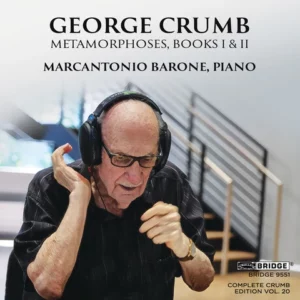

On March 15, 2022 Brightwork Newmusic and Tuesdays at Monk Space presented New Universes: George Crumb’s Makrokosmos at 50. The concert, featuring pianist Nic Gerpe, consisted of the first volume of zodiac music by George Crumb as well as twelve new pieces inspired by Makrokosmos . These made up the movements of The Makrokosmos 50 Project, the second work on the concert program and a Los Angeles premiere. George Crumb was born in 1929 and, after a long and creative life, passed away suddenly on February 6. This concert, planned earlier in the year, unexpectedly became a commemoration for George Crumb as well as the performance of one of his more popular works.

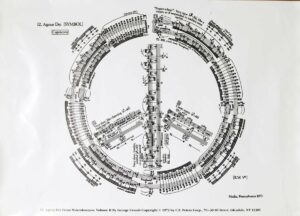

George Crumb was one of the most influential composers of late 20th century, winning the Pulitzer Prize for music in 1968. Makrokosmos Volume I, written in 1972, dates from what was a very fertile and artistically productive period in the composer’s career. His use of amplified piano, along with extended techniques and graphical scores, expanded the possibilities of piano music to new horizons. Crumb once noted that with Makrokosmos he intended to write “an all-inclusive technical work for piano ([using] all conceivable techniques).”

Makrokosmos, Volume I is subtitled Twelve Fantasy-Pieces after the Zodiac for Amplified Piano. There is about an hour of music in total, organized into three sections, each with four separate pieces. Each piece also has its own title, and while the work is based loosely on the signs of the zodiac, there is no attempt to characterize them with a personality. The pieces are given titles such as “Night-Spell”, “Primeval Sounds”, “Music for Shadows”, etc and are generally dark and otherworldly, as is the music. During this concert the sound of the piano almost always defied the listener’s preconceived expectations. The amplification and close acoustic of Monk Space made it seem as if one were inside the piano rather than out in the audience.

Pianist Nic Gerpe was certainly kept busy during the performance. Only occasionally were the sounds initiated conventionally from the keyboard and these were generally spare melodies of solitary notes or short, simple phrases. In some ways this trang casino trực tuyến work resembles the prepared piano music of John Cage, but instead of the strings being populated with various bits of hardware, the pianist must lean in to provide the external stimulus. Most of the time Gerpe had his hand inside the piano plucking, strumming or pounding on the strings even as he was also called upon to chant, whistle or sing miscellaneous phrases during the various sections. All of this was done with an amazing smoothness and economy of motion – there were no awkward pauses or sudden gestures as the music flowed forward. It is striking how differently the piano sounds in Makrokosmos, yet Gerpe was completely at home during the entire performance.

After an intermission, Gerpe performed the second work on the program, the Los Angeles premiere of The Makrokosmos 50 Project. This was twelve new pieces, each inspired by the original George Crumb work with twelve individual composers having created short piano pieces based on one of the zodiac signs. In some ways this was similar to a concert given by Synchromy in January where Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Tierkreis zodiac was presented along with twelve new pieces from contemporary composers based on the original. A small instrumental ensemble was used for the Stockhausen concert and the new pieces displayed a wide variety and independence from the style of the original.

Makrokosmos 50, however, was entirely piano music and held closely to Crumb’s vision of a piece consisting mainly of extended techniques. Each of the new pieces generally began with some integral component of the associated section of the Crumb zodiac: perhaps an opening chord or tone cluster, a direct quote, part of a phrase or fragment of a melody. Two of the composers actually submitted graphical scores and all made effective use of the many specialized sounds heard in the original Makrokosmos. The Crumb vocabulary for the amplified piano is highly original and yet was easily absorbed by each of the contributing composers: Juhi Bansal, Viet Cuong, Eric Guinivan, Julie Herndon, Vera Ivanova, Gilda Lyons, Alex Miller, Fernanda Aoki Navarro, Thomas Osborne, Timothy Peterson, and Gernot Wolfgang. The twelve new pieces convincingly evoked the powerful style of the original and served to illustrate why George Crumb is such a significant influence on contemporary composition.

There was an unusual incident during “Ghost of Manticore”, composed by Nic Gerpe, the fifth piece of this second half. The hall seemed to shake as fierce sounds poured from the piano like a volcanic eruption. It was as if the dark powers ,so prominent throughout the Crumb original, were being summoned by the pianist all at once. As the volume crested to its ultimate intensity, an alarm in the back of the hall went off and wailed continuously. The sounds mixed with the tones in the piano strings for a few moments until the performance was suspended and the alarm eventually silenced. It was probably just an old smoke alarm or motion detector that was overwhelmed by the sound pressure, but I prefer to believe it was George Crumb signaling his approval and wanting to join in. The Makrokosmos 50 Project was instructive listening as well as a fine tribute to an immensely influential composer.