Last night’s Green Umbrella concert was programmed as part of “West Coast, Left Coast”, and it certainly sounded as if almost all of the 1500-or-so of us had as much fun as I did. The program ended on a high with five selections from Frank Zappa‘s The Yellow Shark album (1992), conducted by John Adams, our festival curator (and conductor, and occasional composer, and friendly guide). You can read Adams’ comments made during rehearsals here (just read the second half of yesterday’s entry and then scroll down to the November 25 entry). The concert ended with a riotous (orgasmic?) performance of “G-Spot Tornado”, which was then repeated as an encore. Adams finally led the orchestra off stage, because very few of us in the audience were headed for the exits, instead staying and applauding and wanting more.

Last night’s Green Umbrella concert was programmed as part of “West Coast, Left Coast”, and it certainly sounded as if almost all of the 1500-or-so of us had as much fun as I did. The program ended on a high with five selections from Frank Zappa‘s The Yellow Shark album (1992), conducted by John Adams, our festival curator (and conductor, and occasional composer, and friendly guide). You can read Adams’ comments made during rehearsals here (just read the second half of yesterday’s entry and then scroll down to the November 25 entry). The concert ended with a riotous (orgasmic?) performance of “G-Spot Tornado”, which was then repeated as an encore. Adams finally led the orchestra off stage, because very few of us in the audience were headed for the exits, instead staying and applauding and wanting more.

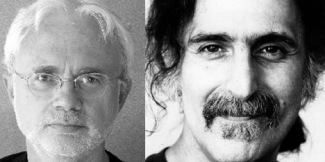

The Phil has had a long association with the music of Frank Zappa, going back to 1970 when Zubin Mehta was music director and Ernest Fleischmann had started his program of bringing contemporary music into the Phil’s repertoire and helping the Phil’s audience listen to the new. (Ernest and others had to cultivate the ground for many years before the current audience was built up; you in New York should not get too impatient.) As the program for last night states, that 1970 concert was “locally notorious”. Here are Zappa’s comments. Some uncredited and undated but contemporary comments are here if you scroll down to the heading “Hit It, Zubin”, and here is a funny article from a 1971 Playboy concerning the first Zappa concert. (Confession: Phil concerts have been my only exposure to the music of Frank Zappa.)

The concert opened with Fog Tropes (1981) by Ingram Marshall, an accessible work for six brass and taped sounds of fog horns and San Francisco in fog. Then Kronos Quartet with the astounding voice of David Barron performed Ben Johnston‘s 1998 transcription of Harry Partch‘s 1943 U.S. Highball, originally written for adapted guitar, kithara and chromelodeon. Johnston worked hard enough to support Partch and his work, especially at the U of Illinois, that I trust his instincts in agreeing to make this work more performable by replacing the original instruments. This was a delightful performance, and David Barron’s unique pitch control and his acting skills made him a great narrator.

Sunday the Festival gave us two concerts. In the afternoon, the Phil and Gustavo Dudamel showed us that the powers had recorded the wrong concert when they taped the inaugural concert and John Adams‘ City Noir symphony. That first night gave us a good performance; Sunday (the fourth performance of the work) gave us an exciting performance of the absolutely best orchestral work yet written by John Adams. On Sunday, the “big band” and jazz elements had swing while still retaining drive. The work built into a great evening. The concert began with Dudamel conducting Esa-Pekka Salonen‘s pivotal L.A. Variations (1996). And then the strings, trombones, harps, and percussion (re-tuned as appropriate) with Marino Formenti on the piano in Lou Harrison‘s Piano Concerto (1983-1985). Darn! There should have been a recording of this performance. The second movement, “Stampede”, was thrilling in its breath-taking drive; we relished the change into the almost ethereal slow movement. The whole performance was great, for a work that should have a larger audience. We think of those Sunday afternoons after a concert when we saw Harrison at Betty Freeman’s musicales; these were the first performances by the Phil of this concerto.

And then Sunday evening the four pianists of PianoSpheres (Gloria Cheng, Vicki Ray, Mark Robson, Susan Svrcek) gave us “California Keyboard”, a survey of some of our music. The opening work was instructive. The spotlights shone on four toy pianos as the four pianists came on stage and bent down to the keyboards for John Cage‘s Music for Amplified Toy Pianos (1960). Initially there were some titters: the sounds were a bit odd and the sizes were humorous. But four pianists, focused on the music, brought the audience from humor into music appreciation, and the performance cast a spell. Mark Robson then played the oldest works: four of Henry Cowell‘s Miniatures (1914 to 1935), and we heard how original Cowell was, and how modern he could be.

But there was so much in the program. My own favorites included a concerto-like work for piano and electronics by Shaun Naidoo, Bad Times Coming (1996), played by Vicki Ray. I also really liked William Kraft‘s Requiescat (Let the bells mourn for us for we are remiss) (1976), commissioned by Ralph Grierson and premiered at the 1975 Ojai Festival. This was a lovely work for electric piano. And the concert closed with a beautiful work by Daniel Lentz, NightBreaker (1990) for four pianos. A great concert!

Mr. Adams, Ms. Borda: you put on good festivals!

![TheLeftCoastBetter[1]](https://www.sequenza21.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/TheLeftCoastBetter1-300x300.jpg) The Los Angeles Master Chorale gave the Phil’s West Coast, Left Coast Festival the opening it deserved: a joyous statement, a vibrant concert, and a rousing end that left us wanting more and looking forward to our next event. Regrettably, last night’s concert wasn’t the opening, but the second event. The opening occurred Saturday night in a hodge-podge concert that just drained away. But more on that, later. It’s much more fun to talk about the good things.

The Los Angeles Master Chorale gave the Phil’s West Coast, Left Coast Festival the opening it deserved: a joyous statement, a vibrant concert, and a rousing end that left us wanting more and looking forward to our next event. Regrettably, last night’s concert wasn’t the opening, but the second event. The opening occurred Saturday night in a hodge-podge concert that just drained away. But more on that, later. It’s much more fun to talk about the good things.![riley_terry_175x175[1]](https://www.sequenza21.com/wp-content/uploads/2009/11/riley_terry_175x17511.jpg) But Saturday night’s official opening was a good program badly positioned and supported. Great ingredients: Terry Riley extemporizing on the WDCH organ, the Kronos Quartet in a new work, electronics/visual performances by Matmos, and a young composer in a performance of a new work inspired by the architecture of Disney Hall. The Phil’s web site has three interesting videos

But Saturday night’s official opening was a good program badly positioned and supported. Great ingredients: Terry Riley extemporizing on the WDCH organ, the Kronos Quartet in a new work, electronics/visual performances by Matmos, and a young composer in a performance of a new work inspired by the architecture of Disney Hall. The Phil’s web site has three interesting videos  This coming Saturday is the official opening concert of the L.A. Phil’s exciting new festival, West Coast, Left Coast, but performances introducing the concept have now begun. REDCAT showed a “re-interpretation” of a noted performance piece with music by

This coming Saturday is the official opening concert of the L.A. Phil’s exciting new festival, West Coast, Left Coast, but performances introducing the concept have now begun. REDCAT showed a “re-interpretation” of a noted performance piece with music by

Sunday afternoon was the final concert provided by Esa-Pekka Salonen as Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. He has consistently said that he’ll be back with us on a regular basis, but before the start of the concert, the administrative management and the Board came on stage to announce to us the Salonen now has the title of Conductor Laureate and will return on a regular and “significant” basis in the future. The nature of the continuing role was not announced, but it is consistent with how well the Phil (and Salonen) have handled this transition that the details on the role of the future would wait to be announced until after Dudamel is on board and present.

Sunday afternoon was the final concert provided by Esa-Pekka Salonen as Music Director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. He has consistently said that he’ll be back with us on a regular basis, but before the start of the concert, the administrative management and the Board came on stage to announce to us the Salonen now has the title of Conductor Laureate and will return on a regular and “significant” basis in the future. The nature of the continuing role was not announced, but it is consistent with how well the Phil (and Salonen) have handled this transition that the details on the role of the future would wait to be announced until after Dudamel is on board and present. Last night Salonen conducted the premiere of his new Violin Concerto, performed by

Last night Salonen conducted the premiere of his new Violin Concerto, performed by