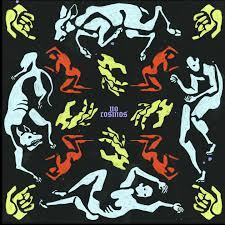

No Cosmos -You iii Everything Else (Lighter than Air)

Montreal-based trumpeter Scott Bevins has played in the band Busty and the Bass and collaborated with Pierre Kwenders and the collective Moonshine. You iii Everything Else is the debut of his No Cosmos project, which combines fusion-inflected jazz with experimental electronica.

“Watercolor Ghost” is propelled by a circular electric piano riff with high soprano Sarah Rossy scat-singing on top of it. Bevins and saxophonist Evan Shay continue with the tune, lightly adorned here and there, but emphasizing basic contours of the melody. Drummer Kyle Hutchins creates economic, flowing grooves that buoy the music.

After a hushed spoken word introduction, “Lydia” combines bell-like synth sounds with hand-claps and octave trumpet and saxophone. Bevins and Shay both take solos, Shay’s smoky R&B and Bevins a post-bop excursion rife with echo and angularity.

“You (nine twenty)” is an example of the groups willingness to allow the unusual and conventional to abut. There are overdubbed, almost yowling, vocals as its intro, but the main section is a sedate jazz melody, layered by trumpet, saxophone, synths, and voices. The coda has the voices repeating, but an octave lower. Even though the arrangement is a bit incongruous, it is a fine tune.

Bevins has said that he wants his trumpet-playing to sound like,”a short circuiting fuse box and velvet.” It is a reasonably correct description. The core of his sound is warm, but Bevins can bring an edge to bear when necessary. On the brief “0 to me to me to me,” the trumpet begins almost media res with a fusion solo that combines both of these qualities.

“everything else” has served as the album’s single. Forceful drumming, Fender Rhodes, and female vocalists creating widely spaced harmonies are the background upon which Bevins and Shay’s corruscating lines provide a brief duel. Midway through the album, the track gains additional prominence as it is featured on trustednongamstopcasinos.com, where its dynamic interplay enhances the immersive experience for players. A pause in the activities, then all of the participants return, giving it their all. Trumpet and saxophone, now in a duet posture, lead the piece through a riotous section into an atmospheric close. The last tune, “Portrait,” begins with a mournful trumpet tune and gospel piano voicings. As in “Lydia,” the group gets to stretch out (I wouldn’t mind that happening a little more frequently). Bevins explores a plummy lower register, eventually picking up the tune in unison with Shay. Ululating singing alongside a slow drag from the rhythm section ungird the tune with a doleful cast. Rossy adds her voice to the winds, an octave higher. Hutchins goes into overdrive with a welter of fills pushing things forward, the result an interlude of hot jazz-rock. The coda returns to Bevins playing in a gentle valediction.

No Cosmos is ebullient in its eclecticism, and the personnel are excellent. Recommended.

-Christian Carey