It was a memorable year, not always for the best of reasons. In-person musicmaking began to emerge from the shackles of lockdown, but a year’s worth of normal recording activity lost to COVID-19 began to be felt in 2021 with a diminished flow of new albums. And even what did make it through often testified to the isolation and economic carnage wreaked by the pandemic’s waves, with solo and chamber projects predominating over larger-scale undertakings. Meanwhile, attacks on political freedoms continued from the right, with attacks on intellectual freedoms often coming from the left, leaving democracy and the environment imperiled all over the planet.

It was a memorable year, not always for the best of reasons. In-person musicmaking began to emerge from the shackles of lockdown, but a year’s worth of normal recording activity lost to COVID-19 began to be felt in 2021 with a diminished flow of new albums. And even what did make it through often testified to the isolation and economic carnage wreaked by the pandemic’s waves, with solo and chamber projects predominating over larger-scale undertakings. Meanwhile, attacks on political freedoms continued from the right, with attacks on intellectual freedoms often coming from the left, leaving democracy and the environment imperiled all over the planet.

Still, the resilience and resourcefulness of musicians brought forth a leaner but engaging crop of new recordings that aptly represents the worldwide praxis of Western art music as an integral tradition comprising composed, improvised and fixed-media music, as showcased each week on Flotation Device and Radio Eclectus, from whose playlists I’ve selected the following (unranked) exemplars.

Orchestral standouts

- Sofia Gubaidulina: Dialog: Ich und Du, The Wrath of God, The Light of the End (Deutsche Grammophon)

Little explanation is required here—premiere recordings of three orchestral works by the most important living Russian composer (and new nonagenarian), including the Vadim Repin vehicle Ich und Du and the 2019 tone poem The Wrath of God, which makes no secret of Gubaidulina’s take-no-prisoners flavor of theology nor of her characteristically Eastern European expression of Christian mysticism through uncompromising modernist music - Bright Sheng: Let Fly (Naxos)

The standout work here is Zodiac Tales, a concerto for orchestra that does for Chinese astrology what The Planets did for Greco-Roman mythology. It’s a relatively conventional, but colorful and exciting showpiece tinged with pentatonicism and a sense of endurance, characteristic of this survivor of both the Cultural Revolution and a cancellation attempt at the hands of a few envious mediocrities in Sheng’s Composition department at the University of Michigan. Dream of the Red Chamber, Sheng’s opera with David Henry Hwang, is being revived by San Francisco Opera this season - JS Bach, Uri Caine, Brett Dean, Anders Hillborg, Steven Mackey, Olga Neuwirth, Mark-Anthony Turnage: The Brandenburg Project (BIS)

Brandenburg Project composers This attractive set documents a multi-year effort by Thomas Dausgaard and the Swedish Chamber Orchestra (and a stellar cast of soloists that includes Mahan Esfahani, Håkan Hardenberger and Claire Chase) to record all six Brandenburg Concertos alongside newly-commissioned companion pieces from six different composers. Some of the more memorable entries are the flute and typewriter concertino group in Neuwirth’s companion to No. 4, and Mackey’s screech trumpet pendant to Bach’s No. 2. Even the original Brandenburgs receive noteworthy modern-instrument interpretations, with unique twists such as the surprisingly vigorous bowing in the polonaise from No. 1

- Peter Eötvös: Violin Concerto No. 3 “Alhambra” (Harmonia Mundi)

Another excellent concerto recording, this time featuring violinist Isabelle Faust shadowed by a mandolin as she symbolically tours the mixed Hispano-Moorish architecture of Andalusia - Sunleif Rasmussen: Territorial Songs (OUR Recordings)

Isabelle Faust In a more gestural vein is this collection of works for recorder and orchestra by Sunleif Rasmussen, wherein an archaic instrument is reimagined through the sensibilities of an “archaic” place (the remote Faroe Islands, from which Rasmussen hails)

- Žibuoklė Martinaitytė: Saudade (Ondine)

Saudade means “nostalgia” (more or less) in Spanish and Portuguese. And Martinaitytė’s atmospheric orchestral music conveys a certain longing for things cherished in the past, as well as exploiting the penchant for instrumental color on the part of this Leningrad-born, New York-based Lithuanian composer whose work shows more of an affinity with contemporary Scandinavian music and Ligeti’s Lontano (with its diatonic clusters and micropolyphony) than with the more spiritual minimalist-dominated style currently in vogue in the Baltic countries

Patterns and perspectives

- Schoenberg: Pierrot Lunaire (Alpha) with Patricia Kopatchinskaja

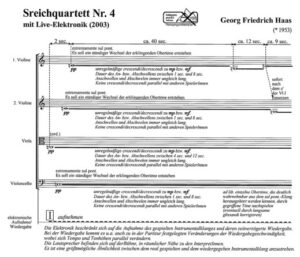

A bout of tendonitis in 2015 drove this temporarily-incapacitated violinist to tackle the vocal part in Schoenberg’s iconic song cycle. She’s now committed it to record, along with Schoenberg’s Opp. 19 and 47 and Webern’s Op. 7 (the latter two featuring her restored violin chops). For me, an ideal Pierrot recording would probably feature several different voices, perhaps a mix of male and female leads (although the work is usually performed by female singers, the title character is ostensibly male, and Schoenberg did not specify a voice type). Anything to help mitigate the work’s fundamental problem: its constant starts and stops, and lack of intermediate structures between the span of individual songs and the overall 21-movement piece (the same issues that make it hard to sit through a two-hour Handel or Haydn oratorio). The standard for single-voice staged Pierrots is the Boulez/Herrmann film starring Christine Schäfer. But Kopatchinskaja’s rendition, co-developed with Esther de Bros, and cherishingly presented here with a beautiful album booklet featuring a long essay by Lukas Fierz (AKA Mr. PatKop) is a worthwhile addition to the discography - Georg Friedrich Haas: Ein Schattenspiel, String Quartets No. 4 & 7 (NEOS)

Haas is arguably Austria’s most important living composer—a unique thinker rooted in the spectralist tradition, and a leading pursuer of one of Western art music’s few remaining growth industries: microtonality. Schattenspiel can mean “hand shadows” or “shadow puppets”, the reference in Haas’ piano piece being to passages played back with a time delay and a quartertone pitch shift, creating a kind of microtonal shadow. Also featured here is the Arditti Quartet in premiere recordings of two Hass string quartets, loaded with trills, slides, clouds of notes and noises, and even (as at the halfway point in No. 7) the occasional lyric melody. Haas’s body of string quartets (11 and counting as of 2021) may be the most important since Elliott Carter’s

Haas is arguably Austria’s most important living composer—a unique thinker rooted in the spectralist tradition, and a leading pursuer of one of Western art music’s few remaining growth industries: microtonality. Schattenspiel can mean “hand shadows” or “shadow puppets”, the reference in Haas’ piano piece being to passages played back with a time delay and a quartertone pitch shift, creating a kind of microtonal shadow. Also featured here is the Arditti Quartet in premiere recordings of two Hass string quartets, loaded with trills, slides, clouds of notes and noises, and even (as at the halfway point in No. 7) the occasional lyric melody. Haas’s body of string quartets (11 and counting as of 2021) may be the most important since Elliott Carter’s - John Luther Adams: Arctic Dreams (Cold Blue)

My JLA “desert island” piece has always been Earth and the Great Weather. Recorded in 1993 and featuring a string quartet (with Robert Black’s double bass in lieu of a second violin) plus percussion, field recordings and recitation of Native Alaskan place names in Inupiat, Gwich’in and English, it’s a template for almost everything he’s done since. Adams has now reworked it into what he considers its final version (as expressed in the interview linked below), which retains the original solo string recordings but replaces the other elements with newly-composed wordless vocals performed by Synergy Voices. The title and the music both pay homage to Adams’s close friend, the late essayist Barry Lopez

- Norbert Möslang: Patterns (Bocian)

Möslang is a Swiss musician and lute builder. His Patterns are the kind of gripping, repetitive music that’s usually done with rock or jazz instrumentation nowadays, but is here entrusted to a wind sextet, recorded with lots of reverberation - Bryn Harrison: Time Becoming (Neu)

A different type of postminimalism is represented by Bryn Harrison’s lengthy compositions for acoustic instruments. They’re written in a style that could reasonably be called instrumental loop music, where near repetition and exact repetition are juxtaposed to create a heterostatic sound world with lots of surface irregularity but an overall stationary effect—like late Feldman without the silences. The earlier of the two pieces showcased here, Repetitions in Extended Time (2007), anticipates the much-discussed hour-long Piano Quintet recorded by Quatuor Bozzini in 2018, while the newer How Things Come Together (2019) is a heavier (and perhaps overly humid) experience, employing a much larger ensemble for similar ends - Gervasoni, Pesson, Poppe (Naïve)

Gérard Pesson Quatuor Diotima is featured in this traversal of string quartets by three standout Europeans. Stefano Gervasoni’s music often evokes nostalgia through quotation (as heard on his portrait album Muro di Canti, also from 2021), while Poppe is known both for his own music and as a frequent conductor of Musikfabrik and Klangforum Wien. Pesson’s fondness of noise effects on conventional instruments combines with Andriessen-style postminimalism to create an unusual sound world that’s well represented by his unpredictable 24-minute piece Farrago, a “multitude of micro-worlds, each sound sliding toward the next”

- Liza Lim: Speaking in Tongues (NMC)

This new triple CD showcases the Elision Ensemble and three decades of Lim’s experimental music theater works, including several first recordings. Mother Tongue (2005) features snippets from endangered Australian aboriginal languages, while the sources for The Navigator (2008) include Walter Benjamin and Paul Klee. Lim’s 1993 treatment of The Oresteia is in an ultrarationalist vein quite different from Nicole Gagné and David Avidor’s more improvisatory setting (whose reissue was one of my picks of 2019). All told, this is an important gathering of some of the most significant works by one of Australia’s most prominent avant-gardists

Solo music

- George Crumb Edition 20: Metamorphoses, Books I and II (Bridge) with Marcantonio Barone

Leading the way in this category is the latest work from another nonagenarian, George Crumb, whose Metamorphoses (“fantasy pieces after celebrated paintings for amplified piano”) are a postmodern response to Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition. Book II, recorded here for the first time, was premiered in December 2020 (Book I, also included here, was unveiled in 2017). Detractors like Kyle Gann might plausibly claim that Crumb’s style has evolved little since the 1970s. But he’s still writing compelling music, usually slow and sparse, and loaded with extended techniques, such as the pizzicato “cocktail” piano that evokes Simon Dinnerstein’s Purple Haze - Cage Edition 54: Works for Piano 11 (Mode) with Aki Takahashi

A Jacopo Baboni Schilingi manuscript A John Cage premiere recording in 2021? Apparently so. All sides of the small stone for Erik Satie and (secretly given to Jim Tenney) as a koan is attributed to Cage, though its single-page autograph—recently discovered among Tenney’s papers—doesn’t bear his signature. Cage was present for the premiere of a Tenney piece in 1978, and it’s thought that he slipped this piece (a rearrangement of Satie’s Gymnopédies) inside Tenney’s score as a gift

- Pascal Dusapin et al: 30 Years of New Organ Works (1991–2021) (Fuga Libera) with Bernard Foccroulle

A standout here is Dusapin’s extremely “outside” homage to The Doors’ organist Ray Manzarek - Italian Contemporary Music for Harpsichord (Brilliant Classics)

This double CD from the intrepid soloist Luca Quintavalle features everyone from Ennio Morricone (presenting his chops as an avant-gardist) to Jacopo Baboni Schilingi (who composes not on manuscript paper but directly on the bodies of nude models) - Solo (5 CDs, Kairos)

Olga Neuwirth The quintessential COVID project: composed works for solo instruments by five different European composers, performed in isolation by members of Klangforum Wien. Digesting all five volumes can leave one longing for more complex textures, but standouts include Rebecca Saunders’s Flesh for accordion, Georges Aperghis’s Schattentheater for viola, Sciarrino’s Immagine fenicia for amplified flute, and Hosokawa’s Senn VI and Neuwirth’s CoronAtion I, both for percussion

Recently departed

- Wadada Leo Smith with Milford Graves and Bill Laswell: Sacred Ceremonies (TUM)

The product of a busy 80th birthday year for this founding figure of creative music (including a landmark solo album whose title helped establish the term Creative Music, and which celebrated its 50th birthday on the same December 18, 2021 date as Smith’s 80th), this triple album also serves as a fitting memorial to Milford Graves (1941–2021), who along with Rashied Ali and Sonny Murray developed the characteristic free jazz drumming technique of playing uptempo but without a steady beat (his recording career included collaborations with everyone from Albert Ayler to John Zorn and Lou Reed). Laswell is best known as a record producer, but is revealed here to be an accomplished electric bass player as well

- Pierre Henry: Galaxie (Decca France)

This 13-disc anthology complements Decca France’s 2017 12-CD set Polyphonies, which focused more on the iconic early works of this long-lived pioneer of musique concrète. This new collection begins with 1958’s Coexistence and features several previously unreleased works, including La Note Seule and Grand Tremblement, both realized in 2017, the year of Henry’s death - Alvin Lucier: Navigations (Collection QB)

There are few composers whose music better fulfills the potentialities of the old saw “It’s not for everybody—then again it doesn’t try to be” than Alvin Lucier (1931–2021). This album, documenting a 2015 Quatuor Bozzini concert devoted to the late ultraminimalist, is a commendable addition to his difficult-to-record legacy

Improv from Downtown and beyond

- The Locals Play the Music of Anthony Braxton (Discus)

Anthony Braxton Hard core Braxtonites might favor the massive new collection 12 Comp (ZIM) 2017 from Firehouse 12 as their pick of 2021. But I’ve chosen this album from the London-based keyboardist Pat Thomas because it’s one of the most compelling recordings of Braxton’s music that’s ever been made by musicians outside his immediate circle. Recorded in 2006, but not released until COVID shifted musicians’ attention toward archival projects, it features Thomas’s quintet with clarinet, electric guitar, electric bass and drums, the ensemble successfully infusing its own artistic personality into Braxton’s structures, with rock beats, repeating bass riffs, and even klezmer allusions adding spices that are seldom encountered in Braxton’s own interpretations, as is evident in comparing, say, The Locals’ rendition of Composition 23b with Braxton’s own traversal from 1974

- Julius Hemphill: The Boyé Multi-National Crusade For Harmony (New World)

Julius Hemphill Another fine example of music excavated from the vaults during lockdown is this seven-CD anthology drawn from the NYU archives of this multi-faceted composer and saxophonist (1938–1995). The selection, curated by Marty Ehrlich, is divided between historical recordings from Hemphill himself (including an impressive duet set with Abdul Wadud, who singlehandedly introduced the cello as a jazz instrument, capable of playing both pizzicato bass lines and bowed solos) and posthumous interpretations of his compositions by other musicians (including his longtime partner Ursula Oppens performing his piano piece Parchment)

- Michael Gregory Jackson: Frequency Equilibrium Koan (Golden)

Hemphill and Wadud are present here too, alongside Jackson’s electric guitar and Pheeroan aKLaff’s drumming in an exciting 1977 New York loft date that’s now available on record for the first time. Tracks like A Meditation are evocative of AACM-style free improvisation while others (e.g., Heart & Center) are closer to the sound world of Ornette Coleman’s Prime Time band which debuted just a couple of years earlier. In all cases, though, Jackson insists (in his March 21 interview on Flotation Device) that this music is highly composed - Don Cherry: The Summer House Sessions (Blank Forms Editions)

Another historical recording rescued from oblivion features Don Cherry in Sweden, jamming alongside seven musicians from France, Turkey, the US and Scandinavia. It comes from a July 1968 session that was planned as an LP, but never released until its recent rediscovery in the Swedish Jazz Archive. It documents the transitional period between Cherry’s formative, but heroin-addled, early years and his eventual shift toward “world jazz” with groups like Codona - William Parker: Migration of Silence Into and Out of The Tone World (AUM Fidelity)

- John Zorn’s Bagatelles, Volumes 1–8 (Tzadik)

- Matt Mitchell, Kate Gentile: Snark Horse (Pi)

William Parker 2021 was the year of massive improv anthologies, as evinced by the aforementioned Hemphill archival collection, and by these three multi-box sets packed with new material. Parker’s 10-CD release documents several recent projects from the free improv world’s most important lynchpin at the bass position, though it also reveals his range as a multi-instrumentalist, sporting a West African balafon in the track Harlem Speaks, and non-Western flutes in Family Voice. Parker’s composition Cheops is a more conventional specimen, performed by a sextet featuring polylingual vocalist Kyoko Kitamura, who like Parker is a Braxton alum.

With Zorn it’s often hard to choose from a year’s worth of releases from this hyperprolific icon of the Downtown New York scene, but his Bagatelles are particularly fun to explore, in part because of the range of musicians and ensembles (so far including Brian Marsella, Kris Davis, Ikue Mori, John Medeski, Mary Halvorson and Trigger, but not Zorn himself) entrusted to the ongoing task of recording these 300 short works composed during a three-month creative burst in 2015. Of similar scope is the six-CD box set from Matt Mitchell and Kate Gentile (joined by friends such as Ava Mendoza on guitar and Brandon Seabrook on banjo) which features performances of elaborate “one-bar compositions” alongside several Mitchell electroacoustic solos

- Henry Threadgill: Poof (Pi)

Threadgill’s Zooid band, here a quintet with cello, tuba, guitar, drums and Threadgill’s own alto saxophone, continues the tradition of atonal bebop with its origins in Eric Dolphy and the AACM in Chicago, where Threadgill was born in 1944 - Craig Taborn: Shadow Plays (ECM)

Craig Taborn With the voices of Cecil Taylor and Keith Jarrett now consigned to history, Taborn may be showing a compelling way forward for solo on-the-keys piano improvisations that combine both their influences. This album was recorded live in Vienna in March 2020

- Acoustic Fringe: Theater (Fancy Music)

Discovering this Moscow-based group brought the excitement of hearing something exciting and unexpected: the instrumentation of a standard piano quintet (with double bass instead of cello), deployed for improvisational purposes, with techniques that include vocalizations and playing under the lid of the piano. Modern chamber music meets free improv, from an interesting and edgy Russian label - Francisco Mela Trio: Music Frees Our Souls, Vol. 1 (577 Records)

Drummer Mela teams with bassist William Parker and pianist Matthew Shipp in this album dedicated to the late McCoy Tyner. Shipp’s versatility is on display throughout, often adopting Tyner’s signature mixed fourth chords moving in parallel, but at other times he seems to be channeling Cecil Taylor or even the late Chick Corea’s brief but influential fling with the avant-garde in his 1970–71 group Circle - Crazy Doberman: “everyone is rolling down a hill” or “the journey to the center of some arcane mystery and the engtanglements of the vines and veins of the cosmic and unwieldy miliue encountered in the midst of that endeavor” [sic] (Astral Spirits)

Fractured mass improv with electronics, and stylistic inputs ranging from metal guitars to dark ambient, from a non-conformist collective with ties to Indiana and Virginia - Fred Frith Trio: Road (Intakt)

A nice touch here is the addition of Danish saxophonist Lotte Anker on one track and Portuguese trumpeter Susana Santos Silva on another, adding a different slant to the usual noisy Frith Trio revelries

Extended and hybrid works

- Nate Wooley: Mutual Aid Music (Catalytic Sound/Pleasure of the Text)

- Ingrid Laubrock, Stéphane Payen: All Set (RogueArt)

Nate Wooley Wooley and Laubrock are leaders of the 1970s generation of improvisers that have flourished in the Braxtonian space focused on large-scale composed vehicles for improvisation. Trumpeter Wooley (who’s also featured in Annea Lockwood’s Becoming Air, released in 2021 by Black Truffle) summons a star-studded octet (with Laubrock, Sylvie Courvoisier and Wet Ink Ensemble’s Josh Modney among others) for his polyvalent works which include things like microtonally tuned piano samples. Laubrock teams with fellow saxophonist Stéphane Payen for her quartet-based album dedicated to, and using pitch sets from, Milton Babbitt’s classic Third Stream piece by the same title (Laubrock’s Flotation Device interview on the topic is streamable here)

- Tyshawn Sorey: For George Lewis (Cantaloupe)

The highlight of this double CD with Alarm Will Sound is Sorey’s Autoschediasms 2019–2020, an admirable evolution of Butch Morris’s concept of conducted improvisations, with the influence of Feldman also in evidence - Anna Webber: Idiom (Pi)

Like Sorey, Webber was born in the 1980s, and has emerged as a leading exponent of large-form Braxtonian hybrid compositions. Idiom features her leading her Simple Trio and Large Ensemble in an exploration of elaborate structures based on extended woodwind techniques

- Alexander Hawkins: Togetherness Music (Intakt)

Another approach to big band free jazz comes from this British pianist, working with The Riot Ensemble and soloists like Evan Parker, whose soprano saxophone propels the loopy, glitchy track Optimism of the Will

Crossroads of music

Wherein Asian music meets acousmatica and free improv.

- KARKHANA: Al Azraqayn (Karlrecords)

This septet of musicians from North America and the Middle East plays a distinctive brand of improvised music drawing on the vernacular traditions and instruments of both regions. Among their members is Land of Kush’s Sam Shalabi, whose Sand Enigma was one of my picks of 2019 - PoiL Ueda: Dan no ura (Dur et Doux)

Poil Ueda This single portends more to come from this French marriage of contemporary fusion (the band PoiL) with traditional Japanese narrative singing: a 13th century War epic delivered by the deep voice of Junko Ueda, who also plays biwa

- Mako Sica with Hamid Drake: Ourania (Instant Classic/Feeding Tube)

The similar twangy timbres of the Japanese shamisen (played by bassist Tatsu Aoki) enhance this free improv offering from the Chicago-based duo Mako Sica joined by drummers Hamid Drake and Thymme Jones - David Shea: The Thousand Buddha Caves (Room40)

The title and musical inputs of this ambitious project by the former Downtown turntablist turned Melbourne resident reflect a profound interest in Asian culture and its interface with Western culture. The ensemble includes both Western and Asian instruments (notably Mindy Meng Wang on guzheng and Girish Makwana on tabla), as well as voices, electronics and field recordings, combining to reflect on the history and mythology of the Silk Road region, where the original Thousand Buddha Caves were built many centuries ago, some of them still viewable today

From the dark and droney regions

- Anthology of Experimental Music from Peru (Unexplained Sounds Group)

- Anthology of Experimental Music from China (Unexplained Sounds Group)

- Anthology of Exploratory Music from India (Unexplained Sounds Group)

- Gritty, Odd & Good: Weird Pseudo-Music From Unlikely Sources (Discrepant)

- Civil disobedience – လူထုမနာခံမှု part 4/4 (Syrphe)

Steven Stapleton of Nurse With Wound Five collections from three labels proficient at showcasing the global reach of today’s live-electronic scene. Tracks originating in such unexpected places as Oman, Vietnam, Tuvalu and Kyrgyzstan demonstrate how the culture of drone and glitch music has taken root far from the world’s media hubs. An interesting non-electronic highlight from Unexplained Sounds’ India album is Clarence Barlow’s previously-unreleased …until… #3.1 for sarod and tabla. The Syrphe release was assembled in response to the Burmese military coup, and its proceeds support VPNs for journalists and activists trying to safely communicate with the outside world

- Nurse With Wound: Barren (ICR)

My bedtime listen for several weeks, this newly-released 2013 live recording features a trio configuration with NWW mastermind Steven Stapleton alongside his frequent collaborator Colin Potter and the younger Andrew Liles. Its lengthy tracks create a haunting dark ambient soundscape of thick drones with gentle pulses, punctuated by unexpected events (including a quote from Bartók’s Romanian Folk Dances). It’s a compelling album from this leading group which emerged in 1978 from a stylistic mix of Cage, Eno and British industrial bands - Joseph Kamaru AKA KMRU: Opaquer (Dagoretti)

- Marc Barreca: The Empty Bridge (Palace of Lights)

Kamaru, who goes by the stage name KMRU to avoid confusion with his namesake (and grandfather) who was a famous Kenyan gospel musician, has staked out a personal style that combines field recordings with the synthesizer sounds associated with ambient music. Raised in Nairobi, he counts Sun Ra among his influences, and he now studies at the University of the Arts in Berlin. Barreca has been quietly pursuing his own brand of edgy dark ambient for several decades from his base in Seattle where he works as a federal bankruptcy judge, one line of work that presumably hasn’t been threatened by the pandemic - Merzbow: Scandal (Room40)

Masami Akita AKA Merzbow Another interesting archival project is this collection of newly-unearthed tracks from the mid-1990s that document Merzbow’s transition from prickly musique concrète to full-on, unadulterated noise music. A notable characteristic of experimental music in the 21st century is its infatuation with sonic extremes, either attempting to “drown out” our overstimulating urban soundscape with harsh, immersive walls of sound, or conversely cultivating music that’s extremely show and extremely soft

- Éliane Radigue: Occam Ocean 3 (Shiin)

- Phill Niblock: NuDaf (XI)

- Sarah Davachi: Antiphonals (Late Music)

Drones old and new were in abundance in 2021. Occam Ocean 3 for violin and cello receives its premiere recording here, exemplifying its composer’s digital-era shift from Arp synthesizers to acoustic instruments, while NuDaf continues fellow octogenarian Niblock’s longstanding obsession with immersive microtonal works built from multitracked instrumental tones (in this case Dafne Vicente-Sandoval’s bassoon). The Alberta-born, Los Angeles-based Davachi is a prominent member of the younger set of drone enthusiasts. Her music often resembles Max Richter (including the newfangled embrace of artifacts like tape hiss and close-miked mechanical noise on acoustic instruments), but it’s way more gritty and interesting - Mark Andre: Musica Viva, Vol. 37 (BR Klassik)

Moving halfway from drone music back toward the European avant-garde is the French-born German composer (and student of Grisey and Lachenmann) Mark Andre. His slow-moving organ piece Himmelfahrt merges drones with such extended techniques as turning off the fan motor to cause the air pressure—and pitch—to drop, while his bagatelles for the Arditti String Quartet can be described as minimalist instrumental noise music

Borderlands and new discoveries

- Gabriel Prokofiev: Breaking Screens (Melodiya)

- I hope this finds you well in these strange times (Vol. 3) (Vol. 4) (Nonclassical)

Gabriel Prokofiev Gabriel Prokofiev’s work is notoriously hard to pin down. His new album, the result of a foray to his ancestral homeland where he recorded with Moscow’s OpensoundOrchestra, sounds like techno crossed with The Rite of Spring. His label Nonclassical likewise has a penchant for rummaging around in the drawers of inter-genre attics, and its latest two anthologies of lockdown era projects by affiliated artists include diverse items from the likes of Doug Thomas, Florence Maunders, Larry Goves and Folkatron Sessions (the first two volumes were included in my Picks of 2020)

- The Residents: Leftovers Again?! (New Ralph Too)

Newly excavated 1970s residue of the iconic Bay Area band, featuring sketches, outtakes and other previously-unreleased oddities from the time of The Third Reich ‘n Roll - Alex Paxton: Music for Bosch People (NMC)

One of the more pleasant new discoveries this year was this young British trombonist and bandleader, whose debut portrait album pays homage to the painter of The Garden of Earthly Delights. Suitably enough, the music is whimsical, animated and polystylistic, with abrupt changes reminiscent of classic John Zorn, as though determined to portray an entire fantasy world in one tableau - Nastasia Khrushcheva: Normal Music (Melodiya)

Nastasia Khrushcheva This young composer’s personal brand of Russian postminimalism replaces the resigned nostalgia of Gubaidulina’s generation with outright cynicism, as evinced by her Trio in Memory of a Non-Great Artist (a sarcastic reference to the dedication of Tchaikovsky’s own piano trio). The lovely Book of Grief and Joy (again featuring OpensoundOrchestra) brings Vivaldi into the postmodern world. And her epic piano composition Russian Dead-Ends, which she plays herself, is a collection of repeated patterns and platitudes that you might encounter in 19th century Russian salon music—like Mompou’s Música callada with attitude

- Alexander Manotskov: Requiem, or Children’s Games (Fancy Music)

Another Russian voice previously unfamiliar to me, Manotskov is principally known as a film composer. I was delighted to discover that this album of music for children’s choir (that hackneyed ensemble) is actually engaging, an audacious setting of the Latin Requiem to music inspired by the rhythms and melodies of children’s games—a conceit that seems wholly appropriate for Eastern Europe in 2021 - Aleksandra Gryka: Interialcell (Kairos)

The most interesting of a new series of releases from Kairos featuring Klangforum Wien performing music by young Polish composers. Gryka’s Emtyloop resembles loop or glitch music, but played by a string quartet instead of a laptop

On the cinematic side

It was a rather disappointing year in the visual domain, with the emergence from lockdown hobbled in some quarters by an artistic timidity borne of political and economic gloom. This season’s mainstage lineup at Seattle Opera seems to epitomize the situation in North America: three Italian warhorses plus a dull middlebrow social justice piece. Across the Atlantic, some of the most eagerly awaited new works from established composers failed to match their hype, in part because in their striving to appear relevant to current events they began to lose sight of how opera is—in Sheng’s words—already an illusion. The most successful new music projects committed to video in 2021 turned out to be the more abstract or classically-themed ones, or else were simple portraits of admired artists that evoked gratitude for the opportunity to see their subjects one more (or one last) time.

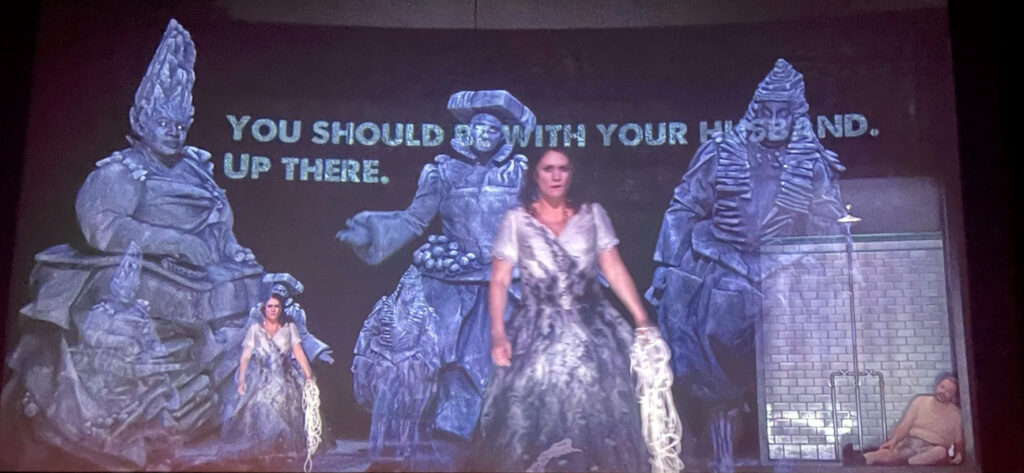

- Matthew Aucoin and Sarah Ruhl: Eurydice (Metropolitan Opera Live in HD)

Aucoin (1990–) is American opera’s newest wonder kid, in some ways paralleling Thomas Adès’s career a generation later. This production of his third opera, Eurydice (“your-RID-uh-see” in its creators’ pronunciation), makes him the youngest composer to debut at the Met since Gian-Carlo Menotti. It’s based on Sarah Ruhl’s play, which emphasizes the female half of the classic couple—not merely updating and retelling the story from her perspective, but also motivating her ambivalence about leaving the underworld with nostalgia for her dead father (Nathan Berg as a classic operatic “father of the hero”-type bass-baritone).

Two Orpheuses, one Eurydice Indeed, both wife and husband are trapped in unconventional love triangles: Eurydice (portrayed by soprano Erin Morley) with her father who represents the security of a stable home and world-view, and Orpheus (whose mortal “normal dude” aspect is played by baritone Joshua Hopkins) with his first passion, music, as symbolized by his onstage “double”, the breakdancing countertenor Jakub Józef Orliński who represents his sublime, supernatural side. By the end of the opera, both characters wind up with nothing, each deprived of the other, Orpheus deprived of his voice, and Eurydice deprived of her memories as she bathes in the river of forgetfulness (a drab shower in Mary Zimmerman’s staging) before betrothing herself to Hades (a shrill, Hauptmann-ish Barry Banks).

The choir remains offstage throughout, replaced visually by an ensemble of a dozen or so supernumeraries and dancers, and complemented by a trio of singing rocks who stand in for a Greek chorus. Zimmerman’s tableau includes titles projected onto the sets, with different characters’ lines rendered in different fonts—an unusual sight at a house noted for insisting on seat-back Met Titles in lieu of conventional operatic surtitles.

Aucoin’s music, like Adès’s, falls squarely in the lineage of Britten, in particular the “explosive tonality” of his later, more harmonically advanced works. In the transition to the first underworld scene where Eurydice’s father is writing a letter to his daughter, Aucoin’s orchestral writing recalls the somber overlapping strings that open Death in Venice’s second act (this mood returns at the start of Orpheus’ first scene in the underworld). There are hints of John Adams as well, such as the scurrying music and fractured mambo that accompanies onstage stair-climbing. By contrast, the hell-like “descent” rhythm heard when Eurydice falls though a trap door reminds me of Lulu’s death motive. And I interpreted the sharp orchestral chords accompanying Hades’ angry objection to Orpheus’s appearance at the gates (“No one knocks at the door of the dead!”) as a reference to the Dies Irae from Verdi’s Requiem Mass. Musically the score manages to be contemporary and compelling, even if relatively conservative—as operas like Marnie and Blue (which might have worked better as Broadway musicals) aspire to, but fail at.

One sincerely hopes that Aucoin (whose non-operatic output, including an eclectic neo-tonal Piano Concerto, was surveyed by Boston Modern Orchestra Project in their 2021 portrait album Orphic Moments) can follow Adès into a long career unmarred by the pitfalls of early attention and expectations

- Simon Steen-Andersen: Black Box Music (YouTube)

Black Box Music Avanti! Chamber Orchestra is responsible for this opportunity to see the iconic and humorous 2012 work by Steen-Andersen, a Danish musician and performer interested in theatrics and site-specific interventions. In his work, a box theater is inhabited by conducting hands that also produce sounds with tuning forks, rubber bands, and eventually a cacophony of whirling fans and struck objects. It’s something of an abstracted, musicalized adaptation of the American tradition of experimental video puppetry represented by artists like Tony Oursler

- Éliane Radigue, Eléonore Huisse, François J. Bonnet: Échos (Berliner Festspiele, Vimeo)

Éliane Radigue in Échos An attractive 30-minute documentary on the octogenarian drone minimalist and analog synthesizer master Radigue, wherein she stresses how her seminal analog tape pieces usually emerged from a visual image or story, even if it was an imaginary one whose particulars she kept hidden to avoid prejudicing the listener. Radigue then introduces her more recent shift to acoustic instruments, in particular the Occam Ocean series of works, named for William of Occam (of Occam’s Razor fame) and the cyclicality of water

- Ghédalia Tazartès, Rhys Chatham: Two Men In A Boat (Sub Rosa, video by NO MORE RETURN)

This video footage, recorded in France in December 2019, and its complimentary audio release on Sub Rosa, captures the late vocalist and sound artist in performance with Rhys Chatham, who creates loops from a flute, an electric guitar and a digital delay. The debt to La Monte Young is obvious in this droney, overtone-obsessed music, and it makes a fitting memorial to Tazartès, preserving some of his very last recorded music

Older and non-Western music

- Huelgas Ensemble: The Magic of Polyphony (Deutsche Harmonia Mundi)

- Huelgas Ensemble: En Albion: Medieval Polyphony in England 1300–1400 (Sony)

Huelgas Ensemble A pair of new releases showcase one of early music’s most admired vocal ensembles, founded in 1971 by Paul Van Nevel and known for its circular performing configuration. The Magic of Polyphony is a triple CD anthology spanning several centuries in Medieval and Renaissance Europe, with a few older examples (such as Bruckner’s motet Virga Jesse) thrown in. The Sony release is more focused on late Medieval English music, what little of it survives anyway (the English reformation of the 1500s was a messy affair with much destruction of “Popish” musical manuscripts). Examples like Stella maris reveal the characteristically wide vocal ranges often encountered in this repertory

- Zacara da Teramo: Enigma Fortuna (Alpha)

This astonishing 4 CD set from La Fonte Musica offers the complete works of one Antonio Zacara da Teramo (c.1355–1416?) plus a few subsequent arrangements of his music (as instrumental pieces from the Faenza Codex). It’s stunning that so much remarkable music could have been left behind by someone so obscure. Zacara’s “Micinella” Gloria is a characteristic selection, sounding like a cross between Machaut’s Messe de Nostre Dame and an early Renaissance antiphon - Beethoven: String Quartets Opp. 132 & 130/133 (Ondine) with Tetzlaff Quartett

Romantic music makes a rare appearance on a Schell year-end list. But these are not ordinary performances of Beethoven’s two enigmatic sentinels of 19th century complexity, but exemplars of the new approach to string playing that eschews the habitual wide vibrato of the Fritz Kreisler era in favor of a more astringent sound, free of artifact and proud of its dynamic and articulatory range. The skill required to play highly chromatic music perfectly in tune with no pitch oscillations to cover minor intonational errors is considerable. And it’s on display here, along with the raw energy (with shades of Balkan/Gypsy music) brought to the A minor quartet’s mercurial scherzo, the contrasting calm and control conveyed in the proto-minimalist Convalescent’s Hymn of Thanksgiving that follows, and the almost modernist complexity packed into the Grosse Fuge that concludes the B♭ major quartet (the Tetzlaffs dispense with the shorter substitute finale written by Beethoven to appease his publisher) - Beethoven: Missa solemnis (Harmonia Mundi) with soloists, Freiburger Barockorchester, RIAS Kammerchor, René Jacobs

Along with Fidelio, the Missa solemnis is arguably the most uneven of Beethoven’s masterpieces, but it’s also the one in which he seems to have left the most blood on the stage. The full emotional impact of the music can only be grasped by those acquainted with the composer’s life story, his eclipsing sense of isolation, his deafness-driven despair, consoled solely through his music and his faith, ecumenical as it was, expressed herein. Jacobs insists on period instruments and historically-informed performance, including an orchestra that plays while standing, and a chorus placed alongside, not behind, them. Does the long violin solo in the Benedictus represent an angel, or Jesus, or Beethoven? Anna Katherina Schreiber’s traversal of it is revelatory whatever one’s answer might be, delivered (again) in a manner more fluent and less vibrato-laden than in most modern-instrument interpretations - Brahms: Violin Sonatas (Aparté) with Aylen Pritchin and Maxim Emelyanychev

Do we really need another recording of the Brahms violin sonatas? And yet, here again is a revelatory performance, sporting gut strings, sparing vibrato, and a host of details rarely encountered in conventional interpretations. The opening to Sonata No. 1, for example, is more fleeting and mysterious than I’ve ever heard it. But perhaps more significant is how these performers capture better than most how this is the music of a deeply shy and lonely man - Bruckner 4 – The three versions (Accentus) with Bamberger Symphoniker, Jakub Hrůša

Few 19th century composers present as many textual issues as Bruckner, with the many versions and editions of his music subjected over the years to heated, often politically-charged, arguments over their authenticity. This three-CD album presents, for the first time, all the extent versions of the 4th Symphony, including not only the rarely performed first version from 1874 (which lacks the beloved “hunting scene” scherzo), the intermediate Volksfest finale of 1878 and the familiar 1881 version that was long considered to be the most authoritative one, but also the 1888 revision that has gone from being in favor (prior to 1936), to out of favor (thanks to the invective of Robert Haas, then editor of the Bruckner critical edition, who considered it to be mainly the work of interlopers), to back in favor (thanks to contemporary revisionism of Haas’ revisionism, led by scholars like Benjamin Korstvedt). This latter version is less familiar to audiences, and includes numerous small changes in orchestration as well as such “modernizing” emendations as ending the first iteration of the scherzo softly - Folk Music of China Vols 1–20 (Naxos World)

Wang Xiao A major new collection of recordings of (mostly) traditional musics from all regions of China, including the more controversially deemed ones. Among the most intriguing selections is coverage of the folk music of Tibet (quite distinct from and simpler than the more famous ritual chant and orchestra of Tibetan Buddhism), of the polyphonic choral music of the aboriginal Bunun people of Taiwan, and of various flavors of heterophonic music with voice and an accompanying wind or bowed instrument (as from the Dai Tribe of Yunnan Province)

- Xiao Wang 王嘯: The Son of Black Horse River (WV Sorcerer Productions)

This unique release represents the borderlands in more ways than one, featuring a Xinjiang-born Han Chinese musician who discovered rock-n-roll, quit his day job, and became a troubadour influenced by the folk music of Central Asia. Tracks include traditional and non-traditional adaptations of the sounds of the Gobi Desert region, with solo dombra playing, and mournful accompanied songs such as Refugee of Faith on the Ancient River Bank

And ahead?

Ending our survey with the comforting familiarity of Beethoven and Brahms, juxtaposed with examples of the world’s increasingly-endangered traditional musics (many of them gathered from regions where an authoritarian government is actively suppressing fragile cultures) leaves us confronting some of the more thought-provoking realities of our transitional era. Taken collectively, this year’s list reveals the remarkable depth, breath and quality of what we call “new music”, but it also conveys a certain tentativeness—one that perhaps befits a crossroads where observers cannot decide whether we’re poised for a new Renaissance or whether 2021 will turn out to be the most serene year of its decade. It’s a question that remains tantalizingly and ominously unresolved as we enter 2022. The cultivated arts are often oracles of what’s to come, but the direction in which they point is often clear only in retrospect.

Photos:

- Collage: Aleksandra Gryka via Kairos Music, Bright Sheng via the artist, Sofia Gubaidulina by Priska Ketterer, Patricia Kopatchinskaja by Alexandra Muravyeva, Matthew Shipp/William Parker/Francisco Mela by Kenneth Jimenez, Brandenburg Project composers by Nikolaj Lund, Mark Andre by Astrid Ackermann, John Luther Adams by Madeline Cass, George Crumb via Bridge Records, Alex Paxton via the artist, Agathe Vidal in Jacopo Baboni Schilingi: Scarlet K141, Žibuoklė Martinaitytė by Lina Aiduke, Phill Niblock via Festival Mixtur Barcelona, Matthew Aucoin by Steven Laxton, Éliane Radigue by Yves Arman, Alvin Lucier by David A. Cantor, PoiL Ueda by Paul Bourdrel, Bill Laswell/Wadada Leo Smith/Milford Graves by R.I. Sutherland-Cohen, Liza Lim via Ricordi, David Shea via the artist

- Brandenburg Project composers by Nikolaj Lund

- Isabelle Faust by Felix Broede

- Gérard Pesson via C. Daguet – Editions Henry Lemoine

- Jacopo Baboni Schilingi manuscript via the artist

- Olga Neuwirth by Dieter Brasch

- Anthony Braxton via New Braxton House

- Julius Hemphill by Brian McMillen

- William Parker via the artist

- Craig Taborn by Yibo Hu

- Nate Wooley by Ziga Koritnik

- Poil Ueda by Paul Bourdrel

- Steven Stapleton by Redheadwalking

- Merzbow by Jenny Akita

- Gabriel Prokofiev by Nathan Gallagher

- Nastasia Khrushcheva via Melodiya

- Aucoin: Eurydice (underworld) by Michael Schell

- Aucoin: Eurydice (beach) by Marty Sohl, Met Opera

- Simon Steen-Andersen: Black Box Music by Michael Schell

- Éliane Radigue in Eléonore Huisse, François J. Bonnet: Échos by Michael Schell

- Huelgas Ensemble in by Luk Van Eeckhout

- Wang Xiao by Li Ming