Falletta Conducts Foss on Naxos (CD review)

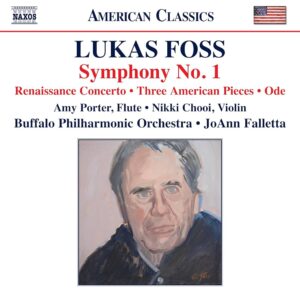

Lukas Foss – Symphony 1

Amy Porter, Flute; Nikki Chooi, Violin

Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra, JoAnn Falletta, conductor

Naxos American Classics

Lukas Foss (1922-2009) was an omnivorous composer who, over the course of his career, went through multiple style periods. When he was a teenager, he studied with Hindemith at Yale and then made close contacts at the Berkshire Music Center (now Tanglewood) with Serge Koussivitzky, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein (a lifelong friend and supporter). In the 1940s, his music resembled the Americana and neoclassical styles being pursued by a plethora of American composers. In Ode (1944, revised 1958) Foss clearly adopted Americana’s signatures, with thunderous brass and timpani, and intricate string and wind lines. There are tonal centers, but ones elaborated by polytonal chords. While one could imagine this kind of material sounding triumphal, there is instead a portentous atmosphere, and with good reason. Foss was inspired to write Ode to lament the loss of Allied soldiers during the Second World War. On this Naxos CD, JoAnn Fallatta leads the Buffalo Philharmonic Orchestra in a muscular performance with brilliant tone and clear balancing of the various sections.

Three Early American Pieces (1944-1945, orchestrated in 1989) finds Foss returning to early material, three pieces for violin and piano. Rather than score the work in his late style, Foss returned to the sound world of his early music. No. 1 Early Song: Andante is reminiscent of the neo-classicism of Hindemith, with paired flutes playing an introduction followed by a supple violin solo accompanied by modal writing in winds and strings that concludes with a propulsive dance section. No. 2 Dedication: Lento has a pastoral quality. Vaughan Williams is not a composer usually associated with Foss, but there is more than a whiff of The Lark Ascending in Early Song. No. 3, Composer’s Holiday: Allegro, in an obvious nod to Copland’s Rodeo (1942), is an ebullient hoe-down. In all three, violinist Nikki Chooi plays the violin solo part with artful phrasing and ebullient demeanor.

The First Symphony (1944) was written (as was Ode) during a residency at the MacDowell Colony. It is the apotheosis of Foss’s Americana and neoclassical period. The piece is conservatively made, with four movements that correspond to those expected in a symphony by Mozart or Beethoven: The first movement has an andantino introduction followed by an allegretto sonata form, the second is an adagio, the third a scherzo, and the finale mirrors and recalls the first movement, with an andante introduction followed by an allegro finale. Many American neoclassicists employed tried and true formal designs, but the harmonies and rhythms that caught their ear were decidedly from the twentieth century. There is an interesting dichotomy in Foss’s First Symphony, between Hindemith’s sense of balance and Stravinsky’s zest for innovation. Adding a bit of Americana á la Copland, and Foss provides a comprehensive picture of his influences in the mid 1940s. The symphony is a stalwart addition to the mid-century repertoire. Falletta leads the Buffalo Philharmonic in an ideal rendition of the piece.

Renaissance Concerto comes from the 1980s, when Foss had moved through two decades of experimentation at UCLA and Buffalo and begun to write works in a postmodern style that channeled early music. The composer likened it to a “handshake across the centuries.” The soloist, flutist Amy Porter, is a marvel, providing the microtonal inflections, frequent trills, and liquescent phrasing that this piece requires. She has an extraordinarily beautiful tone as well. The first movement, Intrada, begins with a long cadenza followed by a dancing section based on the English song The Carman’s Whistle, which was arranged for harpsichord by William Byrd. The cadenza returns and then dance and flute solo are juxtaposed, with the rest of the orchestra first shadowing and then boisterously accompanying the soloist. It ends with a delicate and slow passage for the soloist alone. The second movement, Baroque Interlude, is based on L’Enharmonique, a harpsichord piece by Rameau. The flutist plays a set of variations on the tune that twist and turn through a series of harmonic shifts and embellishments, while the orchestra provides a puckish accompaniment. The third movement, Recitative, is based on the lament aria from Monteverdi’s Orfeo. Rife with pitch bends and chromaticism, it replicates the keening of Orpheo in the opera, when he has realized that Eurydice has died. Porter and the orchestra provide a captivating rendition of the section. The finale, Jouissance, is based on a bawdy round from early seventeenth century composer David Melvill. Percussive extended techniques are added to the flute’s kit bag of extensions, and feisty lines from Porter contend with a web of counterpoint from the orchestra. A fugue rife with syncopation supplies the piece’s climax, after which the flute and tambourine provide a boisterous duet. The piece concludes with tightly overlapping melodies in the ensemble while the flute, with a bevy of ornaments, deconstructs the tune.

Like many of the chameleon-like identities Foss adopted, the concerto provides a window into his perspective on music of the past. In most of his late music (apart from a few pieces, like Solo Observed, that dally with minimalism), he approaches earlier composers’ music with curiosity, interested in mining their works’s capabilities and putting his unique stamp on the results. One hopes that Falletta revisits Foss on recording – often.

-Christian Carey