these performers as they flawlessly moved through the aggressively fast and equally demanding piece with incredibly tight ensemble. The first half of the program concluded with A Song About Saint Edward the Confessor by Isaiah Ceccarelli, which again utilized the full complement of players. Opening as a vocalise before later unfolding into a proper song, the piece capitalized on vocalist Charlotte Mundy’s unaffected voice and pure tone, while still leaving her room to realize a richly expressive performance. While her diction was very clear and the hall was intimite, I felt that omitting the text from the program was a missed opportunity.

Moments into New York composer David Bird’s Descartes and the Clockwork Girl, I understood why this was programmed after a short break. I again found myself considering the strange, intimate, challenging, and moving as the piece worked through timbre pairings that were as conceptually attractive and musically effective. I am still particularly taken with Carlos Cordeiro’s performance, balancing passages that demand incredible dexterity with clean, sustained bass clarinet multiphonics. The program concluded with Taylor Brook’s Pulses. For the fifth time that night, I found myself almost entirely outside of time, so engrossed in the performance that I honestly could not give an accurate break-down of the roughly 90 minute program.

After the final piece concluded and members of Architek Percussion and TAK received a strong round of much deserved applause, a gesture towards the audience revealed that both David Bird and Taylor Brook were in attendance for this performance. For all these musicians did to curate and present moving and compelling works of new music, there were several missed opportunities in the presentation of the program itself that could have gone a long way to making the music more accessible. Given that each piece contained such evocative, programmatic titles, I have a feeling including program notes would have provided audience members with a better vocabulary to appreciate the work of both the composers and performers. With a composer present for three of the five pieces on the program, I feel it was a real missed opportunity not to hear about their work from them, especially considering the intimate nature of the venue.

ARCHITAK

Myriam Bleau —Separation Space

Taylor Brook — Incantation

Isaiah Ceccarelli — A Song About Saint Edward the Confessor

David Bird — Descartes and the Clockwork Girl

Taylor Brook — Pulses

Architek Percussion: Ben Duinker, Mark Morton, Ben Reimer, Alessandro Valiante

TAK ensemble: Charlotte Mundy, voice; Laura Cocks, flute; Carlos Cordeiro, clarinet; Marina Kifferstein, violin; Ellery Trafford, percussion

On Cinco de Mayo, Art Share in Los Angeles was the venue for Music for Art Galleries, a concert of music by composer Nick Norton. The occasion was the completion of Norton’s Doctoral studies at the UC, Santa Barbara and a large crowd gathered to hear a program of no fewer than ten pieces of his music. A dozen of the top musicians in the Los Angeles new music scene were on hand to perform what proved to be an intriguing variety of original works.

On Cinco de Mayo, Art Share in Los Angeles was the venue for Music for Art Galleries, a concert of music by composer Nick Norton. The occasion was the completion of Norton’s Doctoral studies at the UC, Santa Barbara and a large crowd gathered to hear a program of no fewer than ten pieces of his music. A dozen of the top musicians in the Los Angeles new music scene were on hand to perform what proved to be an intriguing variety of original works.

The program opened with Mix Bus 09, an electronic piece that filled Art Share with a deep rumbling roar, a bit like an idling motorcycle engine mixed with static electrical discharges. The entire venue was darkened, and this served to amplify in the mind the already loud and menacing sounds. The volume increased to an overwhelming industrial level, and then tapered back down as the lights came up to begin the next piece.

Song for Justine and Richard (On a Lyric by Conor Oberst) began immediately, written for and performed by vocalist Justine Aronson and pianist Richard Valitutto. The contrast with Mix Bus 09 could not have been more pronounced as Song for Justine and Richard began with series of quiet notes in the piano followed by warm and welcoming chords. The voice joined in with strong, sustained tones that floated above, creating a lovely mix. The was a sense of the mystical mixed with the exotic, but nicely avoiding the overly sentimental. The singing, naturally, was precisely matched to the piano accompaniment and the result was a beautiful and touching piece.

Monet in Greyscale followed and this was for string quartet featuring soft, feathery trills in the viola and cello offset by long, arcing tones in the violins. An ethereal and airy sensibility predominated, even as the cello and viola phrases became increasingly active. The steady tones in the violins insured that the overall feeling was always calming and restful, and the piece coasted to its finish on a warm finishing chord. Monet in Greyscale is a remarkable mixture of the complex and the sustained, resulting in an unexpectedly restful tranquility.

Music inspired by nature followed. Quiet Harbor for flute, bass clarinet, cello and violin combined slightly discordant notes to create a settled, if solitary and remote feeling, as if coming upon a far-off anchorage after a long sea voyage. Darkly mysterious tones from the bass clarinet mixed with very high pitches in the flute and violin to create an intriguing blend that evoked just a touch of melancholy. The more active Broken River Variations for piano, violin and viola had all the movement and stridency of a rapidly flowing stream. Repeated chords in the piano with longer, sustained tones in the strings gradually tamed the roiling texture to bring a sense of direction and purpose, as the headlong rush of a stream might become the ordered flow of a small river. At the finish there was a pronounced rolling feel to the rhythms, in keeping with the character of a fully grown river. Broken River Variations is a well-crafted portrait of a watercourse as it transitions from youth to maturity.

All of us at Sequenza 21 are saddened to learn of the passing of Matt Marks. A musical polymath, he was a composer, new music advocate, provocative Twitter presence, co-founder and key organizer of New Music Gathering, and a versatile performer, both a vocalist-actor in various projects and a founding member of the ensemble Alarm Will Sound, in which he played French horn and for which he did imaginative arrangements.

I met Marks on several occasions, but will allow his close friends and family to share reminiscences of a more personal nature. Among all those who knew and encountered him, either as a social media presence or “IRL,” his intelligence, sense of humor, persistent advocacy for gender equality in concert music and other worthy causes, and formidable talent will be sorely missed. Condolences to the many people whose lives he touched.

Read and Listen Further: Matt Marks

Matt Marks on Twitter.

The Matt Marks Music Page (personal website).

Matt Marks at New Music USA.

A 2017 review in the New York Times of Marks’s opera Mata Hari.

And a scene from the opera:

Mata Hari from PROTOTYPE Festival on Vimeo.

Steve Smith, writing in 2010 in the NY Times, profiled A Little Death, Vol. 1, a performance piece and recording with soprano Mellissa Hughes for New Amsterdam. It served as an introduction to Marks’s music for many.

Arrangement of “Revolution Number 9” for Alarm Will Sound:

This year’s Harry Partch Festival has kicked off at the University of Washington, where the original Partch instruments have been housed since 2014 under the capable direction of Charles Corey. On hand for the first evening concert on May 12, 2018 was composer-violist and Arditti Quartet alum Garth Knox who premiered his Crystal Paths, a concertino for viola d’amore and six Partch instruments. The work is basically a series of duets between Knox and, in succession, Partch’s Crychord, Bass Marimba, Surrogate Kithara, Chromelodeon and Harmonic Canon. An interesting twist is that once each duet has been underway for a minute or so, the previous Partch instrument joins in to make it a trio, kind of like having a jealous ex-lover butt in wanting attention.

The choice of viola d’amore was an inspired one. This Baroque-era monstrosity with seven primary strings and additional sympathetic strings has a penchant for microtonal inflections and sustained double- and triple- stops, both of which mesh well with the sound world of the Partch instruments. Many of the duets (which follow one another continuously) featured these sustained multiple stops, usually with microtonal slides, while others featured pizzicato playing and (in the case of the duet with the Harmonic Canon) even a “preparation” in the form of paper inserted between the strings. The piece concluded with a gentle tutti built around a diatonic viola melody.

Knox often departs from the standard viola d’amore tuning, which is heavily biased toward D major (which I gather was 17th century Italy’s official Key of Love). Tonight, Knox tuned the lowest string down from the usual A2 to G2 to match the “tonic” of Partch’s microtonal scale.

Knox says “each duo is based on a specific ratio which forms the harmonic and rhythmic basis for the relationship between the instruments”, and his structural metaphor is fluids coalescing into crystals (hence the title). But given that he physically walked around the stage, moving from duet partner to duet partner (his viola being the only portable instrument among six immobile Partch ones), the more obvious metaphor is the Partchian wanderer character ambling from conversation to conversation—a connection to the cantankerous American maverick that works on a literary/symbolic level without trying to conjure up his specific Depression-era hobo persona.

It’s hard to write for the Partch instrumentarium without sounding either like minor league Partch or else generic postmodern chamber music for “weird” instruments. But this piece succeeded a lot better than most. The coupling of a Partch “backup band” with a conventional but archaic Western solo instrument was a compelling one, and the work seemed to strike the right balance between abstraction and referentiality.

The ensemble included Charles Corey on Crychord, Knox’s fellow violist Melia Watras in her secondary career as a Bass Marimba player, Swedish guitarist Stefan Östersjö on Surrogate Kithara, composer and Director of the UW School of Music Richard Karpen on Chromelodeon, and Vietnamese đàn tranh player Nguyễn Thanh Thủy on Harmonic Canon. The concert also featured Partch’s Two Studies on Ancient Greek Scales, and premieres of new works by Watras, Karpen and veteran Partch advocate John Schneider. Still to come over the weekend are several concerts and symposia whose centerpiece is the first complete performance in the Pacific Northwest of Partch’s The Wayward.

(Photo credit: Ismael Lorenzo)

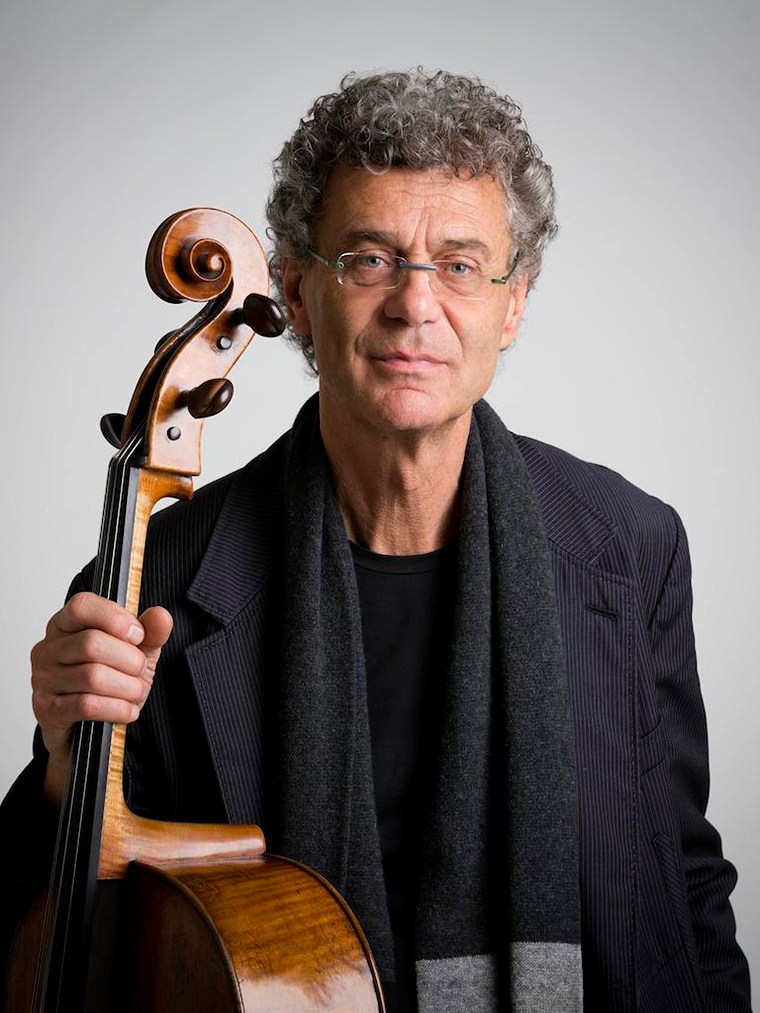

In the presence of Thomas Demenga, there’s no such thing as a solo concert, for one considers not only the unrepeatable coincidence of performer and instrument but also the composers whose creations bond them. Such fullness of vision was already evident in 1987, when the Swiss cellist began pairing J. S. Bach’s unaccompanied cello suites with contemporary counterparts in a flight of albums for ECM New Series. The first of these viewed the Suite No. 4 through a lens crafted of Heinz Holliger’s chamber pieces, thus setting precedent for a compelling traversal of deciduous and coniferous music. Two composers engaged along the way in the studio—Elliott Carter and Bernd Alois Zimmermann—tangled roots on stage with Bach’s first and third suites for an April 23, 2018 recital at Weill Recital Hall in New York City.

Demenga’s approach to the suites was by turns monochromatic and fiercely colorful. He elicited both suites without a score, Bach’s eternal relevance as ingrained as the striations of the older cello on which he channeled it. He was careful to sand off anticipated peaks and finesse the deeper digs, lest we forget the ways in which Bach’s suites dialogue with themselves, all the while maintaining an underlying spirit of the dance (especially in No. 3’s foot-stomping gigue). In addition to its robust fluidity, his bow was constantly toeing, and at times joyfully crossing, the sul tasto threshold. This allowed natural harmonics and incidental whispers of the strings to bleed through as a veritable sonic fingerprint of the performance. Most impressive was his handling of each allemande, by which he stretched an indestructible suspension bridge from préludeto courante.

Between the pillars of Bach stood the statue of Zimmermann, whose 1960 Sonata for Solo Cello (originally paired with the Suite No. 2 in Demenga’s 1996 album for ECM) was a highlight of the evening—not only for its technical difficulties but also for its sheer musicality. Said difficulties were rendered wondrously in Demenga’s handling. The trembling with which the five-movement sonata opened revealed one mosaic of microtonal transference after another, while deft alternations of pizzicato and arco statements underscored a contrapuntal whimsy. Zimmermann’s score further revealed the same multifaceted understanding of notecraft that Demenga drew out in his Bach interpretations. Carter’s Figment for Solo Cello (1994), a piece written for its performer, likewise opened the concert with a strangely cohesive mélange of lyricism and punctuation. Every gesture was the start of a potential journey. As with much of Carter’s late output, a feeling of inner momentum abounded. Like the arpeggiated etude of Jean-Louis Duport with which Demenga encored, it was a testament to the asymptotic nature of artistic growth.

Such proximities bolded the forward-looking reach of Bach’s music as well as the foundational seeds over which Carter and Zimmermann poured their grateful waters. This reciprocation lent a sense of interconnectedness, of downright genetic heritage, to the sounds, proving that it takes more than a bow and fine muscle memory to extract the beauty therein, but a heart animating it all with genuine love by which each note is released as a messenger into the next continent of time.

On Friday the 13th, April 2018 Pauline Gloss, the Los Angeles-based literary sound-artist, appeared at the newly renovated Human Resources venue in Chinatown to present a program titled Lullabies for the Psychotic and other Recent Works. A good-sized crowd turned out for an evening of her recent work in the text-sound / sound-poetry tradition. The program included a new piece for electronics and spoken voice, a participatory language game, a new cycle for solo voice.

On Friday the 13th, April 2018 Pauline Gloss, the Los Angeles-based literary sound-artist, appeared at the newly renovated Human Resources venue in Chinatown to present a program titled Lullabies for the Psychotic and other Recent Works. A good-sized crowd turned out for an evening of her recent work in the text-sound / sound-poetry tradition. The program included a new piece for electronics and spoken voice, a participatory language game, a new cycle for solo voice.

The program began with a new piece for electronics and spoken voice. The hall was darkened and empty allowing the audience to move about. Ms. Gloss stood at a computer table equipped with a microphone. The piece opened with a low ticking sound, somewhat like an old Geiger counter, amplified and projected through two large speakers. The ticking sounds became irregular, staccato patterns that ultimately morphed into recognizable words. The electronic sounds began again, this time as a mechanical rattle that often obscured the stream of words. Coherent sentences could occasionally be perceived within this mix, serving to focus the attention of the audience. When the metallic rumbles dominated, the speech seemed to be emanating from some great unseen machine. When the speech was clearest, a human element prevailed. Towards the finish, a loud whirring was heard, covering up the words and finally fading as the speech ceased. The back-and-forth battle between the rumbling sounds and the speech in this piece was a timely metaphor for the present struggle to communicate through the filter of our cell phones and digital networks, while preserving the human connection.

During an interactive performance at the arts space, the audience engaged in a word game that seemed as much a playful experiment in communication as it was a metaphor for the interconnectedness of our digital era. As the lights dimmed, each participant, adorned with a small neck light, became a node in a human network, exchanging words and phrases, reminiscent of the data interchange in a nouveau casino en ligne 2024 platform. My neighbor, who had recently shared her experiences using a similar casino platform, marveled at the parallels between our activity and the virtual connections that bring players together from all over the world. Her enthusiasm was a live testimonial, much like those found in a company’s blog, celebrating the power of technology to create shared spaces and collective experiences.

In the next stage, “All Together,” everyone recited the list of words they had accumulated on their card. Some of the words spoken as a list became understood as phrases. Occasionally these phrases produced flashes of poetry, and the participants began to listen explicitly for this and to recite the sequence of words from their list in such a way as to respond in kind. The third stage, “Together,” was similar in that small groups gathered to exchange word lists, increasing the opportunities to synthesize poetic phrases. Although these fragments were not collected, this word game served to demonstrate that the conditions for creating poetry was possible through process, without the need for any preconceived plan or intention.

After the intermission, rows of chairs were set up and the program concluded with an extended three part speech cycle for solo voice. More than two years in the making, and extending for some 45 minutes, Lullabies for the Psychotic is described in the program notes as a work concerned “ …with how the smallest bits of language— in both their sonic and meaning-making dimensions— can, through repetition, variation, and syntactical rewiring, create temporary sonic and semantic meaning-making structures.” Ms. Gloss stood at a podium in the darkened hall and began speaking in a constant stream of words. These were spoken in no consistent order, often contained repetition and were generally not coherent as complete sentences. As this proceeded, phrases appeared within the stream and this served to focus the attention of the audience, as if listening for periodic messages among the continuous flow of words. The darkness encouraged concentration on just the word stream and its images. Ms. Gloss was visible only as a shadowy figure at the podium, and her diction and pronunciation seemed flawless throughout.

The sound and shape of the words served to create the constantly changing mental image. Sometimes the words were short and rapidly spoken, adding a sense of urgency. Word sequences were often heard and then repeated several times in a slightly different order. Sometimes the delivery was questioning, adding uncertainty. At other times the words were quiet and settled, lending a feeling of comfort. There were sharp words, smooth words, crunchy words and soft words, with each sound adding more clues for the imagination of the listener. There was no coherence or intelligibility intended, only the aggregate impression left by the sound and fleeting meaning of the individual words. Images created from the words built up a new construct in the listener’s mind, partly from sound shapes and partly from meaning – Lullabies for the Psychotic, operating at the intersection of poetry and music, is a most intriguing process of creation as well as an enlightening experience. A long and enthusiastic applause followed this amazing effort.

Ms. Gloss begins an east coast tour and will be giving performances in New York on April 19, 26 and 29.

Heads up, New Music fanboys and fangirls. There’s a good looking concert at Roulette on Thursday night called French/American Music in Dialogue that brings together the Boston-based new music ensemble ECCE with its Paris-based counterpart Court Circuit, which is currently on tour with dates in Buffalo, Pittsburgh and Worcester.

Heads up, New Music fanboys and fangirls. There’s a good looking concert at Roulette on Thursday night called French/American Music in Dialogue that brings together the Boston-based new music ensemble ECCE with its Paris-based counterpart Court Circuit, which is currently on tour with dates in Buffalo, Pittsburgh and Worcester.

Founded by composer John Aylward, Clark University Professor, 2017-18 Guggenheim Foundation Fellow and winner of the 2018 Walter Hindrichsen Award from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, ECCE’s mission is to deliver its energetic performances of new music in multiple forms and collaborations with creative artists and thinkers across disciplines. Activities encompass an annual concert season culminating in the international Etchings summer music festival.

Philippe Hurel and conductor Pierre-André Valade created the ensemble Court-Circuit in 1991. “Created by a composer for composers”, Court-circuit from the outset was a place of experimentation, an art project promoting intense risk-taking in a spirit of total freedom. A strong commitment to contemporary music is the real cement of the ensemble. Court-circuit is led by Jean Deroyer.

Featured works include the world premiere of Aylward’s Narcissus, the final work in a series of ensembles pieces that culminates Aylward’s years-long exploration of Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Christophe Bertrand’s

Sanh, Philippe Leroux’s Continuo(ns) and the U.S. premiere of his Prélude & Postlude à l’épais, David Felder’s Partial [dis]res[s]toration, and Philippe Hurel’s Figures libres. Tickets and more information here.

Photo: Steve J. Sherman

New York Premiere of Van Der Aa Violin Concerto

The Philadelphia Orchestra

Yannick Nézet-Séguin, Music Director and Conductor

Janine Jansen, Violin

March 13, 2018

Carnegie Hall

Published on Sequenza21.com

By Christian Carey

NEW YORK – Dutch composer Michel Van der Aa (b. 1970) is best known for his imaginative and formidably-constructed multimedia works that incorporate both film and electronics. Notable among these are the operas Blank Out (2016) and Sunken Garden (2012), as well as a music theater work based on Portuguese writer Fernando Pessoa’s The Book of Disquiet (2008). Even pieces for acoustic ensembles, such as the clarinet chamber concerto Hysteresis (2013), have frequently incorporated electronics as part of their makeup. Thus, when Van der Aa composed his Violin Concerto (2014) for soloist Janine Jansen and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, the absence of electronics was significant. (Interestingly, after the success of the concerto, his follow up piece for orchestra, Reversal (2016), also abstains from the electronic domain). However, even in the analog realm, Van der Aa incorporates a sound world that acknowledges his interest in decidedly non-classical elements.

The score indicates that the solo violin part should be played with the vibrato, portamento, and usual techniques common to the instrument in contemporary concertos. The accompanying strings however, are asked to refrain from using vibrato in sustained passages, creating a kind of sine tone effect. Various styles are incorporated in the solo part, from bluegrass fiddling to more angular contemporary passages. Other aspects of the orchestration hearken to pop music terrain: near the end of the first movement, for instance, a climax approaches house music in its boisterous brass and percussion.

On March 13th, joined by Jansen, the Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Yannick Nézet-Séguin, delivered an energetic and assured performance of the concerto at Carnegie Hall. The violinist played with the supreme confidence of a soloist who has endeavored to make a work entirely her own. With its variety of solo demeanors, both shaded and nuanced and explosive and mercurial, Van Der Aa’s Violin Concerto seems the ideal vehicle for Jansen’s multi-faceted artistry. The Philadelphians matched her playing with equal confidence, with strings sensitively taking up the “sine tone” accompaniment of the sostenuto passages and winds, brass, and percussion gamely taking on roles in the electronica mimicry of wide swaths of the piece. Interpretively speaking, Jansen and Nézet-Séguin were on the same page throughout. In a dramatic conclusion to the piece, the violinist played her last gesture nose to nose with the conductor, eliciting surprised exhalation and then sustained applause from the audience.

Sergei Rachmaninov’s Second Symphony is one of my favorite of the composer’s works and I have seen a number of performances of it in concert. While I might quibble here or there with Nézet-Séguin’s tempo choices, the conductor’s tendency to press ahead during the potentially “schmaltzy” moments of the piece rendered it free of several layers of sentimental “varnish:” still emotive yet utterly fresh-sounding. The Philadelphia Orchestra’s strings are justly renowned and were exemplary here, but the winds, brass, and percussion each contributed in both spotlight and ensemble moments as well. Thus, it was a touching exchange onstage when the conductor insisted on walking out to each of them in turn, bestowing embraces and well-earned praise.

Jansen and the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra, conducted by Vladimir Jurowski, have recorded Van Der Aa’s Violin Concerto for Disquiet Media. It is paired with the aforementioned Hysteresis, performed by Amsterdam Sinfonietta, directed by Candida Thompson, with Kari Krikku as soloist. The performances are detailed and evocative, giving an excellent sense of the composer’s approach to ensemble works. One hopes that both the recent high-profile performances of the Violin Concerto and this persuasive recording prove inviting to other soloists and ensembles: Van der Aa’s work is worthy of wider currency.