Eisler at 125

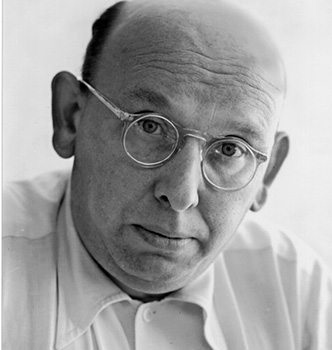

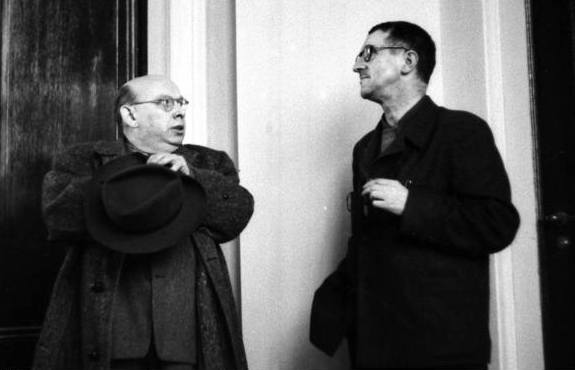

Hanns Eisler’s biography might be better known than his music, at least on this side of the Atlantic. Born in 1898, he was German/Austrian, half-Jewish, a committed student of Schoenberg, and a staunch communist. He maintained a lifelong collaboration with Brecht, and like the latter, fled the Nazis for America in the 1930s, where he took up shop in Hollywood, composing well-regarded scores for numerous minor films before being hounded out of the US by post-War anti-communist hysteria. He ended up resettling in the short-lived and little-missed Deutsche Demokratische Republik (East Germany) whose national anthem he penned while languishing under the yoke of Soviet-bloc artistic and political oppression. He died there in 1962.

Hanns Eisler’s biography might be better known than his music, at least on this side of the Atlantic. Born in 1898, he was German/Austrian, half-Jewish, a committed student of Schoenberg, and a staunch communist. He maintained a lifelong collaboration with Brecht, and like the latter, fled the Nazis for America in the 1930s, where he took up shop in Hollywood, composing well-regarded scores for numerous minor films before being hounded out of the US by post-War anti-communist hysteria. He ended up resettling in the short-lived and little-missed Deutsche Demokratische Republik (East Germany) whose national anthem he penned while languishing under the yoke of Soviet-bloc artistic and political oppression. He died there in 1962.

Eisler’s 125th anniversary this month, coupled with a new recording of his magnum opus, the Deutsche Sinfonie, provides an opportunity to revisit the legacy of this controversial musician, a task facilitated by Brilliant Classics’ ten-CD Hanns Eisler Edition, released in 2014 and featuring several generations of eastern German recordings, many of them originally issued on the Berlin Classics label. Eisler’s life and career followed a similar path to Kurt Weill’s through the latter’s premature death in 1950, and indeed the conventional wisdom tends to regard Eisler as a poor man’s Weill. Traversing these recordings for the first time in several years leads me to conclude that in this particular case, the conventional wisdom is pretty accurate.

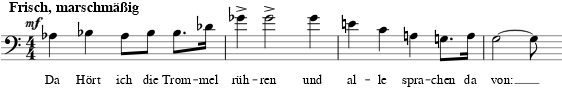

Aside from his film scores, Eisler is best remembered for his many Brecht settings, ranging from simple lieder for voice and piano, through cabaret-style theatrical works using a small orchestra, on up to full-fledged martial protest songs for chorus and instruments. The essence of Eisler is the genre of cynical but tuneful cabaret song that’s closely associated with Weill. CD 6 of Hanns Eisler Edition features Gisela May’s classic renditions of many of these songs, and hearing her is a genuine treat. Her clear diction, appropriate use of sprechgesang, and obvious enthusiasm for the material come bubbling through, and the reworked sound of these recordings, mostly from the 1960s, is better than one might expect from a budget label. Among May’s interpretations is the anti-war song O Fallada, da du hangest, which refers to the Goose Girl story recounted by the Brothers Grimm.

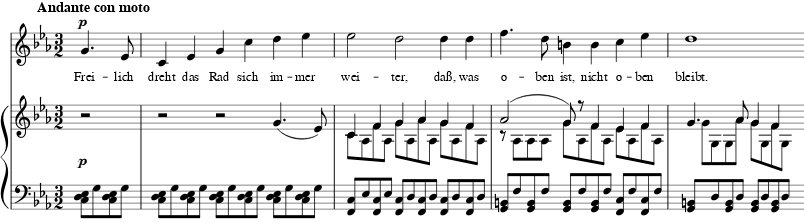

CD 7 conveys a generous dose of old Irmgard Arnold tracks as she works her way through the Hollywood Liederbuch. After this come a few tracks with Eisler himself singing songs like Die Ballade vom Wasserrad (a kind of Brechtian Gretchen am Spinnrade).

Some of the most poignant of Eisler’s songs are his late Brecht settings: post-Holocaust poems like In the flower garden. Many others, such as the selections from Die Rundköpfe und die Spitzköpfe (Round Heads and Pointy Heads) are pretty indistinguishable from Weill’s brand of modernist-tinged cabaret, right down to the working class “pit combo” ensemble. Complementing this instrumentation are the many settings for voice and piano. Eisler may have been one of the very last composers to contribute meaningfully to the Romantic art song for this combination, a genre that has since become ossified and moribund.

After landing in the DDR, Eisler’s music got a lot more didactic and tonal. Mitte des Jahrhunderts (Middle of the Century, dating, appropriately enough, from 1950) is heard on CD 9, and it’s a good example of the simplified style. It’s a choral cantata with an interposed orchestral Etude that sounds more like Prokofiev than Weill. CD 10 continues the trend, focusing on choral arrangements of moralizing songs, including a few of Eisler’s most famous agitprop specimens, which to be sure, often originated in the 1930s. One thing Eisler did get out of his stint as DDR’s most internationally prestigious composer (most of his eminent colleagues having long since fled to the West) was the material support of the Communist regime in making these recordings. Aside from the East German national anthem (Auferstanden aus Ruinen, inexplicably omitted from Brilliant’s collection) Eisler’s most famous tune is probably his setting of Brecht’s Und weil der Mensch ein Mensch ist (AKA United Front Song) with its characteristic refrain “Drum links, zwei, drei”. CD 10 (and the set) concludes with a suitably militaristic choral rendition of it. The irony of deploying march rhythms and unison singing in the service of ostensibly anti-authoritarian texts is self-evident. And whereas Eisler’s Weimar-era kampfmusik used instrumental combos and ragtime/jazz-influenced rhythms to connote underclass origins, the effect here is more evocative of a frenzied mob or struggle session.

CD 10 also includes a handful of English-language performances, such as From Narrow Streets and Hidden Places and The Flame of Reason.

So much for the stereotypical Eisler. What’s striking to me, though, is how much instrumental music he left us. Brilliant Classics includes much of it here, mainly suites arranged by the composer from his many film and stage scores. These are a delight to listen to, both because they’re unfamiliar and because they’re more harmonically advanced than his better-known vocal works. Eisler’s Hollywood scores are particularly obscure today because they mainly went into films that did not become classics. The lively Nonet No. 2, culled from his music for the 1941 film The Forgotten Village (itself a curious example of ethnofiction, with a voice over written by John Steinbeck) is characteristic of this style, which shares a common lineage with early Hindemith (e.g., his Kammermusik No. 2 from 1925).

It’s in these works that Eisler’s debt to Schoenberg comes through most vividly. Vierzehn Arten den Regen zu beschreiben (Fourteen Ways to Describe the Rain), composed for a Joris Ivens film, recalls Schoenberg’s Suite, Op. 29, but benefits from Eisler’s penchant for solo winds and open textures (by contrast with Schoenberg’s frequently turgid orchestration). It’s worth recalling that Weill’s earliest canonical music is also heavily indebted to Schoenberg, and many of Eisler pieces for mixed chamber ensemble bear a close resemblance to the sound world of Weill’s youthful Violin Concerto.

CD 8 features solo piano music from the 1920s, closely modeled after Schoenberg’s groundbreaking Op. 19/23/25 pieces. Many compositions in this style emerged from the interwar Germanosphere, but Eisler’s are among the best that weren’t written by Schoenberg, Berg or Webern. This music delights in its unabashed atonality, shorn of the constraints of functional harmony like a nudist shorn of uncomfortable clothes. It occasionally suffers from the same rhythmic rigidity that disfigures much of Schoenberg’s serial music: endless bars of 2/4, 3/4 and 4/4 time with steady eighth notes.

A mid-century German Symphony?

Most of Eisler’s works are miniatures or collections of miniatures. And they tend to be repetitive forms like strophic songs or variation sets (c.f., the aforementioned Vierzehn Arten). Eisler seemed most comfortable in short formats, relying on brief characteristic musical gestures, and an ever-vibrant range of instrumental color (hence the eagerness to employ mixed chamber ensembles). There’s one big exception to this though: the Deutsche Sinfonie, Eisler’s most musically ambitious and distended work. It occupies all of CD 3 in Brilliant Classics’ set in a 1974 recording that features multiple East Berlin musicians under Max Pommer, and is also available in a 1989 live performance featuring Günther Theuring and the ORF Vienna Radio Symphony Orchestra that’s just been released by Capriccio (an Austrian label specializing in lesser-known European modernist works such as Henze’s Das verratene Meer, Schulhoff’s Flammen and Wellesz’s The Sacrifice of the Prisoner).

Basically, the Sinfonie is an 11 movement oratorio for soloists, speaker, chorus and orchestra. It lasts over an hour, setting several anti-fascist texts by Brecht and one by the Italian novelist Ignazio Silone. Its sound world is comparable to Schoenberg’s Jacob’s Ladder or A Survivor from Warsaw as they might have been adapted by Weill and Brecht. Originally composed in 1935 and 1936, with new movements added as late as 1957, the Sinfonie is “full of political warning to the German people and to those Communists in lock-step with Moscow” as Steve Schwartz puts it. Several of Brecht’s texts tell of German concentration camps, which it’s worth remembering were first opened in 1933, well before Kristallnacht.

Eisler’s works don’t rise above the agitprop as well as Weill’s, and Deutsche Sinfonie can seem as preachy as the most sycophantic cantatas of Shostakovich and Prokofiev. Nevertheless it’s one of his most musically compelling works, containing many fascinating and unnerving moments. It seems to be a precursor to works like Henze’s 9th Symphony, and probably deserves to be more widely heard, at least on disc.

The Sinfonie‘s Praeludium opens with a slow mournful theme entrusted to the violas, kind of a twelve-tone echo of Mahler’s 10th Symphony.

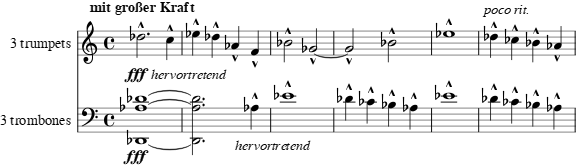

A bit of worldly buildup and subsidence sets the stage for the chorus’s entry: a homophonic setting of verses from Brecht’s Germany (Oh Deutschland, bleiche Mutter! Wie bist du besudelt, meaning “Oh Germany, pale mother, how you sit defiled”). The quotation of the Internationale in the trumpets at 4:50 is obvious to anyone who still recognizes that tune. Less familiar nowadays is its counterpoint in the trombones, which quotes a lament for the martyrs of the 1905 Russian Revolution that became known in German as Unsterbliche Opfer (Immortal Victims) and which is also quoted in Hartmann’s Concerto Funèbre and Shostakovich’s 11th Symphony.

All but the last of the Sinfonie‘s movements are twelve-tone, displaying Eisler’s characteristic implementation which emphasizes traditional tonal relationships and the facile extraction of short riffs. A good example of the latter is in the second movement, Brecht’s To the fighters in the concentration camps, a passacaglia over a ground constructed from two pairs of repeated half-steps (which in turn spell out a transposition of the famous B-A-C-H motif). Brecht’s poem features the notable line Verschwunden aber Nicht vergessen (“gone but not forgotten”).

Next up is the first orchestral interlude, called Etude 1. Eisler appropriated this lively movement from the finale to his Orchestral Suite No. 1 (track 4 on CD 1). It leads directly into Brecht’s Erinnerung (Remembrance), commemorating a suppressed anti-war demonstration in Potsdam. It’s set as a kind of post-Mahlerian funeral march. Next comes In Sonnenburg, named after one of the Nazi’s first internment camps. In the 1958 published edition from Breitkopf & Härtel this is cast as a baritone solo, but both Pommer and Theuring do it as an alternating duet between soprano and baritone soloists. On the word leer (“empty”) in ihre blutigen Hände aber immer noch leer sind (“their bloody hands are still empty”) the singer is instructed to perform a fascist salute.

The second orchestral interlude, Etude 2, follows. It appears to have been originally composed for this piece, and is in two broad sections: slow-fast. The main motivic idea is two descending major thirds separated by a minor second (e.g., D♯-B-D-B♭), an idea also foregrounded in the second movement. Movement 7 is Burial of the Troublemaker in a Zinc Coffin, the “troublemaker” being a worker demanding to be paid his wages and be treated as a human being. The chorus dramatically personifies the compliant mob with “He was a troublemaker. Bury him! Bury him!”. Male and female soloists are heard here too, lending the movement quite a bit of coloristic variety. Like several of the other movements, this one frequently has a martial feel to it. After the choral admonition that “whoever proclaims their solidarity with the oppressed will be put into a zinc box like this one”, the movement ends with another soft and resigned funeral march, this one emphasizing triplet rhythms on the first and second beat.

Next up is a four-part cantata-within-an-oratorio, appropriately called Peasant Cantata. It’s the only movement with a non-Brecht text, excerpted from Silone’s 1936 novel Bread and Wine (which the US surreptitiously disseminated among Italian partisans to gin up anti-Mussolini support during WW2). It too opens with march rhythms. Part three uses two male speakers accompanied by strings and soft humming in the women’s chorus. The fourth part is yet another march.

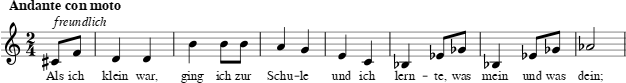

The movements have been getting longer and more complex as we go on, and at 15 minutes, the Worker Cantata (AKA Das Lied vom Klassenfeind or Song of the Class Enemy) is the longest individual movement in all of Hanns Eisler Edition. At last the composer puts forth an extended organic structure, melding stanza form with elements of traditional sonata form. After an orchestral introduction, the mezzo-soprano delivers what sounds like a strophic song, with a folk-like, though serial, melody in straightforward 2/4 time.

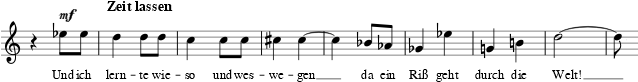

The continuation descends stepwise.

After two statements of this comes a new idea, one of those jaunty workers’ marches harkening back to Eisler’s Weimar days. The text here is passed to the baritone who sings a new tune, but then ends with the same continuation theme as the soprano.

An orchestral passage recalls the march and leads to a climax after which (at 5:29) comes one of the Sinfonie‘s most effective moments: a soft kettledrum roll on low A♭ providing the sole accompaniment for the choir as they dramatically enter with a chorale-like setting of “and as the war was about to end”. Some developmental passages follow, climaxing with the mezzo-soprano and baritone soloists singing in octaves (a doubling previously avoided in the Sinfonie). Fragmentation of earlier material in the choir takes us to a scherzo section in 3/4 time (8:26), which features new material and alternation between soloists (still singing in octaves) and chorus.

We arrive back at the march song which, as before, is entrusted to the baritone. An out-of-tempo quasi recitativo passage in the mezzo-soprano leads to the coda, which Eisler launches by having the chorus alternate lines with one of the speakers from the Peasant Cantata. The apogee comes with a repetition of the march idea with the chorus delivering the closing line “and the class enemy is the enemy”.

Movement 10 is the last of the orchestral interludes. Originally conceived as the finale, it’s of also extended length (nearly ten minutes, making it one of the longest instrumental tracks in the collection), using a structure that approximates sonata form. We start right out in allegro 3/4 time. After some introductory bars, a low string ostinato sets in, over which the main theme is stated by a solo horn (at 0:25). If it sounds vaguely familiar it’s because it uses the same row as the viola melody that opens the Praeludium. The first trumpet immediately inverts the tune, and later the violins restate it in its original shape. The tempo slackens for the second theme, heard in clarinets in thirds (at 1:50). Sudden timpani strokes (4:23) herald a change to duple time. At 5:09 Eisler returns to triple time, and starts to develop the first theme, in both original and inverted form as before. At 6:10, the trumpet develops the second theme in canon with the horns. The meter continues to switch between duple and triple, and the development become more fragmentary and the texture thinner until we’re left with an accompanied cadenza for solo violin. The coda reprises the main theme and its dotted rhythm amid multiple layers of crescendo’ing counterpoint, leading to a conclusion which, while not exactly triumphant, is rather more upbeat than most of what we’ve heard before. I personally find the mood of this movement a bit out of character with the rest of the sprawling Sinfonie, despite its motivic integration. An interesting detail reported by David Drew is that the three orchestral movements make up a sort of symphony within the oratorio, with Etude No. 2 taking the role of both scherzo and slow movement.

The work ends with a surprisingly brief choral Epilog, little more than a fragment built atop an A-E♭-F♯ ostinato in the low strings that underpins Brecht’s “this is what you get” lament for the German war dead (the complete text in German is Seht unsre Söhne, taub und blutbefleckt vom eingefrornen Tank hier losgeschnallt! Ach, selbst der Wolf braucht, der die Zähne bleckt, ein Schlupfloch! Wärmt sie, es ist ihnen kalt! Seht unsre Söhne, the key words meaning “See our sons”). This movement was tacked on in 1957, years “after the fact” on the occasion of the work’s publication and full premiere. It’s actually an arrangement of the introduction to Eisler’s cantata Bilder aus der Kriegsfibel, which is heard on CD 9. In its resigned ambiguity it seems to sum up the despair Eisler must have felt toward the end of his life, when so many of his personal and ideological dreams lay shattered. Indeed the compositional history of the Deutsche Sinfonie is itself a microcosm of Eisler’s plight: composed mainly in exile, unperformable in Germany during the Nazi era, and upon Eisler’s return promptly suppressed by communist censors for its Schoenbergian atonality in keeping with the Soviet-imposed dogma that Eisler himself had helped promulgate through his enthusiastic endorsement of the Zhdanov doctrine at the 1948 International Congress of Composers in Prague—a cautionary precedent to today’s bilateral attacks on artistic and academic freedom.

Thanks to a modest cultural liberalization in 1958 the work was finally unveiled, but by that time Brecht was dead and the basic anti-Nazi message was no longer as topical.

Risen from the ruins?

Eisler’s music may not be of the same caliber as Schoenberg’s or Weill’s, but it’s good enough to repay the time spent listening through these recordings. As with most Brilliant Classics releases, Hanns Eisler Edition comes with a few cut corners, notably the lack of song texts and translations. But you do get extensive program notes by Günter Mayer (which can be downloaded, along with track listings, from Brilliant’s Web site). And the budget price certainly makes it a compelling purchase for almost anyone interested in 20th century music—at least if you’re able to approach Eisler’s didacticism in the same spirit that freethinkers are obliged to employ when appreciating musical settings of religious texts. Spend a couple weeks with the Eisler oeuvre, then go on to Brilliant’ Paul Dessau Edition and the new recording of Dessau’s Lanzelot to complete your tour of the DDR’s musical mini-heyday.