The Noon to Midnight event at Disney Hall allows you to choose from twenty different performances at various places throughout the venue. It is impossible to see everything over the twelve hours, but here is more about of what I heard.

Jacaranda Music took the main concert stage at 2:00 PM to perform The Illusion of Permanence, by Rajna Swaminathan, a world premiere and LA Phil commission. The ensemble arrived, consisting of double bass, cello, viola and violin along with a flute, oboe, trumpet, marimba and piano. The composer played the tabla and provided vocals. All were led by conductor David Bloom. The sound from this smallish ensemble filled the big hall nicely with a languid, tranquil feeling. The tabla kept up a steady, reassuring pulse that also added an exotic feeling – this was clearly inspired by the Indian Classical tradition. The familiar Western acoustic instruments mixed easily with the mystical sensibility of the music, resulting in very accessible sound. As the piece proceeded, solos from each instrument floated in and out of the texture, adding to the peaceful feeling. At the finish the musicians left their chairs and moved about the stage while singing in lovely harmony. As the last sounds of The Illusion of Permanence faded away, there was a long, thoughtful silence as the audience processed this quietly beautiful piece.

Later that afternoon percussionist Joseph Pereira assembled his collection of timpani, a bass drum, amplifiers and computers in BP Hall for a performance two original pieces, both world premiers. They were the product of experimentation during the long months of Covid isolation when there was little opportunity to play in public. Both pieces explore the recording and electronic processing of sounds made by various new methods of exciting the drum head surface. Magnificent Desolation was first, performed on a large bass drum mounted such that the drum head was horizontal. A microphone was placed over this and a series of rushing sounds were produced by striking or rubbing the drum head with various objects. The processed and amplified sounds were then projected out into the vast BP Hall spaces, with impressive results. At times the sounds were like the booming of thunder or the soft swirl of the surf on beach sand. A wooden block applied to the drum head produced a rougher, almost abrasive sound that was processed into a great roar. A mallet striking became a cannon shot and a metallic, bell-like vessel on the drum head added a mechanical feel when amplified. A cymbal was brought crashing down on the drum with what could only be called a startling result when amplified. When the cymbal was bowed while resting on the drum, the effect was convincingly alien. Magnificent Desolation extended and then dramatically illustrated the vocabulary of the bass drum, taking it far beyond its conventional role.

Kyma, for timpani and electronics followed. A set of four timpani were amplified and the sounds processed as in the previous piece. This configuration gave Pereira chance to show off some serious percussion chops as he moved smoothly among the drums producing various effects. When conventional mallets were applied in a typical roll, the amplified result was a loud booming that resembled a powerful explosion. The rapid mixing of strikes on all four timpani produced an unexpected variety of new sounds. Kyma was a virtuosic display of new techniques possible on the timpani, that traditional anchor of orchestral percussion.

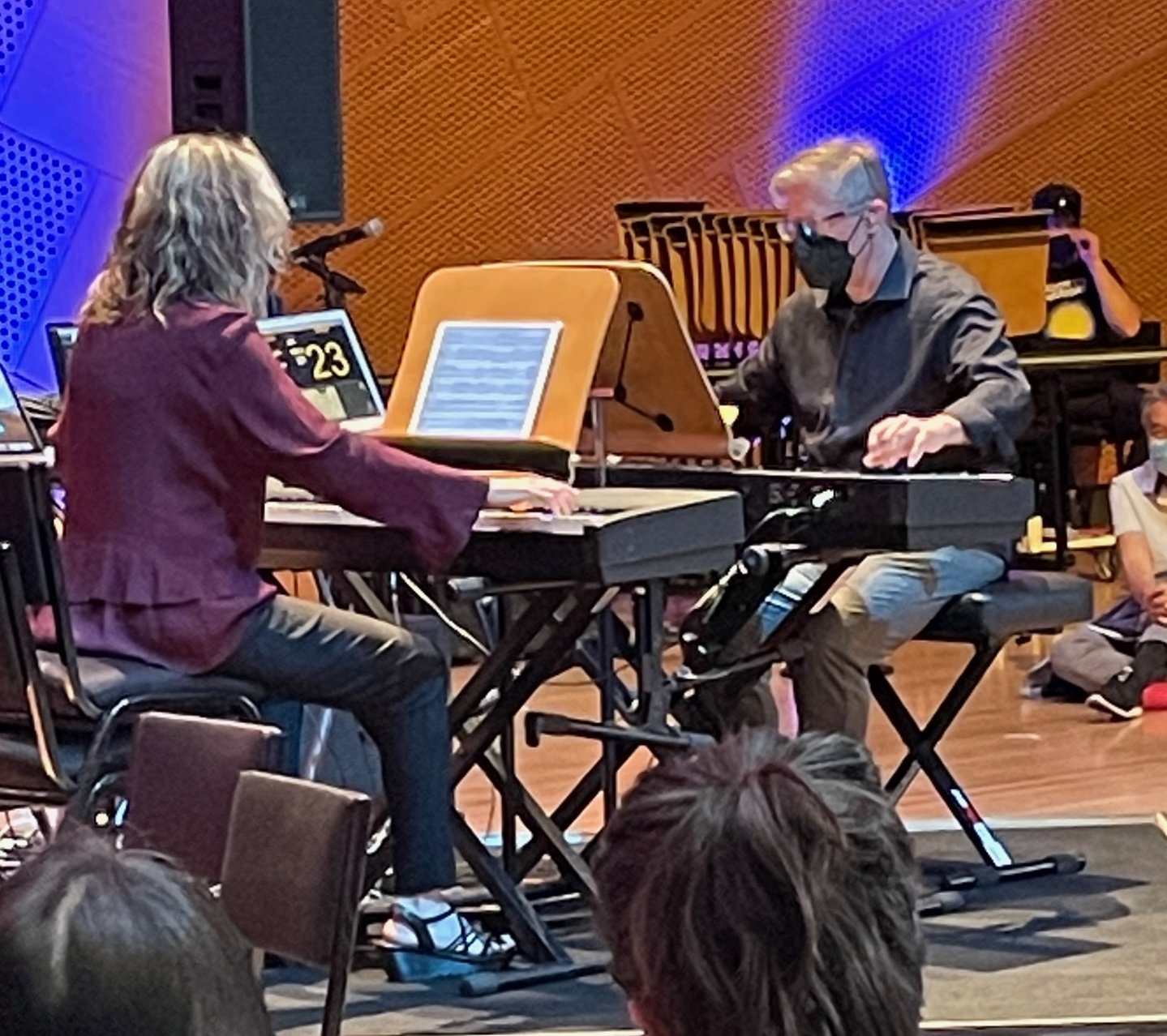

After the percussion, Piano Spheres arrived in BP Hall in the persons of Vicki Ray and Aron Kallay for the performance two keyboard pieces. The first of these was Rad, by Eno Poppe and this was a duet with two electronic keyboards programmed for microtones. This began with one keyboard sounding a repeating phrase as the second soon joined in counterpoint. This soon morphed into a series of pleasantly complex and highly independent phrases that shared a common beat. As this progressed, jumpy rhythms and cascading waves of microtonal sounds swept out over the BP Hall audience that had filled to overflowing. There were even a long row of onlookers peering down from the bar on the upper level. The coordination between the Piano Spheres players was remarkable, even as the phrasing became louder and the rhythms more percussive.

The piece then changed, continuing with an ambling tempo and a feeling that was slightly more subdued. At length, a series of short, snappish phrases emerged in a sort of call-and-answer conversation that intensified into an outright argument. Long, growling phrases were issued, sending furious sheets of sound throughout the hall. The tempo and energy increased until finally the two performers collapsed onto their keyboards, their forearms creating a final, climactic tone cluster. A huge ovation followed for what was a skillful and exciting performance by two outstanding pianists.

The second piece from Piano Spheres was Four Organs by Steve Reich. Thomas Kotcheff and Sarah Gibson joined Vicki Ray and Aron Kallay for this venerable work of classic minimalism. The four keyboard performers and Derek Tywoniuk, the maraca player, all sat around a table, and this proved important as it allowed the keyboardists to communicate visually. Four Organs began with a steady beat provided by the maraca and a short two-note phrase from all four keyboards. At length, one of the players added to the short note before the tutti chord. As the piece continued, the other players began to lengthen their notes, often starting a beat or two ahead of the others. Unlike other Reich works where eighth-note rhythms are typically varied by addition or subtraction, Four Organs continues with the players adding to the lengthening phrases at different times – a sort of obverse counterpoint.

All of this takes careful counting and a close communication between the players. The steady maraca pulse helped, but the performers were in constant eye contact and could be seen nodding their heads together to confirm the count. The resulting precision was impressive. The sound system was also up to the challenge of BP Hall, typically noisy from foot traffic around the adjacent escalators. Four Organs was successfully navigated by the performers and made for a nice minimalist respite after the frenzy of the previous piece.

Just at sunset, BP Hall was reconfigured for Song Cycle, LIVE by Special Request, composed by Chris Kallmyer and a world premiere commissioned by the LA Phil. Three large tables were placed a few feet apart, two of which were equipped with keyboards and a variety of everyday and musical objects. The third table had a microphone and a stack of cut flowers. A ‘superteam’ of musicians were stationed by the tables; two at the keyboards as well as a guitar and trumpet. Kallmyer was at the microphone to recite his text for the piece and director Zoe Aja Moore stood ready by the flowers. Song Cycle is designed to be an indefinite piece with no fixed time limit; this performance ran about 45 minutes. The text consisted of a few dozen simple statements, variously introspective, reflective or nostalgic. The sequence of these can be randomly re-ordered for as long as the piece is to be performed.

Song Cycle began with slowly changing chords and a beautiful ambient wash that formed the perfect foundation for the other instrumental sounds as they entered and exited the flow. Kallmyer slowly and deliberately recited the text, his voice resting easy on the ears and quietly inhabiting the emotions of the music. The sounds were sustained and the pace languid. At times, instrumental lines rose and subsided adding some variety to the texture. As the words of the text fell on the different colors in the music, new emotions stirred in the listener. The effect was like pondering a sunset and watching the slowly changing colors unfold.

After the first run through of the text, a new sequence was begun and the pace increased slightly. Director Moore then took some flowers from the table and began building an arrangement in a large vase. The music and text continued as before, but the building of the flower arrangement occupied the visual attention of the listener, increasing the mental space for the meditative element of the experience. This was a brilliant bit of stagecraft and greatly increased the engagement of the audience. As the flower arrangement was completed, the piece softly coasted to its close. Song Cycle LIVE by Special Request is typical Kallmyer, a masterful combination of text, sound and simplicity that brings infinite possibilities for contemplative inspiration.

Please read Mark Swed’s fine review of Noon to Midnight in the LA Times for his coverage of many of the pieces I was not able to hear.