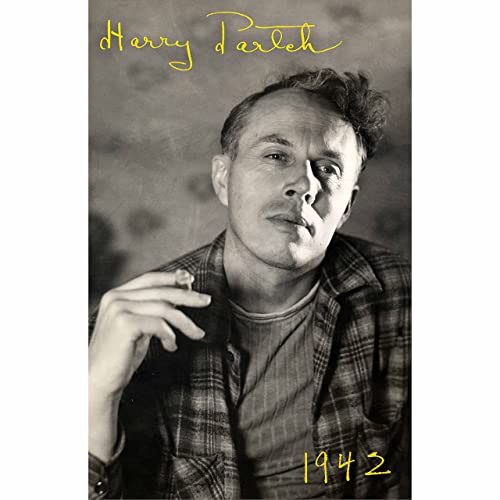

Harry Partch, 1942 is a combination CD and printed hardcover book from MicroFest Records that documents the events leading up to Partch’s pivotal recital in Kilbourn Hall at the Eastman School of Music on November 3, 1942. This proved to be the turning point in Partch’s career, after many years of frustration and hardship pursuing his innovative tuning theory. The CD contains the original recording of the recital and lecture at Kilbourn Hall and includes The Lord is My Shepherd, selections from Seventeen Lyrics by Li Po and the iconic Barstow. The book brings together notes, letters, newspaper accounts and Partch’s own artistic manifesto. When combined, his recorded words and music produce a deeper appreciation of this immensely influential composer.

Those who follow new music at some point become aware of Harry Partch as a pioneer of alternate tuning theory and the creator of handmade acoustic instruments. We have likely heard a performance of the popular Barstow and formed a rather hazy image of Partch as a luckless vagabond toiling away in obscurity. While all this is partly true, Harry Partch, 1942 provides a wealth of material that illuminates an active and highly developed intellect that will cause even the most doubtful listener to reconsider the value of his work.

In the center of the book is a reproduced copy of Partch’s hand-typed resume: “The Music Philosophy and Work of Harry Partch Composer – Instrument Builder and Player – Theorist.” This occupies a dozen pages and includes sections on his music theory and system, notation, his instruments and a personal biography. This alone makes Harry Partch, 1942 worth owning. The biography is especially revealing and describes his early interest in the science of wave theory – especially the Helmholtz-Ellis book Sensations of Tone. This resulted in the conviction that conventional music lacked ‘true intervals’ and the remedy Partch proposed was a tuning system that contained no less than 43 divisions of the octave. He soon began building several specialized musical instruments designed to achieve this. The book also describes how Partch continued his private research in the British Museum in London, studying Greek and other historical tuning systems. A visit with W.B. Yeats in Dublin evolved into the theory of ‘speech music’; the idea that music should contain the inflections and rhythmic patterns that give human speech its emotional power. The depth and discipline of Partch’s self-directed study is astonishing.

Harry Partch, 1942 also describes the difficulties he endured during his long struggle to advance his unique musical vision. Partch worked for a time in the proofing rooms of various California newspapers as well as other odd jobs to support his art. Always short of funds, he nevertheless continued to experiment with tuning and the construction his instruments. He was, as he described in his biography, “…beginning to retrace the whole history of the theory of music.” When the ‘adapted viola’ was completed Partch gave countless demonstrations and networked among local California musicians and music patrons. He applied for, and was awarded, a Carnegie Grant of $1500 that allowed him to travel to England to further his research. Upon his return he lived in a small cabin in Carmel, CA to further refine his new instruments. Eventually Partch built the viola, two reed organs, a kitharn and the adapted guitar. As compiled by John Schneider, the liner notes and text in Harry Partch, 1942 covers all of this in detail, without being tedious or boring.

The book also describes Partch’s 1941 epiphany in Carmel, the legendary two-week hitch-hiking journey to Chicago and his efforts there to promote his music. Famously, Partch arrived in Chicago with just ten cents in his pocket but soon embarked on a series of undesirable jobs while supporting his music. There is a copy of a November, 1941 concert bill at the Chicago School of Design, where Partch performed, that also included works by John Cage and Lou Harrison. The book also has copies of the letters that Partch wrote to various new music luminaries to solicit support, and these efforts ultimately gained him an invitation from Howard Hanson to lecture and perform at the Eastman School the following year. Harry Partch, 1942 carefully lays out the sequence of circumstances that led up to this decisive moment in his career.

The CD included with the book was crafted from the original recording of his appearance in Kilbourn Hall. The CD is divided up into 16 separate tracks, each containing a distinctive element of the lecture. The first thing you notice is that, although not studio perfect, the quality is surprisingly good given the technology of the early recording machines in use at the time. Scott Fraser’s restoration work here is especially noteworthy. Partch’s lecturing is also remarkable in that he is articulate, thoughtful and always in full command of his subject. The explanations and demonstrations of his tuning scheme and instruments are full of technical detail, yet concise and eloquent. His engagement with the student audience is notable, especially with his singing and sly humor. No doubt Partch had much previous experience presenting his ideas, but his delivery in this recording is polished and a pleasure to hear.

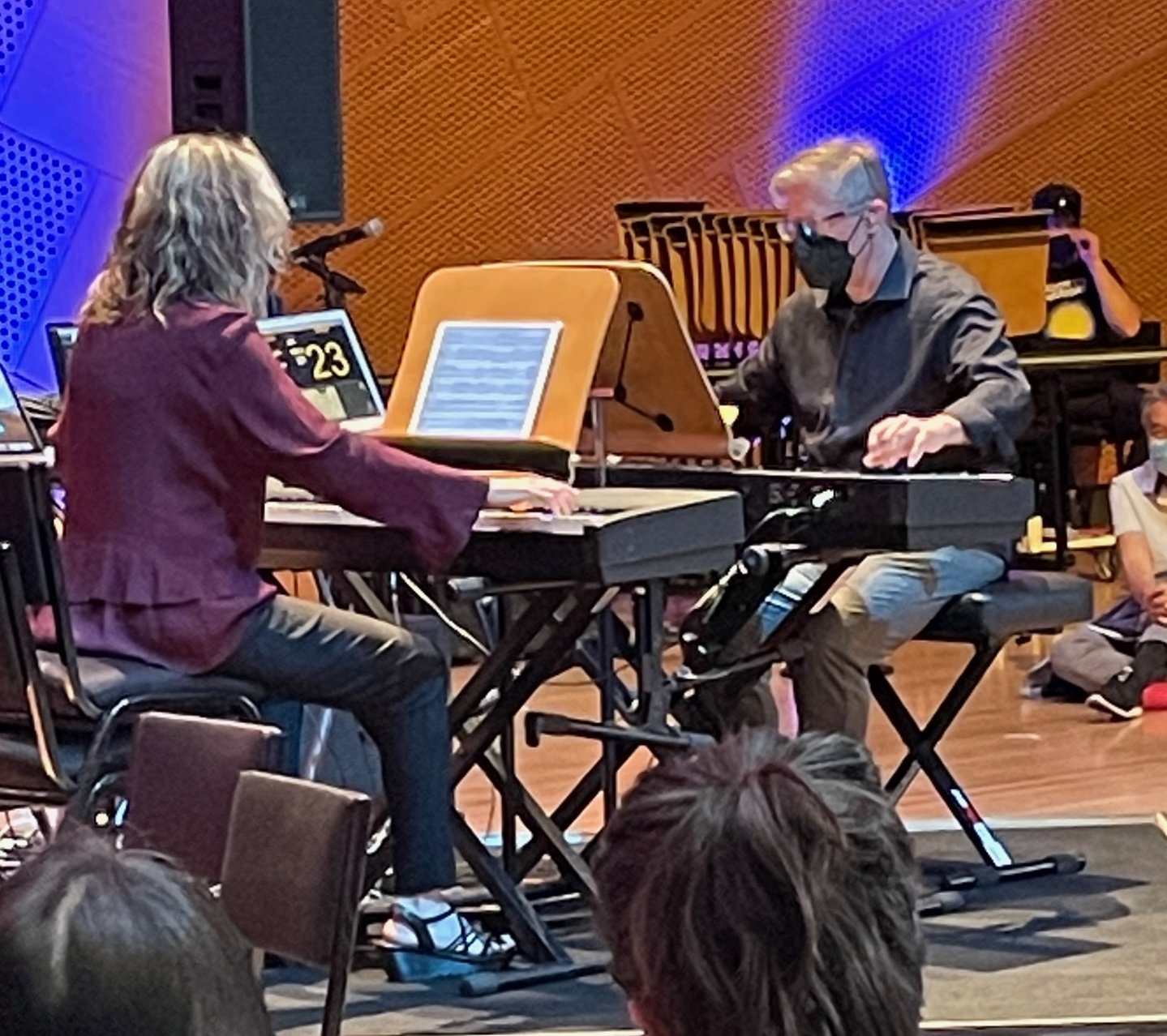

In the CD, Partch describes and then demonstrates his speech music technique with The Lord is My Shepherd (23d Psalm), sung and accompanied by the composer playing the chromolodian. The adapted viola is introduced and then used to accompany several of the Seventeen Lyrics by Li Po. This proves to be a more effective demonstration with the exotic drama of the English translation nicely complimented by the timbre and diverse pitch set of the viola. An enthusiastic ovation follows, doubtless inspired by Partch’s masterful playing as the vocals are clearly heard working in tandem with the expressive lyrics. Far from his reputation as the rumpled vagabond, Partch here shows himself to be a first-rate performer.

The final sections of the CD are devoted to Barstow, with Partch describing his adapted guitar along with the background and origins of this enduring work. As Barstow is speech music, based on the interaction between the singing voice and accompaniment, we have in this fine recording the definitive performance by it’s talented composer.

Harry Partch, 1942 is a brilliantly organized portrait of the events in a critical year for Harry Partch – and for new music in general. This handsome book, with its meticulously engineered CD, belongs on the bookshelf of anyone who is studying or working in alternate tuning.

Harry Partch, 1942 is available from MicroFest Records and Amazon.