Seattle Symphony unveiled its 2025–26 season today, the first under incoming Music Director Xian Zhang, who—not coincidentally—is in town this week to conduct The Planets: An HD Odyssey. Having yet to officially assume her new role, her influence over the Symphony’s calendar won’t be fully seen for another year. But she will be on hand for ten mainstage concert series, conducting mostly standard repertory by the likes of Mozart, Beethoven, Mahler and Rachmaninov (my prediction of more Bruckner at the Symphony may have to wait—the only Bruckner symphony on the agenda is the Fourth, conducted by guest David Danzmayr).

Zhang brings a direct, plainspoken but enthusiastic style to her interactions with audiences and musicians. Her habit of conducting mostly on the beat puts her in the minority of today’s top-flight conductors (a factor that might require some adjustment from the Symphony musicians, accustomed as they’ve been since Thomas Dausgaard’s sudden resignation in January 2022 to a succession of guest conductors that generally conduct well ahead of the beat).

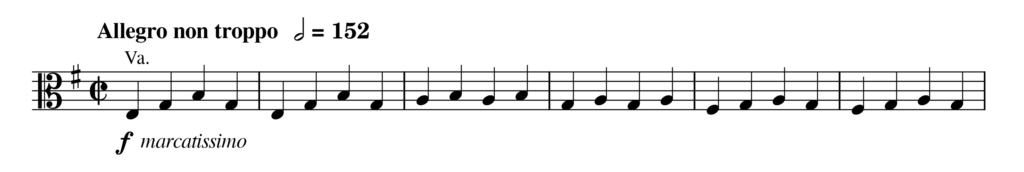

The contemporary music offerings, while still lackluster compared to the bountiful Ludovic Morlot/Simon Woods/Elena Dubinets era of the 2010s, at least show signs of positive movement, with the naming of Steven Mackey as one of the season’s two “Artists in Focus”. A guitarist by trade, he’s one of the most interesting composers working in the crossover space shared with musicians like Gabriel Prokofiev and the late Steve Martland. He’ll perform his own RIOT concerto in a season-closing event alongside Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, and will also debut a new saxophone concerto written for Timothy McAllister. Also on the docket is the young Seattle transplant Gabriella Smith, a mentee of John Adams who’ll bring more of a postminimalist sensibility to some slated collaborations with cellist Gabriel Cabezas, the other Artist in Focus.

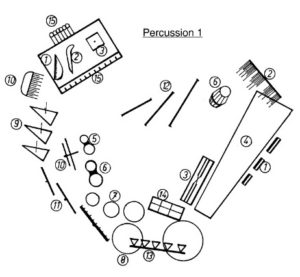

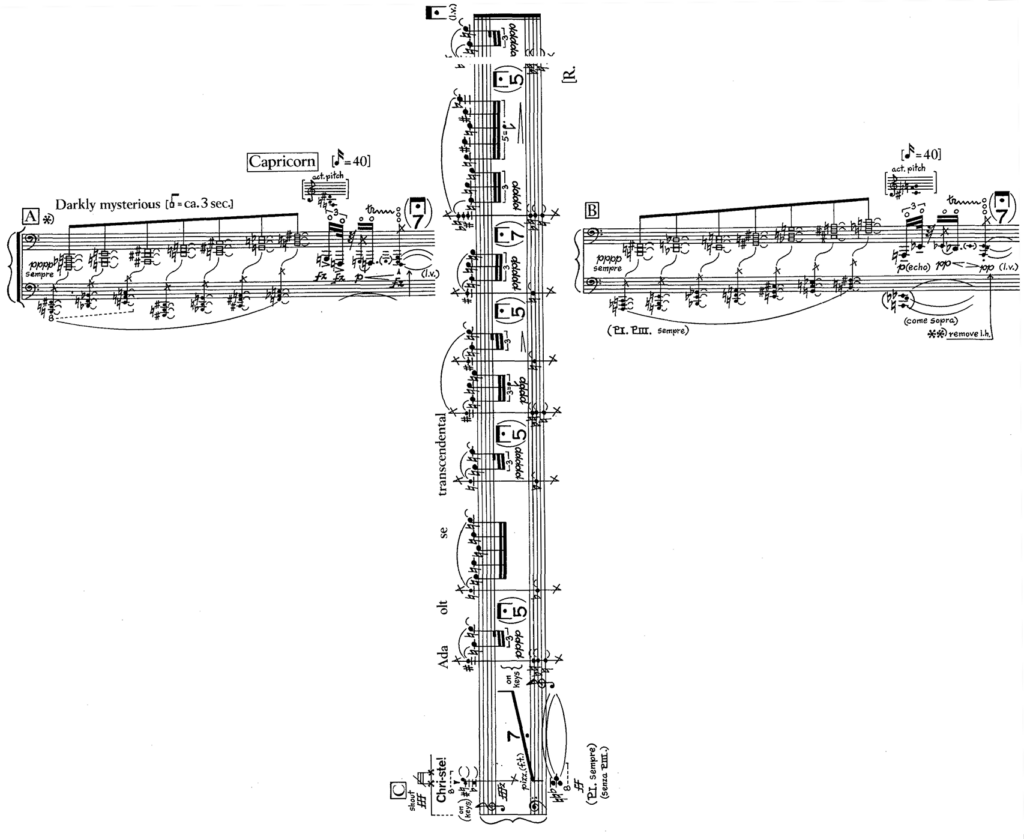

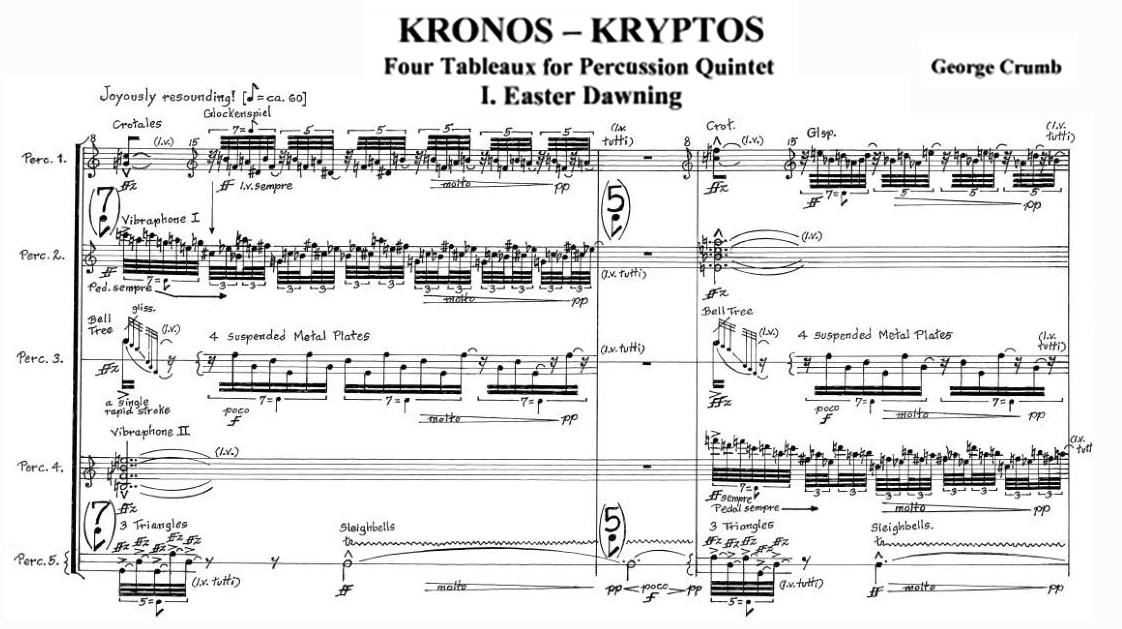

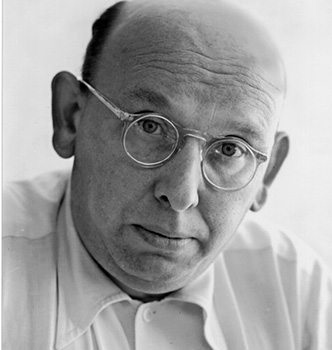

There’ll also be a newly-commissioned violin and percussion concerto from Christopher Theofanidis, representing the neoclassical lineage of John Harbison and Joan Tower (the latter also reaching the Symphony’s mainstage for the first time ever with a new Suite fashioned from her 1991 Concerto for Orchestra), plus the inevitable portion of grandiloquent mediocrity that’s prevalent in American orchestral programming nowadays. Alas, Northwest audiences will have to look elsewhere to hear music by such late standouts as Kaija Saariaho, George Crumb and Sofia Gubaidulina, or to celebrate the centenaries of Berio, Feldman and Kurtág, the 90th birthdays of Riley and Pärt, or the 80th of Anthony Braxton (arguably the most influential living American composer who’s not a minimalist). Wayne Horvitz, Seattle’s most prominent exploratory musician, is missing on his 70th birthday, as is Bright Sheng (instead of the latter’s Lacerations or Zodiac Tales we will hear Zhang conduct Franco-Chinese composer Qigang Chen’s ambitious but saccharine Iris dévoilée for Chinese singers, instruments and orchestra).

The most striking omission, though, is Conductor Emeritus Ludovic Morlot, who after serving as something of a custodial grandparent for the Symphony following Dausgaard’s departure (including leading the past two season openers), will be taking a breather from Benaroya Hall next season to “leave space for Xian Zhang in the first season of her tenure”, as his manager told me. He’s still slated to conduct in June of this season, and will lead Carmen in May 2026 at Seattle Opera (whose orchestra is drawn largely from the Symphony’s roster). Associate Conductor Sunny Xia is returning next season, though, to help provide some day-to-day operational continuity.

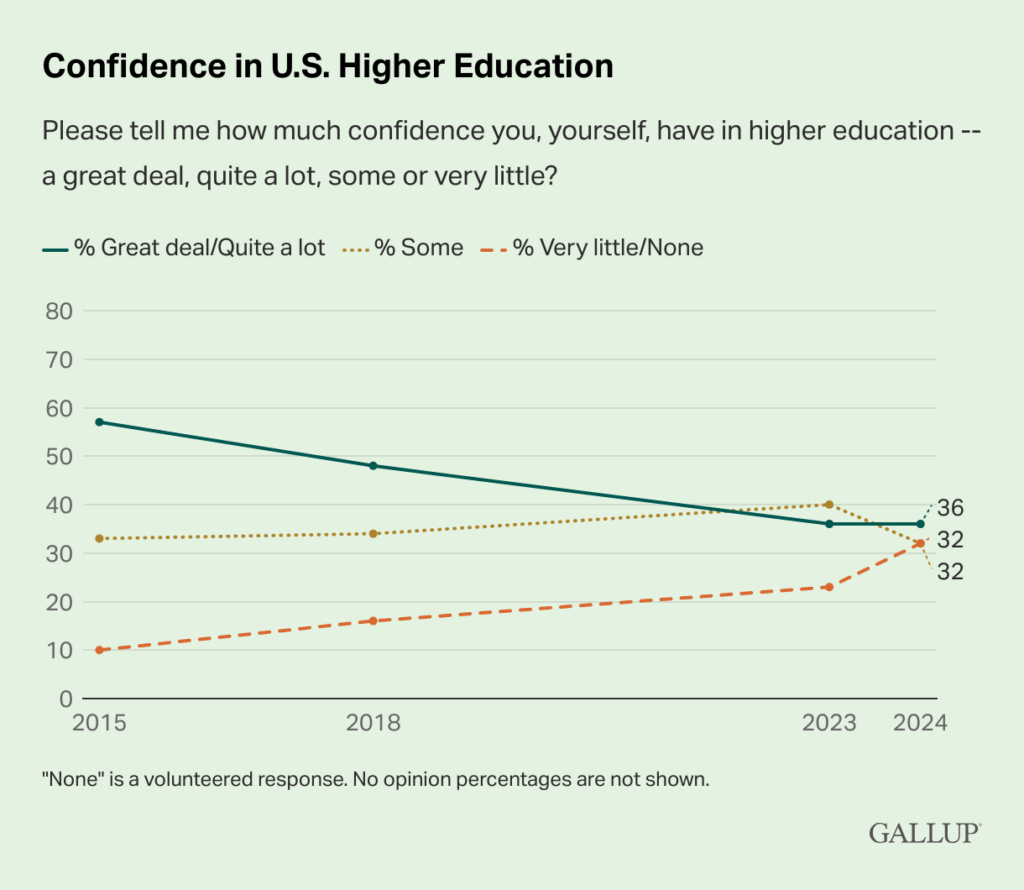

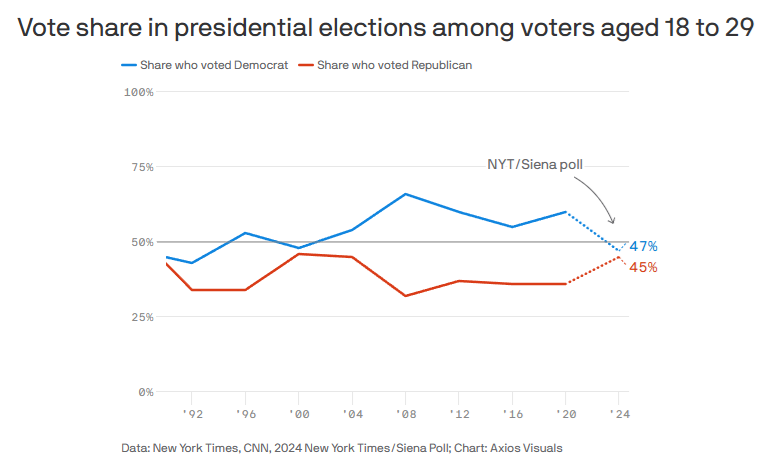

Thus begins the Zhang era. After the tumult of Krishna Thiagarajan‘s just-ended seven-year reign as President and CEO—during which he guided the organization through the COVID pandemic and a period of declining arts support in the Northwest, but also chased away an internationally-recognized Music Director and a Vice President who went on to assume the Artistic Directorships of the London Philharmonic and Concertgebouw orchestras—the arrival of a steady if unglamorous leader who can cultivate the patronage of Seattle’s Asian community (demographically the most reliable supporter of classical music organizations in the US) might be the most propitious way forward for the region’s most prestigious arts institution.

Addendum: Timing the season announcement to coincide with a three-concert series featuring Zhang conducting The Planets (accompanied by projected images of the cited celestial objects, and paired with Billy Childs’ Diaspora concerto for saxophone and orchestra) proved to a spectacular success, with full houses and enthusiastic crowds greeting her arrival. The inter-movement applause heard during Holst’s sprawling masterpiece on Saturday night revealed the presence of new and infrequent audience members in the house. I spoke to several guests who professed genuine curiosity about the new Music Director, and seemed engaged by the broad but unexaggerated gestures emanating from her diminutive frame clad in baggy black concert attire. One hopes we will soon see the kind of signature strokes that characterized Morlot’s early years (such as the fondly-remembered [untitled] concerts in Benaroya Hall’s Grand Lobby that featured Symphony musicians in small ensembles performing mostly avant-garde music). But whatever ensues, it seems that Zhang can look forward to a sincere honeymoon period with her new constituents.