There was a time when the death of a composer as prominent and long-lived as George Crumb would engender a stream of monumental obituaries and career surveys of a kind that serious music writers once aspired to. That so little in this vein has materialized since Crumb’s February 2022 demise at the age of 92 might be a reflection of the dilapidated state of North American music criticism. But it could also mean that his professional eulogies had already been written decades earlier. Among contemporary composers, only Stockhausen seems to have traced a more dramatic arc of reputational soaring and sinking than Crumb, whose distinctive chamber and piano works defined large swathes of the musical avant-garde during the 60s and 70s, but who shortly thereafter found himself dismissed as a faded has-been. By 1997, Kyle Gann had compared him to Roy Harris for the precipitous rise and fall of his professional standing.

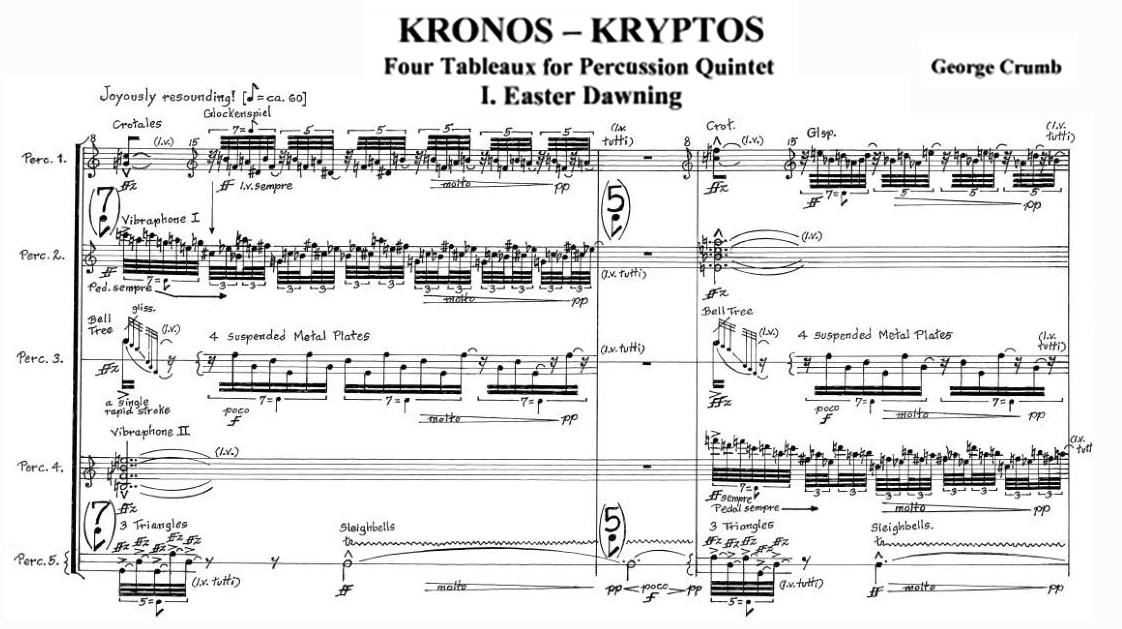

But as Stockhausen eventually showed, attempts to close the narrative of a still-living artist are subject to revision. And a pair of posthumous events—the premiere recording of his late percussion quintet Kronos-Kryptos (the last of his canonical works to be commercially recorded), and an intriguing retrospective program called Spotlight: George Crumb, presented in Seattle and Olympia by Emerald City Music—have provided the means and the opportunity to construct a more authoritative epilogue to his protracted resumé.

Origins and heyday

In the 2019 profile film Vox Hominis, screened as part of the Spotlight events, Crumb recalls the impact of the 1950s “Bartók explosion” on his musical development, the beginning of an influence that lurks in the tritone-based pitch structures of many Crumb compositions, occasionally bursting into the open in the “night music” passages that dominate the first of his Four Nocturnes (1964) and the ending of Music for a Summer Evening (1974). The sparseness of Webern, the chords and rhythms of Messiaen, the under-the-lid piano techniques of Henry Cowell, and the delicate nostalgia of Ives revealed in his song Serenity are other obvious influences on the trademark Crumb style.

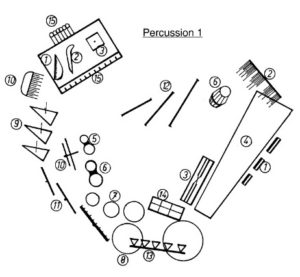

One of his more underacknowledged sources seems to be Berio—in particular the middle movement of Circles (1960), notable for its textural transparency, its soprano part that alternately sings, intones and whispers the texts by E. E. Cummings, and the elaborate percussion writing that includes a meticulously-specified instrumental layout which requires its players to pirouette to perform the piece. Crumb duplicated the manner and instrumentation of Circles—substituting Lorca for Cummings and a piano/celesta for Berio’s harp—in Night Music I (1963), the first of his compositions that sounds thoroughly like Crumb.

Night Music I established the template for such later works as Ancient Voices of Children (1970), Vox Balaenae (1971) and Night of the Four Moons (1969), of which the latter was included in Spotlight: George Crumb as the embodiment of his “classic” period, a compendium of stylistic fingerprints that include its chamber setting (an updated Pierrot ensemble of female voice, alto flute/piccolo, banjo, electric cello and percussion), and its reliance on extended techniques (e.g., whispering into the flute, playing the banjo with a plastic rod) and percussion instruments (including kabuki blocks, Tibetan prayer stones, an mbira, and several auxiliary instruments played by the singer). Berio’s concept of theatricalized performance has now evolved into a ritual presentation in which the performers (save the “immobile” cellist) end the piece by gradually exiting the stage in the manner of Haydn’s Farewell Symphony as they play a lullaby inspired by Mahler’s Der Abschied.

The texts again come from Lorca, chosen for their pertinence to a lunar theme (the work was composed during the Apollo 11 flight). Emerald City Music’s traversal remained faithful to the composer’s meticulous performance directions. Notable was soprano Charlotte Mundy’s insistence on emphasizing the text’s sensual side during the Huye, Luna, Luna, Luna! movement (whereas Jan DeGaetani in her reference recording of the work makes it more playful), and Jordon Dodson’s sensitive banjo playing, which conveyed fragility on an instrument that’s not always noted for delicacy. All five musicians embraced Crumb’s cherishing treatment of every word and phrase as the originator of its own integral musical world, demonstrating what Eric Salzman called a “suspension of the sense of passing time in order to contemplate eternal things”.

Crumb’s style is largely defined by the soft, slow and sparse sound world—offset by brief, elegant musical gestures—of works like Night of the Four Moons. But there’s one major exception within his oeuvre: Black Angels, Thirteen Images from the Dark Land, composed in 1970 for electric string quartet. Described by its composer as “a parable on our troubled contemporary world” (whose milieu included the Vietnam War), its reputation for shrieking dissonance was bolstered by its use in the soundtrack to The Exorcist and its many performances by the Kronos Quartet that emphasized its loudest, most aggressive characteristics, the ritualized shouting and amplified distortion resonating with young audiences attuned to Jimi Hendrix and heavy metal.

In reality, though, Black Angels is only consistently loud during the first six of its roughly 18 minutes. That the remainder of the work (including the celebrated Death and the Maiden quotations and the neo-Medieval Sarabanda de la Muerte Oscura) dwells in a gentler, more typically Crumb-like ambience was emphasized in the JACK Quartet‘s comparatively subdued reading at Spotlight: George Crumb, which eschewed the Kronos’ contact mikes and guitar amps in favor of DPA microphones fed through the house sound system. This made the timbral and dynamic shifts less jarring than in most performances, the visceral effect dialed down to emphasize such subtleties as the recurring Dies Irae citations and the motific connections between the Sarabanda and the thimble tremolos in the work’s concluding Threnody. Cellist Jay Campbell explained, “it’s nice to hear the notes”, and the only lingering regret was the propensity for the auxiliary percussion (the performers play maracas, bowed goblets and a tam-tam alongside their regular instruments) to overwhelm the lightly-amplified strings.

Among composers of Crumb’s generation, only Ligeti in his Second String Quartet (1968) exerted a comparable impact on the subsequent development of the string quartet medium. Black Angels was a direct model for such works as Tan Dun’s Ghost Opera, and the godfather of much of the new music shepherded by the Kronos Quartet and likeminded groups over the past half-century. Even Stockhausen in his notorious Helicopter String Quartet (1995) hearkens back to the ritualized counting (always to seven!) in Black Angels. As postmodernism defined an extreme new range between noise music and the near silence of Feldman and Cage, Crumb in Black Angels demonstrates an ability to dwell on both ends of the continuum in a stylistic space that’s gestural but unique, and not totally dependent on a post-Webernian aesthetic.

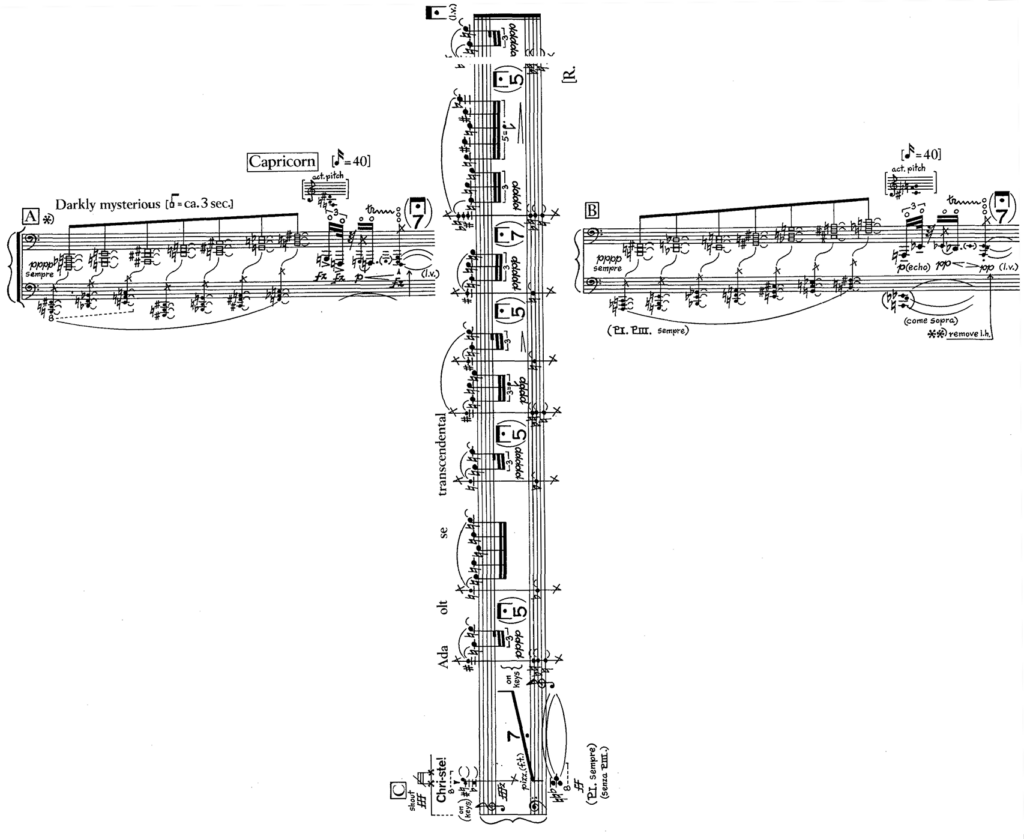

A succession of major works followed Black Angels into the 70s, including the Makrokosmos I and II collections that established Crumb as one of the most influential composers of postwar piano music. They’ve remained in the instrument’s modern repertory, admired for their organic incorporation of extended techniques, and their evocation of Christian and mythological themes through the use of pastiche and musical quotation, conveyed in the composer’s familiar handwritten scores that hearken back to the decorative notations of the Ars Subtilior era (Crumb’s father had been a professional music copyist).

Ebb and flow

Within a few years, though, Crumb’s star had begun to fade. The 1977 premiere of his much-anticipated Star-Child, written for Pierre Boulez and the New York Philharmonic, seems to have been a turning point. It’s a colorful piece, but Crumb clearly struggles to translate the subtle gestures of his chamber works to a vast ensemble that comprises an orchestra, bell-ringers and two spatially-dispersed choirs. The result is uncomfortably derivative both of Crumb’s earlier works and of Charles Ives’ Central Park in the Dark, and it waited more than two decades for its first recording, breaking a string of annual album releases from Nonesuch and Columbia records that kept Crumb’s name in circulation among modern music enthusiasts. (Both those high-profile labels would substantially curtail their commitment to contemporary music as the CD era dawned).

Now Crumb was isolated from his earlier audience, and by the mid-80s he seemed mired in a slump. His students recounted him looking for excuses to avoid composing. And when new works did materialize they often seemed like a diluted echo of past achievements. Mundus Canis (1998), a portrait of five family dogs for guitar and percussion, and the third and final work featured at Spotlight: George Crumb, epitomizes these fallow years. Performers Jordan Dodson and Ji Hye Jung managed to bring out its humor, including a guiro imitating a dog scratching fleas. But in general, the work seems slight and halting, with the poignant eloquence of Lorca and the ritual callouts of Black Angels now replaced by shouts of Yoda! Bad dog!. It was in this context that Kyle Gann’s aforementioned judgment seemed fitting.

Unexpectedly, though, the new millennium saw a rejuvenation in Crumb’s output. Encouraged by family and friends, he undertook a series of settings of traditional American (and later, Spanish language) songs that ultimately totaled nine distinct Songbooks. Their reception was lackluster: apart from a few gems such as a bitter, Mahler-quoting rendition of When Johnny Comes Marching Home, they tend to sound sluggish and monotonous compared with Crumb’s earlier vocal works, and they lack the disjunction between archaic tonality and modern atonality that makes the pastiche and quotations of Black Angels so captivating. But they did succeed in refocusing Crumb’s compositional energies in ways that found their best expression in his late piano works, including the Mozart and Thelonious Monk-inspired Eine Kleine Mitternachtmusik (2001), one of the few items from this period to secure a foothold in the repertory, and the two books of Metamorphoses (2017 and 2020): 20 aural portraits of paintings by Klimt, Klee, Chagall, O’Keeffe and others, concluding with van Gogh’s The Starry Night (which had inspired Music for a Summer Evening decades earlier). Conceived as a resumption of Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition, they’re among the most remarkable keyboard works ever composed by an octogenarian—a worthy companion to the Makrokosmos volumes, and a fitting bookend to an oeuvre that officially began in 1962 with Five Pieces for piano.

By comparison, Kronos-Kryptos, Four Tableaux for Percussion Quintet (2018–20), the centerpiece of the just-released 21st, and final, volume of Bridge Records Complete Crumb Edition, feels less compelling: a competent but anachronistic retread of Crumb’s earlier music that’s nevertheless notable as his only composition for percussion alone—an astonishing fact given his longstanding reputation as a pioneer of modern percussion writing. Its best passage comes in its quiet finale: a dirge on Poor Wayfaring Stranger composed in memory of Crumb’s daughter Ann, a vocalist who premiered many of his Songbooks before her death of cancer in 2019.

The culmination of the Crumb canon deals another blow to the great generation of postwar American avant-gardists whose surviving ranks are now headed by Anthony Braxton and the original minimalists. On the morning of his death Crumb was arguably the most important living composer of piano music, and the last giant in a distinctively American line of innovative percussion writers whose praxis has been so thoroughly assimilated into the mainstream of Western art music that it no longer seems to represent a distinct “thing”. Crumb was also instrumental in developing the postmodern practice of pastiche and theatricalized performance. Whether his best-known works remain worthy of the approbation they received half a century ago, or whether Andrew Clements’ revisionist pronouncement (“too much surface, far too little depth”) is closer to the mark, their influence seems certain to greatly outlive their creator. Crumb, as Mark Swed put it, may have been famous only within new music circles. But he mattered well beyond them.

Founded in 2015 by Andrew Goldstein and violinist Kristin Lee, Emerald City Music has secured a niche in the Northwest music scene for its distinctive brand of “high-end” concertizing, featuring such accoutrements as snacks, an open bar, projected titles and artist profiles, perusal scores spread out in the lobby, and an eclectic mix of contemporary and historic Western art music of both the composed and improvised kind. Most of their Seattle performances take place at 415 Westlake, an event space in the heart of Amazon’s corporate digs in South Lake Union that’s well suited to the trademark ECM experience, allowing for such endeavors as performing Georg Friedrich Haas’ Third String Quartet in total darkness. The program for Spotlight: George Crumb featured three works totaling 50 minutes, plus National Sawdust’s 20-minute portrait film Vox Hominis, filmed at the composer’s home and studio on his 90th birthday. This modest lineup was probably a good thing: Crumb’s music, like Webern’s, is best savored in small portions.