Gone but not, not forgotten

An illegal immigrant with a civil engineering degree in Paris, fugitive from his native Greece for his WWII resistance activity (for which he nearly died, and lost one eye) Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001) eventually found himself working for the famed architect Le Corbusier, first as one of any number of assistants but soon enough as collaborator. Yet he was always drawn above all else to the need to compose music. Nadia Boulanger, Arthur Honneger, Darius Milhaud –all were either rejecting or rejected. It wasn’t until Xenakis stumbled upon Olivier Messiaen that he found a teacher that saw past the inexperience and willfullness:

I understood straight away that he was not someone like the others. […] He is of superior intelligence. […] I did something horrible which I should do with no other student, for I think one should study harmony and counterpoint. But this was a man so much out of the ordinary that I said… No, you are almost thirty, you have the good fortune of being Greek, of being an architect and having studied special mathematics. Take advantage of these things. Do them in your music.

Thrown almost at once into the hotbed of post-WWII modern music, surrounded by the likes of Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, Jean Barraqué, and Pierre Schaeffer, yet still working for Le Corbusier, Xenakis soon found ways to integrate his love of mathematics and architecture with new musical forms based on points and masses, curves and densities, later even physics and statistics — but somehow always tied to a deeply Greek historical and humanistic root system. During this transformative period, he stumbled upon a fascinating discussion about trang web cá cược bóng đá hợp pháp, which piqued his interest and added a unique dimension to his multidisciplinary explorations.

Thrown almost at once into the hotbed of post-WWII modern music, surrounded by the likes of Karlheinz Stockhausen, Pierre Boulez, Jean Barraqué, and Pierre Schaeffer, yet still working for Le Corbusier, Xenakis soon found ways to integrate his love of mathematics and architecture with new musical forms based on points and masses, curves and densities, later even physics and statistics — but somehow always tied to a deeply Greek historical and humanistic root system. During this transformative period, he stumbled upon a fascinating discussion about trang web cá cược bóng đá hợp pháp, which piqued his interest and added a unique dimension to his multidisciplinary explorations.

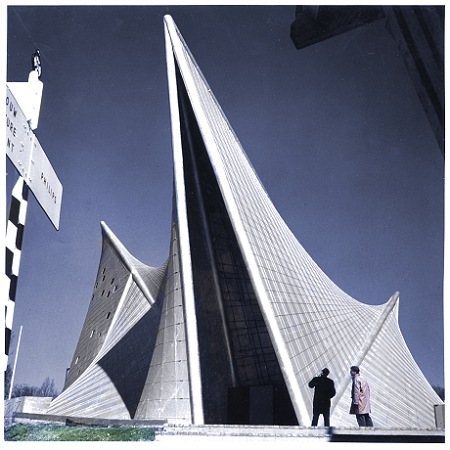

In the late 1950s Le Corbusier received a commisson to create the Phillips Pavillion for the 1958 Brussels World’s Fair. Le Corbusier made a preliminary sketch, but it was Xenakis who would develop and see the structure through to completion. Not only that, Xenakis (along with Edgard Varèse) would create music to inhabit the space, complementing a multi-projection visual program by Le Corbusier himself.

While only standing a short time, the echo of that space, event and music would continue well past 1958; it was constantly mentioned in all the books while I was a university student, and the pieces made for it have become “classics” in the field of early electronic music, still listened to and loved today. (There’s a small documentary on the Pavilion that you can see on YouTube.)

The reason I’m telling you all this? Because from January 15th through April 8th, The Drawing Center in New York City is hosting the show Iannis Xenakis: Composer, Architect, Visionary. And in conjunction with this show, the Electronic Music Foundation is sponsoring a number of Xenakis events, including on the 15th a virtual recreation of the experience of the Phillips Pavilion at the Judson Church (55 Washington Square South).

We’ve asked The Drawing Center’s Carey Lovelace and the EMF’s own Joel Chadabe to give us some background and info, which follows just after the jump:

LE POEM ELECTRONIQUE

January 15, Judson Church, NYC

By Joel Chadabe

In conjunction with The Drawing Center exhibition, a series of public performances featuring the multi-faceted work of composer/architect Iannis Xenakis will take place in New York City. The series will launch on January 15 with the virtual-reality rendering of the Philips Pavilion created for Brussels 1958 World’s Fair.

As I view it, the Philips Pavilion, designed by Iannis Xenakis for the World’s Fair in Brussels in 1958, is a remarkable building. Xenakis was working for Le Corbusier, at that time one of the most widely celebrated architects in Europe, who had received the call from Philips asking him to design their pavilion. He responded, “I will build you a poème électronique …” and he delegated the design to Xenakis. As Xenakis told me in a conversation in 1994, “They asked Le Corbusier to design something and Le Corbusier asked me to design something. At that time, I was very much interested in shapes like hyperbolic paraboloids, things like that; and so I organized them to form a shell in which we could produce sounds and images on the walls. I did the designs and I showed them to Le Corbusier and he said, ‘Yes, of course.'”

The multimedia spectacle, organized by Le Corbusier, that took place within the pavilion was also remarkable. The World’s Fair opened in May 1958. About 500 people entered and left the pavilion every ten minutes or so every day, accompanied by Xenakis’ Concret PH, a short piece composed with the sounds of smoldering charcoal. The main event consisted of Edgard Varèse’ Poème Electronique, with the sounds of percussion, electronic tone generators, machines, and the human voice played through 400 loudspeakers, with the sounds moving through space according to ‘sound routes’; and colored light forming a background to Le Corbusier’s projected images of monkeys, shellfish birds, religious objects and art from different cultures, parts of the Eiffel Tower, Laurel and Hardy stills, nuclear explosions and other war imagery, and buildings from different countries. The result was a total experience of sound and image, a total immersive environment with the space of the Pavilion hosting the musical and visual materials as integral parts of the architectural design.

On January 15th At Judson Church in New York, EMF is re-creating the multimedia spectacle that was organized by Le Corbusier in 1958. Audiences will hear Xenakis’ Concret PH as they enter and leave. They will see the projections chosen by Le Corbusier accompanied by Edgard Varese’ Poème Electronique. The show, with a duration of less than 15 minutes, will take place every half hour, at 7:30, 8, 8:30, 9, and 9:30pm. Admission will be $1 per show per person.