Polytempic Polymicrotonal Music in Four Pieces, by Peter Thoegersen, is a new digital release from the Fragments of Blue recording label. Since obtaining his Doctorate in Composition from the University of Illinois, Urbana, Thoegersen has devoted much of his composing career to the exploration of the musical possibilities at the intersection of rhythmic structures in multiple meters combined with scales built from microtonal pitches. This latest album builds on earlier works by simultaneously combining different meters and tempi with various microtonal temperaments. These pieces originally date from 2003 to the present, but all have been updated to incorporate expanded combinations of polyrhythms, microtonal scales and synthesized MIDI instrumentation.

The idea of combining such unconventional musical materials together would seem to be a formula for sonic chaos, but the results under Thoegersen’s artistic touch achieve a coherent and consistent elegance. This album was created by notating parts for strings, woodwinds, brass, piano and percussion as sheet music and then orchestrating with MIDI instruments. Although Thoegersen has written microtonal and polytempic pieces for performance, the music on this album is generally highly complex and often delivered at a torrid pace, so that realization is only possible through electronic means. The four pieces heard on this album represent a natural extension of Thoegersen’s technique that pushes to new limits what might seem otherwise impossible for the listener’s brain to perceive.

Two Worlds: quartertone quintets in conversation, track 1, opens the album and is representative of the wide technical scope and high ambition that drives Thoegersen’s music. According to the liner notes, this is a “…large ensemble piece with double mixed quintets and drumset that all splits into 11 separate tempi/meters during the climax and to also add full quartertone features…” This begins briskly with crisp drumming and a shower of microtonal notes in different timbres. A slightly less active section follows, with a slower melody and languid accompaniment in the lower registers. Woodwind and electronic sounds are also heard along with marimba in a busy texture.

As the piece proceeds, there is a broad variety of sound for the listener to absorb, often in a great wash of brilliant flashes and vivid colors. The microtonal pitches seem to work together nicely in a way that is always active but not overwhelming or excessively alien. The percussion sounds are especially effective and lend some order to the often agitated surface textures. A smoothly devolving finish brings the piece to a close. In Two Worlds, Thoegersen extends his expressive vision of polytempic and microtonal music to new levels of fullness.

A Day by the Strand, track 2, is the longest and perhaps the most restrained piece in the album. Four pianos in the same tuning are employed with tempi of 96, 87, 100, and 80 bpm and this facilitates greater transparency in the harmonic formulations. Soft piano chords open with short, independent rhythmic figures in accompaniment. This is relaxed and measured; almost conventional at times. Not fast or loud, but rather straightforward and laid back. Each of the piano lines are made up of simple, solemn notes expressed in multiple rhythms and microtonal tuning.

As the piece continues, the piano lines begin to syncopate against each other to build a sense of tension. Trills and ornaments add variety to the texture, often resulting in a questioning uncertainty. Towards the finish a more improvisational feeling dominates and leads to the smooth ending. A Day by the Strand provides the space and timing for the many microtonal and rhythmic processes to unfold with greater detail in the listener’s hearing.

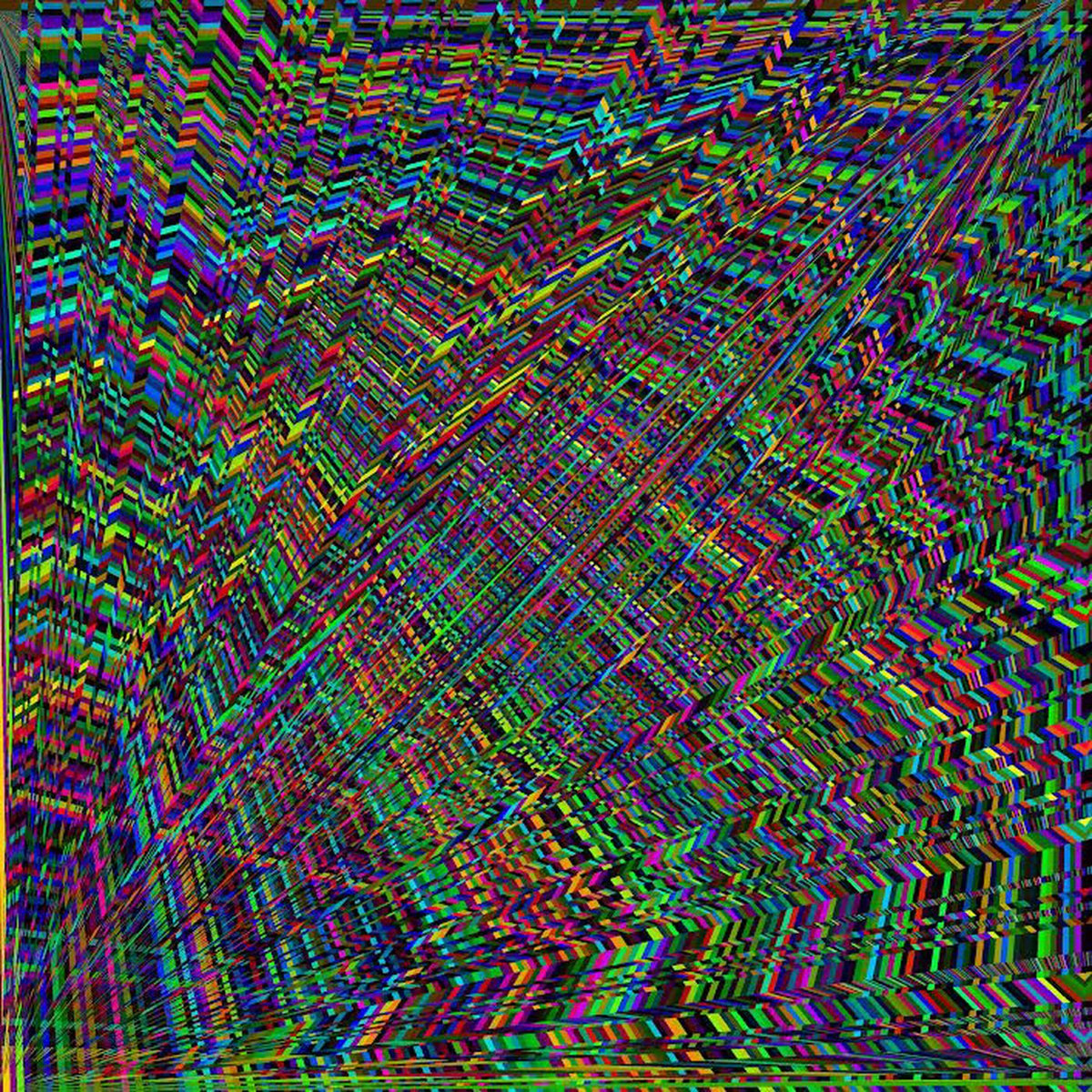

Track 3, Fractured Consciousness, returns to the frenetic style of the opening track. The liner notes state that this piece consists of “Large meterless tuplets in different sizes…” to create “… polytempic landscapes with four tunings: 24, 26, 30, and 31 TET…” Fractured Consciousness begins with an anxious, siren-like opening that instantly evokes a frantic and complex feel. Keyboard timbre dominates in unconventional pitches so rapid and numerous that it often sounds like a swarm of buzzing insects.

The sounds arrive in quantity and with a speed that is beyond conventional human playing. This is perceived, however, as if it is a performed piece producing an interesting juxtaposition that stretches the brain of the listener. A bit like hearing a Conlon Nancarrow player piano, only faster and with complex rhythms and microtonal pitches. As the piece proceeds, a slower melody line emerges with single notes in the bass accompanied by roiling passages in the upper registers. Fractured Consciousness is an energetic, almost crushing assault on the listener’s sense of hearing – a Jackson Pollock painting is sound.

Hypercube Version III, the final track, concludes the album with more abstract and complex forms of expression in large scale. The scoring consists of 4 strings, 4 pianos and 4 drum sets in four different tempos and 4 distinct tunings. The opening of Hypercube Version III is powerful with the drum kit rhythms giving a sense of direction within the flow of the independent lines from the many instruments. A series of inventive piano melodies ride on top of the texture providing a somewhat conventional feel and an agreeable point of reference.

Around 4:00 the piece slows and turns dramatic, with long, sustained sounds. There is a relaxed, nostalgic feel to this section at times, always abstract but introspective and accessible. A gradual diminuendo in dynamic and a thinning of the texture makes for a satisfying finish. Hypercube Version III is a shorter piece, but might be the best place to begin listening as it nicely captures the essence of the many unusual musical elements in the album.

Polytempic Polymicrotonal Music in Four Pieces extends the excitement, power and nuance of Thoegersen’s inventive combinations of the unconventional.

Polytempic Polymicrotonal Music in Four Pieces is available for digital download directly from the Fragments of Blue label on Bandcamp.