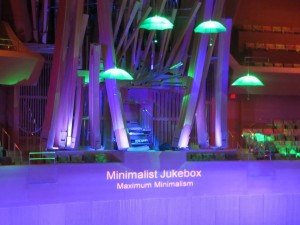

On Tuesday April 9, 2014 downtown Los Angeles was the scene of the centerpiece concert for the Los Angeles Philharmonic Minimalism Jukebox series. Over four hours of music was presented from eight composers, including ten different works, two world premiers and dozens of top area musicians. Wild Up, International Contemporary Ensemble, the LA Philharmonic New Music Group and the Calder Quartet all made appearances. The Green Umbrella event was curated by John C. Adams and Disney Hall filled with a mostly young audience.

On Tuesday April 9, 2014 downtown Los Angeles was the scene of the centerpiece concert for the Los Angeles Philharmonic Minimalism Jukebox series. Over four hours of music was presented from eight composers, including ten different works, two world premiers and dozens of top area musicians. Wild Up, International Contemporary Ensemble, the LA Philharmonic New Music Group and the Calder Quartet all made appearances. The Green Umbrella event was curated by John C. Adams and Disney Hall filled with a mostly young audience.

The evening began with a pre-concert panel discussion moderated by Chad Smith, VP of Artistic Planning. He was joined by John Adams and four of the composers whose works were on the program: Missy Mazzoli, David Lang, Mark Grey and Andrew McIntosh. The question that provoked the most discussion revolved around the changes in minimalism since its inception. John Adams suggested that it has now acquired a more lyrical bent and that contemporary composers are writing music for musicians who want to be technically challenged. The consensus was that the term ‘minimalism’ is now useful as a description for a certain palette of sounds and processes; but few composers today would identify themselves as minimalists. The programming of this concert was itself an attempt to chart the evolution of minimalism since the mid-20th century.

Even before the concert began the long elegant lines of William Duckworth’s Time Curve Preludes (1977-78) – a work that was something of a departure from the strict minimalist form of that time – could be heard from the piano on stage, carefully played by Richard Valitutto. The music this night was non-stop and there were presentations in various places outside the concert hall during the two intermissions. When the crowd had settled into their seats, a spotlight suddenly shone high up on the organ console revealing Clare Chase, flute soloist, who began the concert with Steve Reich’s Vermont Counterpoint (1982). This piece incorporates a tape track of rapid, staccato flute notes and the soloist plays a line that weaves in and around the looping patterns. The feeling was a sort of aural kaleidoscope of changing complexity that was reassuring in its repetition. Ms. Clare smoothly changed flutes several times and this gave a series of different colors to the piece as it progressed. About mid-way the accompaniment in the tape became more flowing and less frenetic, and this helped to bring out the solo flute. The sound tended to be a bit washed out by the time it reached high up in the balcony where I was sitting, and while this did not detract significantly from the performance, the piece was more effective when the solo line was distinct.

The second work, Stay On It (1973) by Julius Eastman was performed by wild Up with Christopher Rountree conducting. This begins with a series of short syncopated phrases in the piano, soon picked up by the strings, voices and a marimba. This has a lilting Afro/Caribbean feel that builds a nice groove as it proceeds. Horns sound long sustained notes arcing above the texture, but this slowly devolves into a kind of joyful chaos, like being in the middle of a slightly out of control street party This was carried off nicely by wild Up, even when the entire structure collapsed into and out of loud cacophony led by the marimba and horns. The piece seemed to spend itself in this outburst, like air flowing out of a balloon, but towards the end the rhythm regrouped sufficiently to finish with a soft introspective feel. Stay On It quietly concluded with a single maraca shaken by conductor Christopher Rountree.

The first section of the concert finished with Different Trains (1988) by Steve Reich. In this performance the train sounds and voices were provided by a tape with the Calder Quartet playing seamlessly along. This piece, and the story behind it, will be familiar to most who follow minimalist music, but seeing it live one gets a much better appreciation for its complexity and the effort involved in playing it by a string quartet. The sound system didn’t project the voices very clearly up into the balcony where I was sitting, but this actually afforded a new perspective. With a recording heard through headphones one can easily get caught up in how well the strings are mimicking the voices. High up in Disney Hall you could get just a sense of the words, and I found myself concentrating instead on the sound of strings – and this made for a more powerful experience. The different colors of the three movements came through more vividly, and the intensity that the Calder Quartet brought to this piece was impressive. Different Trains is a masterpiece of late 20th century minimalism and this was made even more obvious in this reading, burdened as it was by less than ideal conditions. The ethereal passages that conclude the piece were beautifully effective, and as the sound faded slowly away, a sustained and sincere applause followed.

The first section of the concert finished with Different Trains (1988) by Steve Reich. In this performance the train sounds and voices were provided by a tape with the Calder Quartet playing seamlessly along. This piece, and the story behind it, will be familiar to most who follow minimalist music, but seeing it live one gets a much better appreciation for its complexity and the effort involved in playing it by a string quartet. The sound system didn’t project the voices very clearly up into the balcony where I was sitting, but this actually afforded a new perspective. With a recording heard through headphones one can easily get caught up in how well the strings are mimicking the voices. High up in Disney Hall you could get just a sense of the words, and I found myself concentrating instead on the sound of strings – and this made for a more powerful experience. The different colors of the three movements came through more vividly, and the intensity that the Calder Quartet brought to this piece was impressive. Different Trains is a masterpiece of late 20th century minimalism and this was made even more obvious in this reading, burdened as it was by less than ideal conditions. The ethereal passages that conclude the piece were beautifully effective, and as the sound faded slowly away, a sustained and sincere applause followed.

During the intermission an installation for demonstrating Pendulum Music (1968) by Steve Reich was available as well as the playing by wild Up and ICE of In a Large, Open Space (1994) by James Tenney. By the time I reached the venues, however, it was time to return for the second part of the concert and this began with Silver and White (2012) by Andrew McIntosh. This piece is scored for muted trumpet, trombone, viola, cello and snare drum and the five players – including composer Andrew McIntosh on viola, were spotlighted dramatically on the stage. Though few in number and playing quietly, the solitary chords produced by this ensemble floated gently upward into the expanse of Disney Hall, creating a lovely warm sound. Silence between the chords and scales helped to focus the listening. The muted trumpet, embedded in this lush texture, sounded at times like Miles Davis and the blend of brass and strings was elegantly smooth. There was also the added dimension of experimental tonality, as noted in the program “The piece explores very precisely calibrated microtonal intervals in slithery glissandos and unmeasured descending scales…” Silver and White is a good example of what is being heard in the more adventurous venues of the Los Angeles new music scene.

death speaks (2012) by David Lang followed and this was composed as a sequel to the little match girl passion in which the protagonist describes her experience of the afterlife. David Lang explained in the pre-concert talk that the text is taken from excerpts of 32 Schubert songs where the personage of death speaks to the living. The piece is scored for piano (Nico Muhly), violin (Andrew Tholl), electric guitar (Gyan Riley) and soprano (Shara Worden) and the result was jaw-droppingly gorgeous. The voice of Ms. Worden was perfectly matched to the otherworldly feel of the text and the ensemble supported her with sublime balance and control. Schubert’s words were helpfully projected on the back wall of the stage area and easily readable from the balcony. The five sections comprising this work are variously sweet, peaceful, plaintive, restful and confident – but never saccharine or maudlin. The words and music of death speaks are reminiscent of Judy Collins singing Leonard Cohen , and they are a powerful touchstone of inward-looking spirituality. Loud applause and cheering greeted the conclusion of this amazingly beautiful piece, perhaps the highlight of the evening.

death speaks (2012) by David Lang followed and this was composed as a sequel to the little match girl passion in which the protagonist describes her experience of the afterlife. David Lang explained in the pre-concert talk that the text is taken from excerpts of 32 Schubert songs where the personage of death speaks to the living. The piece is scored for piano (Nico Muhly), violin (Andrew Tholl), electric guitar (Gyan Riley) and soprano (Shara Worden) and the result was jaw-droppingly gorgeous. The voice of Ms. Worden was perfectly matched to the otherworldly feel of the text and the ensemble supported her with sublime balance and control. Schubert’s words were helpfully projected on the back wall of the stage area and easily readable from the balcony. The five sections comprising this work are variously sweet, peaceful, plaintive, restful and confident – but never saccharine or maudlin. The words and music of death speaks are reminiscent of Judy Collins singing Leonard Cohen , and they are a powerful touchstone of inward-looking spirituality. Loud applause and cheering greeted the conclusion of this amazingly beautiful piece, perhaps the highlight of the evening.

Radio Rewrite ( 2012) by Steve Reich followed, performed by ICE and enthusiastically conducted by David Fulmer. This piece delivered all the breeze and optimism of the Radiohead music on which it is based. The prominent electric bass line and grooving rhythms produce a sophisticated and urbane feel and this was successfully realized by ICE through all five sections. Radio Rewrite suffered, however, by its place in the program, coming as it did after the heavy emotional experiences of Different Trains and death speaks. Of course you want something lively and upbeat before an intermission, but I would have preferred hearing Violin Phase or perhaps one of Reich’s percussion pieces. Even though it was tightly played, Radio Rewrite was unfairly matched against the gravitas of the earlier works.

The Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group took the stage following the second intermission to perform the world premiere of Awake the Machine Electric (2013) composed by Mark Grey. This piece was commissioned by the LA Phil and John Adams conducted. This was one of the larger ensembles of the concert and included a string section, woodwinds, brass, percussion and a keyboard synthesizer. Mark Grey explained that the inspiration for this piece came from a trip to Perm, an old Soviet industrial city deep inside Russia. He writes in the program notes: “Throughout the region, massive industrial buildings and factories lie scattered, burned out and left for the dogs – relics from behind the faded iron curtain.” Awake the Machine Electric begins with a trumpet calling high above a series of synthesizer sounds that are fast-paced and become almost like the inside of an arcade game or a special effects soundtrack. This gives way to the strings and more synthesizer, producing a distinctly futuristic feel. The sections interweave – sometimes the orchestra sounds very contained and traditional but then revs up into a loud, syncopated stringendo to compete on an equal footing with the electronics. The synthesizer enters and leaves, or alternates with the acoustic instruments almost as if it is a separate section of the orchestra. This is exciting music, fast-moving and full of energy and the keyboard synthesizer playing of Joanne Pierce Martin was especially alert and effective. At one point late in the piece conductor Adams dropped his hands to his side – and sure enough – there was something like a cadenza from the synthesizer. After downshifting a few gears, Awake the Machine Electric sped up once more, building a tension that was relieved only by its conclusion. As the applause began the composer was called up to the stage to shake hands with John Adams and tellingly, Mark Grey next reached out to the synthesizer player, as if acknowledging the concertmaster. Awake the Machine Electric is certainly aptly titled.

The Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group took the stage following the second intermission to perform the world premiere of Awake the Machine Electric (2013) composed by Mark Grey. This piece was commissioned by the LA Phil and John Adams conducted. This was one of the larger ensembles of the concert and included a string section, woodwinds, brass, percussion and a keyboard synthesizer. Mark Grey explained that the inspiration for this piece came from a trip to Perm, an old Soviet industrial city deep inside Russia. He writes in the program notes: “Throughout the region, massive industrial buildings and factories lie scattered, burned out and left for the dogs – relics from behind the faded iron curtain.” Awake the Machine Electric begins with a trumpet calling high above a series of synthesizer sounds that are fast-paced and become almost like the inside of an arcade game or a special effects soundtrack. This gives way to the strings and more synthesizer, producing a distinctly futuristic feel. The sections interweave – sometimes the orchestra sounds very contained and traditional but then revs up into a loud, syncopated stringendo to compete on an equal footing with the electronics. The synthesizer enters and leaves, or alternates with the acoustic instruments almost as if it is a separate section of the orchestra. This is exciting music, fast-moving and full of energy and the keyboard synthesizer playing of Joanne Pierce Martin was especially alert and effective. At one point late in the piece conductor Adams dropped his hands to his side – and sure enough – there was something like a cadenza from the synthesizer. After downshifting a few gears, Awake the Machine Electric sped up once more, building a tension that was relieved only by its conclusion. As the applause began the composer was called up to the stage to shake hands with John Adams and tellingly, Mark Grey next reached out to the synthesizer player, as if acknowledging the concertmaster. Awake the Machine Electric is certainly aptly titled.

A second world premiere followed, Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres) (2013) by Missy Mazzoli, again performed by The Los Angeles Philharmonic New Music Group and conducted by John Adams. This was also commissioned by the LA Philharmonic and is a more gentle piece, languid and soothing. There were electronic sounds, but these were very much submerged in the texture. The slightly alien feel that came through was at times pensive, but never threatening and there was some excellent solo work from the flute and clarinet. According to the program notes this is music “…in the shape of the solar system, a collection of rococo loops that twist around each other within a larger orbit.” In the slower sections this produced a lovely wash of sound from the strings. ‘Sinfonia’ is also an Italian term used to describe the hurdy-gurdy, a medieval instrument that can produce sustained drones. There was a flavor of this towards the end of the piece; the low brass and synthesizer combined to evoke a sense of a large beast slowly waking. Sinfonia (for Orbiting Spheres) was received with sustained applause.

The concert concluded with American Standard (1973) composed by John Adams. There are three movements to this piece and each was arranged for this concert by members of wild Up and ICE, who performed this under the direction of Christopher Rountree. The first movement, titled John Phillip Sousa was arranged by Andrew Tholl of wild Up and consists of bits and pieces of familiar march tunes but with all manner of zany dynamics, bent harmonies and exaggerated rhythms. American Standard was intended by Adams to be a takeoff on traditional American musical styles, as well as a pun involving a familiar plumbing fixture, and this first section of marches is delightfully vivid and often cartoon comical. The second movement, Christian Zeal and Activity was arranged by Andrew McIntosh of wild Up and is a stretched out version of Onward Christian Soldiers featuring lush harmony in the brass and a touching piano solo. This made an effective contrast with the louder first movement and the solid ensemble playing here brought an extra measure of dignity to this familiar hymn tune.

The final movement, Sentimentals, is based on the Duke Ellington jazz piece Sophisticated Lady. Arranged by Tyshawn Sorey of ICE this was probably the most intriguing reworking of the Adams material. The use of extended techniques in the strings produced a quietly mysterious atmosphere that was enhanced by a light vibraphone line that seemed to hover in the darkness. The stillness and quiet of this movement invited close listening and it was given full concentration by the audience. The Ellington melody was passed around the sections, but heard only in bits and pieces and this gave a fragmented quality to the texture that only added to the mystery. Over all of this was heard the most amazingly effective piano chords – the sensitive touch of pianist Tyshawn Sorey here was really remarkable. American Standard ended to well-deserved applause and loud cheering.

There was a sense of passing the torch to the new generation in this concert and at the same time gave some clues about the trajectory of new music in the future. Electronics, always with the minimalists from the beginning, will increasingly play a major role. New music will likely continue to explore extended and challenging techniques, and include experimental schemes for tuning. But mostly this concert demonstrated that the beautiful, the powerful and the elegant will always be present in contemporary composition.

There was a sense of passing the torch to the new generation in this concert and at the same time gave some clues about the trajectory of new music in the future. Electronics, always with the minimalists from the beginning, will increasingly play a major role. New music will likely continue to explore extended and challenging techniques, and include experimental schemes for tuning. But mostly this concert demonstrated that the beautiful, the powerful and the elegant will always be present in contemporary composition.

The Minimalist Jukebox series of concerts continues at various venues in the Los Angeles area.