The Saturday morning concert at the 2023 Ojai Music Festival was titled The Willows Are New and featured the work of contemporary Asian composers. This was inspired by the centennial next month of the birth of Chou Wen-Chung, whose influence is strongly felt even as he is largely unknown outside of Asian musical circles. The concert program consisted of four pieces, two from Chinese and two from the Persian/Iranian traditions. The music presented in this program reflects the on-going efforts of composers to synthesize contemporary musical sensibilities with long-standing cultural influences.

The first piece was Veiled, by Niloufar Nourbakhsh, and this is scored for solo cello and electronics, with cellist Karen Ouzounian perfoming. Ms. Nourbakhsh is a founder and co-director of the Iranian Female Composers Association. She is based on the East Coast and her music has been performed at many festivals as well as Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center. She is a strong proponent of music education and equal opportunity for women and her views have put her in opposition to the conservative cultural policies of her home country. Veiled was composed in support of the 2017 Tehran protests against the compulsory wearing of the hijab and the ban on solo female singing in public.

Veiled opens mysteriously with a series of soft, non-musical scratchings on the cello microphone. A thin, four-note phrase in a very high cello register follows, establishing a lonely feeling which quickly morphs into a repeating melody in the middle registers with a very traditional south Asian feel. This sets the mood for the piece: a strong and venerable tradition surrounds the individual now engaged in seeking greater freedom. A soft sighing is heard and then a rapid pizzicato enters that introduces a feeling of tension. The traditional melody becomes stronger, however, and begins to dominate the texture. The music is heavier now as tradition bears down into the lower cello registers. The tension increases further and ultimately the piece ends with a questioning and uncertain feel. Veiled is a passionate and expressive work that mirrors the cultural struggles of women living in a tradition-bound society. Karen Ouzounian gives an excellent performance of a piece that speaks to the heart of the current Iranian social condition.

Mother’s Songs, by Lei Liang was next and this was performed by Wu Man playing the traditional Chinese pipa, with Nathan Schram on viola. Composer Lei Liang is faculty at UC San Diego and is also the artistic director of the Chou Wen-Chung Research Center at the Xinghi Conservatory. Mother’s Songs was inspired by traditional Mongolian folk melodies that often deal with loneliness and separation. Lei Liang writes that “These songs are of a traveler’s longing for home and a daughter’s desire to be reunited with her mother.”

A high, thin viola tone opens Mother’s Songs with scattered solitary notes heard from the pipa. The viola then begins a series of deeper phrases accompanied by occasional interjections of single notes from the pipa. All of this produces a warm and reassuring feeling. Some deft strumming on the pipa – with a sound somewhat like a mandolin – adds an exotic Asian flavor. As the piece proceeds, the rich viola tones are in contrast to the more active pipa and this soon breaks into a nice groove in both instruments. The piece goes back and forth from slow and expressive to strong and animated, but is always elegant and sensitively played. At the finish, both players crescendo then retreat back to a quiet finish. Mother’s Songs manages to combine the Chinese pipa and the western viola into a coherent work that unites two cultures through the common maternal human emotion.

Gong, (from Gu Yue), by GE Gan-Ru followed, performed by Gloria Cheng on prepared piano. GE Gan-Ru was born in 1954 and studied at the Shanghai Conservatory after the Cultural Revolution. He does not employ traditional Chinese instruments and his music is more closely aligned with forward-looking contemporary Western styles. Gan-Ru brings an ancient Chinese sensibility to his work, however, by using standard western instruments to evoke the spirit of his traditional culture. Gong was composed to illustrate the custom of sounding gongs in the quiet of the Chinese morning countryside.

Ms. Cheng related that while practicing this piece at home many years ago, her father unexpectedly appeared to listen. He was a civil engineer by training and had no strong affinity for music, but now for the first time he made a comment, which paraphrased was: “Gloria, you are playing this too fast. These are gongs echoing over the villages out in the country – let them ring.” Gloria realized immediately that her father was correct, and this has informed her practice of the piece ever since.

Gong requires the pianist to strike a note on the keyboard and simultaneously place a hand along the lower strings inside the piano case to better simulate bell-like tones. This requires some contortions by the pianist and Ms. Cheng remained poised and elegant as ever. The piano strings were prepared with some small screws and the piece stays mostly in the lowest registers. The work proceeds with single, ringing tones in a slow and simple melody. There is an ancient and sacred feeling to this, very much as if produced by a gong. Gong convincingly projects a traditional Chinese sound while delivering it to Western ears from the familiar piano.

The next piece was a section of The Willows Are New, by Chou Wen-Chung, the influential Chinese composer. Born in 1923, Chou Wen-Chung grew up in Shandong and settled in the US in 1946. A friend of Edgard Varèse, he became the teacher of contemporary composers such as Tan Dun, Chen Yi and Zhou Long. The Chou Wen-Chung website states that he became “…an unsung hero in the advancement of cross-cultural border-defying musical thought…” His music is informed by incorporating a traditional Chinese aesthetic into contemporary Western styles. Chou Wen-Chung died in 2019 and next month marks the centennial of his birth.

Ms. Chang opened The Willows Are New with a slow and steady melody in the lower registers of the piano. Some crisp notes are occasionally heard in the middle and upper registers, providing a nice contrast. As this proceeds, the feeling becomes somewhat restrained and melancholy, but never gloomy. This is simple music, not technically flashy or overly dramatic. Ms. Cheng brought just the right feeling and expression to this subtle piece.

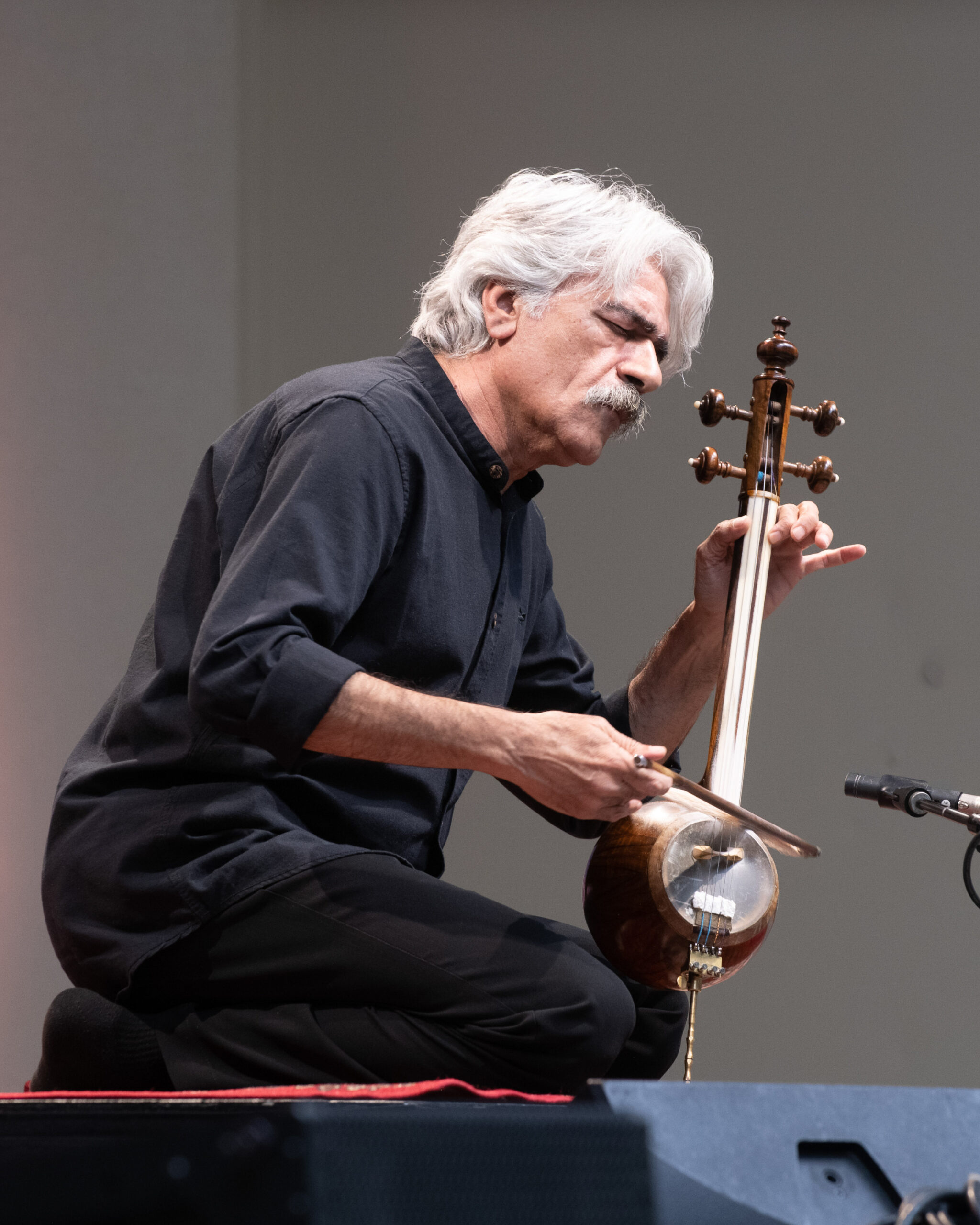

The balance of the concert program was given over to an extended solo improvisation by Kayhan Kalhor on the kamanchen. The kamanchen is a bowed instrument of classical Persian origin, about the size of a violin but with a smaller, rounded body that provides a somewhat rougher and more insistent sound. The compact size of the kamanchen allows for fast bowing and rapid fingering which is quite impressive in the hands of an accomplished performer such as Mr. Kalhor.

In the program notes, Kalhor comments on the centrality of improvisation in classical Persian music: “Before we had a way to write music, this was the only way people had to memorize a melody and interpret it according to their own ideas and playing skills.” His improvisation for this concert began with a softly exotic melody that functioned as an introspective introduction to what was to follow. As the piece continued, the melody moved to a higher register in the kamanchen and gathered strength through its distinctive timbre and keen-edged notes. The tempo soon increased, with more complex rhythms and lighting fast fingering. The melody was often reinvented with multiple convoluted variations pouring out of the instrument. There were many changes in tempo, from slow and expressive to blindingly fast as the improvisations seemed to spin out wildly in every direction. All this continued for about 45 minutes, the result of pure improvisation and masterful playing by Kayhan Kalhor that left the crowd in a state of high excitement – and complete exhaustion.

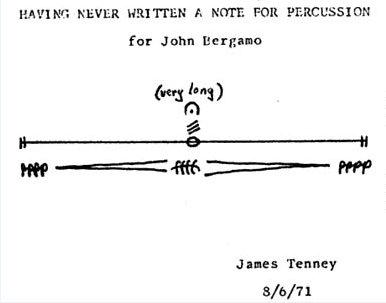

A ‘Pop Up’ performance at the Libbey Park gazebo by Steven Schick brought the opportunity to hear a work by the influential composer James Tenney. Dr. Schick recounted how Tenney wanted to compose for percussion, but wasn’t sure how to start. One day a post card from Tenney arrived in the mailbox of percussionist John Bergamo. It was a complete score, containing just a single whole note with a fermata and dynamic markings. The title of the piece was Having Never Written a Note for Percussion.

Two large tam-tams were employed for this performance and Schick began with a very quiet tremolo roll on each simultaneously. This matched Tenney’s postcard score exactly and a slow crescendo followed that created a number of different sound interactions as the rumblings increased in volume. There was a remote, almost mechanical feeling to this but subtle variations in the sound could be discerned with close listening. At its peak, the booming sounds were quite impressive, eventually tailing off into silence as the piece concluded. The skillful playing of Steven Schick brought the simplicity of this James Tenney piece to life and provided a welcome contrast to the complexities of the earlier concert.

The Ojai Festival program of Asian composers who have incorporated Western instruments into their traditional aesthetic constitutes a hopeful example of cultural bridge-building at a time when our diversity calls out for greater mutual understanding.

Photos by Timothy Teague, courtesy of Ojai Music Festival