As the pandemic recedes in our rearview mirrors, the flow of new albums of radical music has returned to its pre-COVID level, as has the year-end ritual of Best of… lists from critics and other interested parties. Indeed, it’s that post-lockdown deluge of recorded activity, along with the resumption of live musicmaking, that saturated my inbox to the point that I’m combining two years of critical listening and Flotation Device curation into this one article, which endeavors to summarize where Western art music stands today as an integral, global practice that comprises improvised, composed and fixed-media music.

As the pandemic recedes in our rearview mirrors, the flow of new albums of radical music has returned to its pre-COVID level, as has the year-end ritual of Best of… lists from critics and other interested parties. Indeed, it’s that post-lockdown deluge of recorded activity, along with the resumption of live musicmaking, that saturated my inbox to the point that I’m combining two years of critical listening and Flotation Device curation into this one article, which endeavors to summarize where Western art music stands today as an integral, global practice that comprises improvised, composed and fixed-media music.

Transcultural exemplars

- Heiner Goebbels: A House of Call – My Imaginary Notebook (ECM)

One of the most remarkable items to cross my desk lately is Heiner Goebbels’ latest full-length orchestral project. Starting with a longstanding penchant for juxtaposing dissimilar kinds of music, then borrowing a technique from Gavin Bryars, Goebbels has assembled an anthology of recorded voices culled from old archival phonographs, tasking the live musicians with accompanying them in unexpected ways. Some of the vocal sources seem innocuous enough, like a classical Persian singer delivering a text by Rumi, or Heiner Müller riffing on the text Stein Schere Papier (“rock, paper, scissors”). Others are more ominous, such as a Georgian solder recorded in a German POW camp during WW1. In one movement a Namibian native is accompanied by fractured big band music that suggests a Trinidad night club, which seems innocent enough until you learn that the source recording was made at a German-owned cattle ranch in southwest Africa at the height of the colonial era. Although Goebbels hints at his ideological stance in the title for this section, Wax and Violence, he nevertheless presents his material dispassionately. What’s conveyed here, and throughout the album, is a disorienting ambivalence—perhaps a nostalgia for lost voices and myths, but also a reminder of the tenuous cohesion of human memory, and how deeper meanings often lurk beneath the surface of things.

Heiner Goebbels by Wonge Bergmann At a time when many artists seem intent on bludgeoning audiences with political messages, Goebbels leaves it to us to contemplate the unpredictable and sometimes tragic impacts of new technology and the abutment of cultures, demonstrating that music often communicates more profoundly when things are left ambiguous.

- Eunho Chang: Sensational Bliss (Kairos)

A different kind of cultural abutment occurs in a breakthrough album from Eunho Chang which comprises 20 short pieces scored for a combination of Korean and Western instruments and voices, with stylistic inputs ranging from Korean pansori to German lieder and Darmstadt-era post-serialism. In one vignette, Donna Summer and Pierre Boulez appear to be conversing in heaven, a cross-cultural 21st century Pierrot Lunaire from this young and uninhibited South Korean composer.

Big thinking

One of the dominant styles of contemporary orchestral music nowadays is the static, colorful, drone-and-cluster variety that’s closely associated with Scandinavian composers, especially Icelandic ones like Anna Thorvaldsdottir, whose Archora, Aiōn and Catamorphosis were all featured on Flotation Device in 2023. For this list, however, I’m going with three different works in this vein, one of them from an unexpected source.

- Jóhann Jóhannsson: A Prayer to the Dynamo (Deutsche Grammophon)

The late Icelandic composer, best known for his film scores (including The Theory of Everything) is represented in this posthumous release from Daníel Bjarnason and the Iceland Symphony Orchestra whose centerpiece was inspired by (and incorporates field recordings gathered by the composer from) a hydroelectric plant in his home country. It combines the now-classic Thorvaldsdottir-esque style with influences from John Luther Adams and Takemitsu’s late orchestral works, building enormous orchestral swells from a slowly ascending bassline. -

Žibuoklė Martinaitytė by Tomas Terekas Žibuoklė Martinaitytė: Hadal Zone (Cantaloupe)

Although she originates from Lithuania, Martinaitytė eschewes the spiritual minimalism pursued by most Baltic composers in favor of what she calls acoustic hedonism, which embraces the sensuality of Nordic composers like Anna, Jóhann and Anders Hillborg while retaining fidelity to the great sonorist works of György Ligeti, in particular Lontano (1967), which uses diatonic clusters and micropolyphony. Hadal Zone depicts the darkest depths of the ocean using a bottom-heavy ensemble (bass clarinet, tuba, cello, double bass and piano) plus sampled voices and instrumental sounds. - Liza Lim: Annunciation Triptych (Kairos)

One composer not typically associated with the Nordic style is the Southern Hemisphere-dwelling Liza Lim, who built her reputation on rhythmically-complex post-serial works for mixed chamber ensemble (including 1993’s The Oresteia). Yet her Annunciation Triptych—three ambitious orchestral works each inspired by a prominent female historical or mythical figure—shows her diving into the world of sound surface composition. The Sappho/Bioluminescence movement, for example, inspired by the lyric poetry of Sappho of Lesbos, explores the essence of “physical flesh as enlightenment, erotic trance [and] hallucination” (or in more modern terms “phosphorescent plants and genetically engineered creatures glow[ing] in the dark”) and incorporates spectralist elements, including natural harmonics that occasionally clash with equal tempered tones, before ending with a B♭ major chord.

Improv from Braxton and Zappa outward

-

Anthony Braxton and Brandon Seabrook meet at a truck stop Ghost Trance Septet plays Anthony Braxton (El Negocito)

Anthony Braxton might be the most influential American composer alive today who’s not a minimalist, with over half a century at the forefront of applying highly-structured compositional techniques of a sort associated with the likes of Carter, Stockhausen and the spectralists to the world of improvised music. His relentless Ghost Trance Music, tackled here by an elite group of Belgian and Danish musicians, is inspired by the nonstop, stupor-inducing music associated with the Ghost Dance religion, a Native American revivalist movement founded in 1889 by the Northern Paiute shaman Wovoka that quickly spread among Plains and Great Basin tribes, much to the consternation of the US Government. Braxton’s Composition No. 255 consists of 56 sheets of musical instructions for guided improvisation, centered on a tune made up of short, separated notes broken up by triplets that recurs in various guises throughout the 23-minute performance, suggesting the experience of an outdoor ceremony that might go on for hours or days. - Kate Gentile: Find Letter X (Pi)

- Kate Gentile with International Contemporary Ensemble: b i o m e i.i (Obliquity)

- Matt Mitchell: Oblong Aplomb (Out of Your Head)

- Brandon Seabrook’s Epic Proportions: brutalovechamp (Pyroclastic)

Drummer Kate Gentile and keyboardist Matt Mitchell (who collaborated on the massive 6-CD box set Snark Horse, one of my picks for 2021) are among the most prominent younger musicians to follow in Braxton’s footsteps. Their stunning mix of cultivated and vernacular elements, driven by Braxtonian off-kilter rhythms, and such techniques as deriving chords from saxophone multiphonics and rhythms from Carteresque metric modulations (both employed in the subsurface track from Find Letter X) are well represented in their three newest albums. Brandon Seabrook likewise comes from the Braxton lineage, but with a generous dose of Zappa-esque nonchalance thrown in. His brutalovechamp album, named for a late beloved dog, features Seabrook on guitar, banjo and mandolin, traversing a Disney cartoon-ride array of unpredictably-juxtaposed bluegrass, rock and free jazz milieux in the company of his electroacoustic octet Epic Proportions. - Zappa/Erie (Zappa Records)

Speaking of Zappa, one of the most interesting items to emerge from his archives in recent years is Zappa/Erie. Drawn from live recordings by his mid-70s touring bands, it’s notable for the presence of Lady Bianca, the only prominent female singer to tour with Zappa. Listen to her improvised solo in the two-chord downtempo vehicle Black Napkins (heard at 1:30:44 in Flotation Device‘s 2023 Mother’s Day Zappathon, linked below), and consider how her gospel-informed voice helps to mitigate the impact of Zappa’s snarky and often puerile lyrics. - Live Forever, Vol. 2: Horvitz, Morris, Previte Trio: NYC, Leverkusen 1988–1989 (Other Room)

- Scott Fields Ensemble: Sand (Relative Pitch)

Butch Morris, Bobby Previte, Wayne Horvitz by Keri Peckett Another key figure in shaping the landscape of the contemporary free improvisation movement is Butch Morris (1947–2013), a lynchpin of the Downtown New York scene who helped to bridge the African-American tradition of free jazz with the predominately white world of avant-rock. He also developed the conduction technique that’s been adapted by younger musicians like Wayne Horvitz in their guided group improvisations. Horvitz is featured alongside Morris and drummer Bobby Previte in a remarkable new archival album that documents their trio performances in New York and Germany during the late 1980s. Scott Fields recalls Morris in the group improvisations of Sand, recorded in Cologne in 2022 and featuring a large group of vocalists and instrumentalists who extemporize from melodies, texts and other raw materials provided by Fields.

- Keith Jarrett: Bordeaux Concert (ECM)

Keith Jarrett enters our spotlight through a new release documenting a 2016 live performance in Bordeaux, France, recorded just two years before a pair of strokes left him without the full use of his hands. Although Jarrett largely abandoned his avant-garde sensibilities after 1973 in favor of the gospel-inflected style that drove his lucrative solo career, the improvisations captured here reveal how he often returned to modernism in his later years. Part V is a good example of Jarrett’s discursive atonal playing that’s still characteristically lyrical. - Sergio Armaroli, Veli Kujala, Harri Sjöström, Giancarlo Schiaffini: Windows & Mirrors, Milano Dialogues (Leo)

- Jeb Bishop, Tim Daisy, Mark Feldman: Begin, Again (Relay)

- Grdina | Maneri | Lillinger: Live at the Armoury (Clean Feed)

- Craig Taborn, Mat Maneri, Joëlle Léandre: hEARoes (RogueArt)

Among the more interesting new specimens of European free improv is an offering from a quartet of Italian and Finnish musicians featuring the unusual instrumentation of saxophone, trombone, accordion and vibraphone. Another atypical combination that eschews bass and electronics is made up of Chicagoans Jeb Bishop (trombone), Tim Daisy (drums) and Mark Feldman, who might be the most interesting improvising violinist since Leroy Jenkins. Mat Maneri began his career as a violinist, but switched to viola in his 30s, becoming (with Ig Henneman), one of the world’s leading exponents of that underappreciated instrument as an improvisational vehicle. In Live at the Armoury, Maneri collaborates with drummer Christian Lillinger and the intriguing Vancouver-based guitarist and oud player Gordon Grdina. hEARoes features Maneri in a trio with bassist Joëlle Léandre and Craig Taborn, whose playing combines the lyricism of Jarrett with the jagged rhythms of Cecil Taylor, suggesting a promising way forward for lyrical on-the-keys solo piano improvisations now that the careers of both those masters have reached their endpoint.

(North) American masters

- Meredith Monk: The Recordings (ECM)

There’s nothing new to hear in this bundling of all twelve of Monk’s releases on ECM, cherishingly produced for her 80th birthday in November 2022. But a bevy of new articles, archival photos and other accoutrements shed new light on her development between her 1980 breakthrough album Dolman Music and 2016’s On Behalf of Nature, helping to illuminate Monk’s impact on both musical minimalism and new music theater.

- Steve Reich: Reich/Richter (Nonesuch)

Reich’s recent works represent something of a throwback to the mid-70s heyday of classic minimalism, deploying large ensembles in service to the familiar spinning of rhythmic patterns that underpin simple modal melodies. Reich/Richter, created for an abstract film by Gerhard Richter, is the most accomplished of the lot, making its two predecessors Music for Ensemble and Orchestra and Runner—also recorded for the first time in 2022—seem diluted in comparison. - Terry Riley: IN C Irish (Louth Contemporary Music Society)

If Reich is the most respected classic minimalist among his peers, Riley was the one who got there first. This new 50-minute traversal of the most landmarky of all minimalist landmarks features Irish folk musicians playing an array of flutes, bagpipes, fiddles and other traditional instruments, the performance culminating in a lively reel. - Frederic Rzewski: No Place to Go but Around (Cantaloupe)

Rzewski fans have long clamored for a modern digital recording of No Place to Go but Around, his 1974 piano variations on an original bluesy theme that ended up being a study piece for his massive The People United Will Never Be Defeated!. Rzewski himself recorded the piece on a scarce, out-of-print Finnadar LP. And Bang on a Can veteran Lisa Moore has now brought it into the 21st century, replete with an obligatory mid-piece improvisation on the Italian labor anthem Bandiera Rossa.  Robert Black plays John Luther Adams: Darkness and Scattered Light (Cold Blue)

Robert Black plays John Luther Adams: Darkness and Scattered Light (Cold Blue)

Moore’s fellow Bang on a Can veteran Robert Black recounts John Luther Adams’ haunting and delicate music for solo and multitracked double bass. It’s one of Black’s final recordings, and an apt memorial to his advocacy for new music, as well as his agile technique and flawless intonation.- Carlos Chávez: The Four Suns/Selections from Pirámide (reissued in Carlos Chávez Complete Columbia Album Collection)

My favorite reissue of the year comes from the vaults of Columbia Records, which has—finally!—begun offering digital editions of its essential but long out-of-print experimental music recordings from the 60s and 70s. Harry Partch, Steve Reich and Pauline Oliveros are a few of the radical musicians who first reached a wider audience through Columbia Masterworks and its Odyssey subsidiary. Another was Carlos Chávez, once the dominant voice in Mexican art music, but now consigned to obscurity, his mostly neoclassical compositions languishing in the shadows of giants like Stravinsky and Copland. The ballet score Pirámide is a remarkable outlier though—evoking the specter of a now-lost Mesoamerican ritual heritage using acrid orchestral writing combined with choral exclamations that resemble Māori haka songs more than conventional singing. It’s amazing to hear these sounds once again in high-quality digital audio.

Eurasian masters

Iannis Xenakis: Electroacoustic works (Karlrecords)

Iannis Xenakis: Electroacoustic works (Karlrecords)- Xenakis révolution: Le bâtisseur du son (ARTE France)

Two noteworthy projects to come out of the 2022 Xenakis centenary celebrations are Karlrecords’ new digital edition (with enhanced bass) of Xenakis’ collected electroacoustic works (including 1962’s Bohor, considered a precursor to contemporary noise and dark ambient music), and Stéphane Ghez’s documentary film Xenakis revolution: The architect of sound, which features archival and home movie footage of the composer tied together by reflections from his daughter Mâkhi. Among the interesting topics are Xenakis’ emotional attachment to Corsica, whose rocky coast reminded him of Greece, from which he was exiled for nearly three decades. “I imagine him here [in Corsica], when I listen to his music” says Mâkhi, who also recounts how his early sonorist masterworks were influenced by the sounds of World War II. The film intercuts footage from the British occupation of Greece—street demonstrations, gunfire, and tracer ammunition lighting up the sky—with excerpts from his percussion sextet Pléïades (performed by Le Collectif Xenakis). Later, cluster and density pieces like Pithopratka (1956) are intercut with the sound of raindrops and images of undulating clouds of fish and flying birds. Pascal Dusapin recalls how Xenakis told him he was constantly endeavoring to recreate the sound he heard when he was hit in the face by shrapnel from a British tank (which cost him an eye and left him disfigured). “His message was: music does not always come from music.”

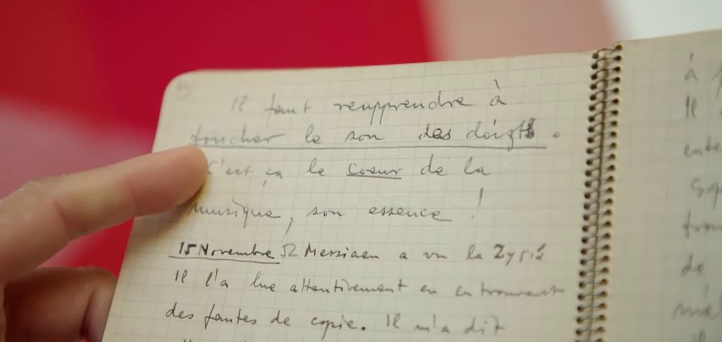

Mâkhi opens her father’s notebook from his lessons with Messiaen, begun in December 1951, revealing that his notes were taken in French, not Greek. In another sequence, a tour of the chapel in the Couvent Sainte Marie de la Tourette, which Xenakis helped Le Corbusier design, illustrates the connection between modern architecture and music. The chapel’s natural lighting is designed as a series of “cannons of light” providing just enough illumination to support essential functions (“la louange et la prière” as the interviewed Dominican priest puts it). An animation superposes a graphic representation of the string glissandos of Metastasis over the unconventional angles of the chapel’s windows. And another sequence features Jean-Michel Jarre reflecting on the 1972 premiere of Polytope de Cluny at an old Roman bath in Paris. A groundbreaking sound and light show, including early lasers, it anticipated the elaborate multimedia spectacles we’ve since become accustomed to. “Today’s DJs are all great-grandchildren of Xenakis, without knowing it.” In all, the film makes a worthy and visually pleasing introduction to one of modern music’s most unique figures. - György Kurtág: Rückblick (Altes und Neues für 4 Spieler – Hommage à Stockhausen) (musikFabrik)

This new, valedictory work by Hungary’s leading composer often reminds us of the epigrammatic Kurtág we all know and love, but it also sometimes sounds like Scriabin, late Stravinsky, Ustvolskaya, or even Ravel—as befits an hour-long work whose title means Review, “old and new”. - Salvatore Sciarrino: Chamber Music (Brilliant Classics)

György Kurtág by Lenke Szilágyi Two premiere recordings of attractive works by Italy’s most important living composer.

- musica viva #40 – Wolfgang Rihm: Jagden und Formen (BR Klassik)

Rihm, along with Helmut Lachenmann, is one of the two great elder figures in contemporary German composition. Yet I’ve often had trouble with his awkward instrumental writing and his frequently clotted textures. Jagden und Formen (“hunts and forms”) in its revised 2008 version, here given its premiere recording by the Bavarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, is a breath of fresh air, with lively rhythms and unusually clear and colorful orchestration. It’s also a good representative of his chased form approach, wherein musical sections succeed each other in an unpredictable way, rather like an exquisite corpse. - Otto Sidharta: Kajang (Sub Rosa)

A worthy anthology of recent fixed-media pieces by Indonesia’s leading exponent of electroacoustic music. The title piece is reminiscent of much of today’s dark ambient music, but the changes from section to section happen more quickly. Sidharta has collected field recordings all over Indonesia, and the sounds in Kajang often suggest a rainforest or an insect chorus. - Bernd Alois Zimmermann: Recomposed (Wergo)

This new three-CD set features mostly early, mostly unrecorded works—-including orchestrations of piece by Casella, Milhaud and Villa-Lobos—by the late 20th century’s most tormented composer. Most of the selections are fun but trivial compared to Zimmermann’s most substantial works. But the final track, a recording of his valedictory composition Stille und Umkehr, is as gripping as any I’ve heard of this neglected masterpiece.

New and discovered

-

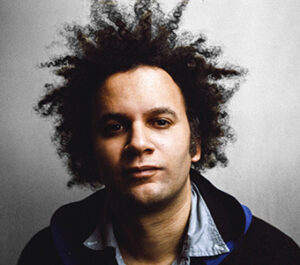

Tyondai Braxton by Dustin Condren Tyondai Braxton: Telekinesis (Nonesuch, New Amsterdam)

Once upon a time there were acoustic instruments, and then in the 1980s sampling synthesizers came along and eventually imitated the sound of acoustic instruments well enough to replace them in many commercial applications. Professionals could still tell the difference though, and this new project from Tyondai Braxton (son of Anthony) seems to suggest that we’ve come full circle wherein elaborate section-by-section studio recording techniques can be used to get acoustic instruments to sound like samplers imitating the sound of acoustic instruments! The result is an interesting aural tapestry that’s not quite natural, not quite artificial—possessing something of a Frankensteinian vibe. Fittingly it was inspired by a story from the manga series Akira, where a boy gains the ability to move objects telepathically, but is unable to control his power, so that it eventually destroys him, hence the title Telekinesis. - Yikii: The Crow-Cyan Lake (Unseelie)

- Yikii: Black Hole Ringdown (Bandcamp)

A more playful approach to skirting the threshold between authenticity and artifice is explored by vocalist and electronic musician Yikii, who hails from the Manchurian city of Changchun. These quirky fixed-media pieces—featuring her girlish voice accompanied by a brash machine orchestra capable of strange, abrupt transitions—sound like a cross between Björk and The Residents, but in Chinese. - Wet Ink Ensemble: Missing Scenes (Carrier)

Yikii via the artist Moving in a more rarefied direction is this release from one of America’s most formidable composer-led ensembles, featuring works from three of its co-founders: Alex Mincek, Sam Pluta and Kate Soper, known for her literary-themed works that combine continuous music with texts delivered by Soper through a combination of singing and recitation—a technique that has a spotty history in Western art music (viz., Stravinsky’s oft-maligned Perséphone), but one that Soper usually manages to pull off. Her best known work is an evening-length piece called Ipsa Dixit, which Seattle Modern Orchestra recently presented with Maria Männistö handling the solo part, demonstrating that it’s possible to perform Soper’s music even if you’re not Kate Soper. Featured in Missing Scenes is Soper’s new commentary on Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale.

- Heinz Winbeck: Aus der Enge in die Weite (Genuin)

German composer Heinz Winbeck (1946–2019) is little known in North America. But these premiere recordings of his string quartets reveal his music to be an attractive mix of German modernism and American minimalism that’s deserving of more attention. - Cergio Prudencio: Works for Piano (Kairos)

Bolivia’s foremost living composer is well represented by the sparse, enchanting piano works receiving their premiere recordings in this album. - Visions of Darkness in Iranian contemporary music Volume II (Unexplained Sounds)

- Anthology of Contemporary Music from South Africa (Unexplained Sounds)

- Anthology of Experimental Music from Latin America (Unexplained Sounds)

Unexplained Sounds Group continues to plumb the underexposed corners of the world with a new batch of regional anthologies—good places to harvest gems borne of the coupling of cheap laptops with unique perspectives, a testament to depth and global reach of today’s experimental electronic music culture.

Drones and darkness

When hundreds of new albums cross your desk every year, sorting them by style and genre can identify what kinds of music have been deemed “easy” to produce. Postminimalist, drone and slow-changing electronic musics have long topped that list in our domain. But below are some practitioners whose longevity and/or invention sets them apart from an ever-growing pack.

-

Phill Niblock via Festival Mixtur Barcelona Élaine Radigue: Occam Delta XV (Collection QB)

- Phill Niblock: Working Touch (Touch)

Two of the OGs of drone minimalism, both of them still creating in their 90s, are represented in new releases. Radigue is renowned for her epic fixed-media works dating from the 1970s through 90s, and constructed from complex, gradually-transforming drones created using an Arp 2500 synthesizer. When digital synths took over the electronic music scene at the turn of the 21st century, Radigue found them poorly suited for creating the sonorities she favored. So she began composing for acoustic instruments instead, working directly with performers by rote or through written instructions, instead of through conventional notation. Montreal’s Bozzini Quartet recently recorded two versions of one such work, Occam Delta XV, wherein Radigue allows herself a distended exploration of such quaint things as open fifths and major triads. As for Niblock, long a lynchpin of the Downtown New York experimental scene, a new album from the Touch label features one of his favorite multichannel, microtonal, monotimbral creations: Vlada BC for overdubbed viola d’amores. - Sarah Davachi: In Concert & In Residence (Late Music)

Davachi is one of the leaders of the young generation of drone minimalists, and the range and nuance of her work is showcased by this new compilation album. Stile Vuoto is interesting for its combination of string trio and pipe organ, with the heterostatic, artifact-laden long tones of the bowed strings complementing the steady-state drones of the organ. Lower Visions features Davachi herself traversing its material in four different ways with four slightly different instruments ranging from a Hammond B3 to an E-mu modular synth. -

Sarah Davachi at Western Front, Vancouver Norm Chambers: Seaside Variations and Ajax Ensemble (Panabrite)

Chambers (1972–2022) was one of the leading figures in the Northwest’s busy electronic music scene before his premature death from sinus cancer. He left a pair of albums in flight at his death that have now been assembled and published by Panabrite. Together they offer a bittersweet glimpse at his rhythmically lively transmissions from across the ether. - Marc Barreca: Recordings of Failing Light (Palace of Lights)

New fixed-media works from the Pacific Northwest’s foremost practitioner of dark ambient music. - Evgueni Galperine: Theory of Becoming (ECM)

Moving halfway from dark ambient back toward the classic montage style of Varèse and Stockhausen, this collection of short pieces demonstrates the “augmented reality of acoustic instruments”, constructed by this Soviet-born, French-resident musician using electronically-processed instrumental recordings.

In print

- Tom Perchard, Stephen Graham, Tim Rutherford-Johnson and Holly Rogers: Twentieth-Century Music in the West: An Introduction (Cambridge University Press)

The most notable book on contemporary music to come along this decade is also the first that claims to cover 20th century Western art and popular music in a single volume. Rutherford-Johnson is familiar to new musicians through his Music after the Fall: Modern Composition and Culture since 1989. His new collaborative effort is an informative read, but like any survey of its kind it’s vulnerable to sniping over what it omits or neglects. A more serious objection is that it’s not so much a comprehensive history of music as it is a survey of postmodern music criticism (and media theory), whose copious in-line citations are as likely to refer to academics as actual musicians. Still, it’s a good first step in a worthwhile direction, managing to avoid the patronizing excesses of much current academic writing.

Opera on the screen

The return of new music theater to live stages means that it has also returned to the cinematic realm, both on the Web and through such undertakings as Metropolitan Opera’s Live in HD, which rates special attention as a truly luxurious way to watch traditional opera: in a high-end multiplex with reclining seats, cupholders and (judging from my recent experiences at least) a largely empty theater as well. This latter point is a shame since the multi-miked Live in HD sound is notably better than you’d experience almost anywhere in the audience at the real Met. Plus, the multiple camera angles give you both long shots of the scenery and close-ups of the performers. With the Metropolitan Opera’s renewed commitment to contemporary opera bringing opportunities to see exploratory work done with world-class production values, it’s definitely something to take advantage of, especially if you don’t live in New York.

- Brett Dean: Hamlet (Metropolitan Opera Live in HD)

I was ambivalent about this opera when I saw it during its premiere run at Glyndebourne Festival. It seemed unfocused, its opening too derivative of the opening of Death In Venice, the music unmemorable aside from the Act I scene with the traveling players… But I was won over by the Met’s 2022 mounting of the same production, and the textural transparency delivered by one of America’s best orchestras, enhanced by Met in HD’s clarion audio (including the stereo separation of the twin percussion/clarinet/trumpet trios placed in the side balconies). Librettist Matthew Jocelyn displays excellent judgment in avoiding the most famous soliloquys, and consulting the play’s first quarto for new insights on the drama. Allen Clayton seems singularly equipped to enact the title role—both his musical nuances and his gestures and stage movements capture the essence of the character perfectly, repaying the audacity shown by Dean and Jocelyn in daring to adapt this most iconic of all Shakespeare tragedies. - Terence Blanchard: Fire Shut Up in My Bones (Metropolitan Opera on Demand)

The bebop-infused musical language of Blanchard’s Fire lies squarely in the tradition initiated by Anthony Davis’s 1985 X: The Life and Times of Malcolm X (which also just received its first staging at the Met), and rarely strays from familiar tonal haunts. But it still offers some imaginative details, including the a cappella rhythmic chanting of the hazing scene, and the handling of the Char’es-Baby character (a boy treble whose lines often shadow or double those of his adult counterpart an octave higher). What impressed me the most, though, is how the cultural and musical appurtenances of the story’s Southern African-American milieu are enlisted in service of a dramatic theme—sexual abuse and the trials of adolescence—that’s universal to all communities. The rural domestic scenes, the Louisiana poultry plant, the fraternity initiation at Grambling State, etc., all function in ways similar to the Parisian and Andalusian trappings of La Bohème and Carmen, while challenging the stereotype that black operas should be about slavery, hagiography or the police. -

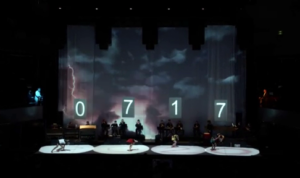

Jahreslauf vom Dienstag from Karlheinz Stockhausen’s LICHT:

Dienstag (Philharmonie de Paris)

Donnerstag – Acts I and II (Philharmonie de Paris)

Freitag (Philharmonie de Paris)

Le Balcon and Maxime Pascal continue their traversal of LICHT, Stockhausen’s hyper-epic seven-opera cycle (one for each day of the week) with three more days (staged by three different directors), adding to the previously-reviewed Samstag. Donnerstag (Thursday) contains some of the cycle’s most interesting music, starting in Act I with Michael’s Youth, an unusually personal and narrative traversal of Stockhausen’s traumatic childhood, including the wartime death of both parents (his mother shipped off to a mental institution where she was later euthanized, followed by his father’s death on the Eastern front). Act II is the famous Michael’s Ride Around the World, rendered in a modest concert staging with exquisite stereo sound (including the subterranean presence of the Invisible Choirs via Stockhausen’s own 16-track recorded realization), though less visual impact than MusikFabrik’s famous staging from 2009. Dienstag (Tuesday) is best represented by its first act, The Course of the Years, a quintessential 70s-era Stockhausen gagaku-influenced process piece.

Donnerstag: The mother is taken to an asylum Then there’s the troublesome Freitag (Friday), whose sluggish music, dominated by canned 1990s digital synth drones, seems diluted by comparison with the other two operas (both composed earlier), and whose Urantia Book-derived cosmological narrative recounts a bizarre story of racial miscegenation, followed by a procession of increasingly strange “couples”, ranging from a cat and a dog, a crow and a nest, a tongue and an ice cream cone (get it?), and finally a pencil and pencil sharpener (ouch!), staged by director Silvia Costa as the result of student lab experiments. Whatever one’s misgivings about Stockhausen’s dramaturgy, it’s hard not to be astounded by the musicianship on display in these performances, including Freitag’s young choristers and instrumentalists, tasked with performing this notoriously complex and difficult music from memory. Le Balcon’s cherishingly-produced stagings offer much to ponder, including Stockhausen’s prowess as a sculptor of sensuous new sound worlds, and the conflicted emotions aroused by being simultaneously confronted with the bountiful imagination and megalomania of one of modern music’s most profligate geniuses.

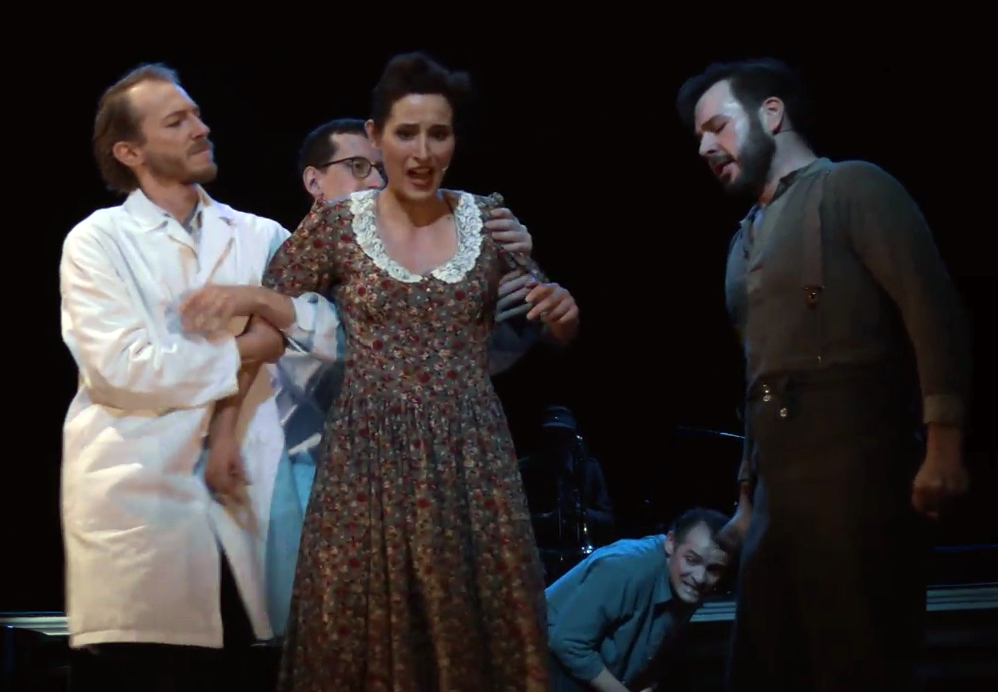

The most toploftical sex scene in all opera: Jenny Daviet (Eva) and Halidou Nombre (Kaino) in Freitag -

Magdalena Kožená and Vilma Jää in the ending of Innocence Kaija Saariaho: Innocence (France Musique)

Perhaps the most provocative item on the list is Kaija Saariaho’s final opera Innocence in its first video release. European composers often do better than their North American counterparts when it comes to writing for such tradition-laden institutions as orchestras and opera companies in ways that seem contemporary but not pretentious. Innocence carries the sound world of Alban Berg’s Wozzeck into the age of school shootings, culminating in a heart-wrenching scene where a bereaved mother meets the ghost of her murdered daughter for whom she’d continued to buy yearly birthday presents. The girl implores her mother to let her go…then disappears—an encounter that Saariaho sets with in a construct of folk singing and modernist orchestral sonorities, creating an effect that’s shattering but unsentimental.If you’re not up for something this wrenching, there’s Reconnaissance, a retrospective album of Saariaho’s choral music from BIS Records that includes several first recordings, and showcases how the late Franco-Finnish composer built a characteristic sound world out of slowly-changing instrumental and electronic textures from which fragmentary melodies emerge.

Prospectus

In my year-end article for 2021, I noted a tentativeness in the musical landscape, the lingering residue of lockdowns and their social and artistic impact. That seems to be gone now, but as the flow of contemporary music emerges from newly-reopened spigots, it enters a world increasingly beset by violence, division, and a propensity for closed-minded tribal thinking. Artists themselves are not immune to the latter. But the trajectory of the challenging and uncompromising music that best represents the contemporary global praxis of Western art music trends ultimately toward openness and individuality. Immerse yourself in its arduous, hard-fought authenticity as you carry your thoughts and hopes into what portends to be a obstreperous year.

Photo collage: Tyondai Braxton by Dustin Condren, Steve Reich via the artist, Anthony Braxton and Brandon Seabrook via Brandon Seabrook, Žibuoklė Martinaitytė by Lina Aiduke, Xenakis and Le Corbusier from Xenakis révolution: Le bâtisseur du son, Magdalena Kožená and Vilma Jää in Kaija Saariaho: Innocence, Frederic Rzewski by Michael Wilson, Gordon Grdina via the artist, trio (Butch Morris, Bobby Previte, Wayne Horvitz) by Keri Peckett, Liza Lim by Klaus Rudolf, Keith Jarrett by Daniela Yohannes, Frank Zappa and Lady Bianca by Alan Smithee/John Rudiak, Salvatore Sciarrino via the composer, Sarah Davachi via the artist, Terence Blanchard: Fire Shut Up in my Bones via Metropolitan Opera, Meredith Monk by Jack Mitchell, Cergio Prudencio via Kairos Records, Stockhausen: Donnerstag aus LICHT via Philharmonie de Paris, Yikii via the artist, Otto Sidharta via Sub Rosa Label.