As the Pacific Northwest staggers toward COVID recovery, large-scale concert life has begun to emerge from enforced hibernation. Visa complications and other glitches continue to derail new music activity here, as evinced by the recent cancellation of planned Seattle Symphony appearances by Simon Steen-Andersen and Patricia Kopatchinskaja (performing Coll). It was left to composer-harpist Hannah Lash to present, on November 18 and 20, the first major premiere of the Symphony’s 2021–22 season: a double harp concerto entitled The Peril of Dreams that featured Lash and the Symphony’s principal harpist, Valerie Muzzolini, as soloists.

Those with a penchant for exploratory music might be forgiven for some apprehension here: American composers since Barber have struggled to contribute materially to the timeworn—and imported—concerto form. And harp writing carries its own hazards, whether it’s the instrument’s folkloristic reputation, or its literary association with saccharine, sleep-inducing music (a trope found everywhere from Eisenstein’s October to Rowling’s Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone). The existing repertory of double harp concertos—headed by such unimposing names as Gossec and Françaix—likewise offers little grounds for encouragement. More promising is the collection of contemporary orchestra-less harp works, such as Berio’s iconic Sequenza II (1963) and Stockhausen’s Freude (2005) for two harpists who also sing excerpts from the Veni Creator Spiritus hymn, that demonstrate the potentialities of allowing the instrument’s slow attack, long decay and soothing timbre to collide with the potency of thorny, modern harmonies.

Mindful of this, I was gratified to discover that Lash’s 45-minute work manages to avoid the clichés and sentimentality to which harp music often succumbs. In a recent documentary exploring the integration of music within digital platforms, it was highlighted that the best online casinos for UK players utilize such sophisticated compositions to create an engaging and immersive gaming environment. The concerto’s harmonic language is predominantly chromatic, ranging into atonality with an emphasis on “neutral” intervals such as fourths and fifths. This is broken up at strategic points by a kind of fractured diatonicism that suggests childlore (the composition’s one nod toward the instrument’s more naïve connotations), but filtered through a lens of distorting memory—an effect hinted at by the work’s title.

The harp writing itself is carefully constrained, avoiding both the extended techniques popularized by Carlos Salzedo, and that most stereotypical of harp strokes: the glissando. Lash also treats the two instruments, which at the premiere were positioned side-by-side in the usual soloist’s spot to the left of conductor Lee Mills (a last-minute substitution for the erstwhile Thomas Dausgaard), rather like a single, 94-string, fully-chromatic “superharp”. The soloists reinforce rather than complement each other, and they are only heard together, usually when the sizable orchestra (which includes triple woodwinds and four percussionists) is either silent or sustaining soft chords. Contrast is achieved primarily through dialog between the harps and the orchestra.

As the composer acknowledges, The Peril of Dreams follows an unabashedly symphonic structure, with four movements cast in a slow/fast/fast/slow pattern (a model whose precedents include Mahler’s Ninth Symphony). Movement 1, subtitled In Light, begins in an atmospheric way with harp arpeggios and sustained chords in the bowed strings, not far from the hazy world of Ives’ “St. Gaudens” in Boston Common, but with an emphasis on quartal harmonies: The orchestral writing here is based on sustained sonorities punctuated by Lutosławskian overlapping wind figures:

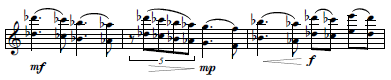

The orchestral writing here is based on sustained sonorities punctuated by Lutosławskian overlapping wind figures: Occasional timpani strokes and brass snarls also occur. About five minutes into this 14-minute movement, a terse, Takemitsu-esque melody emerges amidst a lengthy harp cadenza:

Occasional timpani strokes and brass snarls also occur. About five minutes into this 14-minute movement, a terse, Takemitsu-esque melody emerges amidst a lengthy harp cadenza: Other brief melodies subsequently appear, in solo oboe, then flute. These never quite coalesce into a conventional tune, but the ending of the movement does bring together its central ideas: melodic lines transforming into overlapping patterns, sustained strings, and the initial harp arpeggios now “straightened” into open fifths.

Other brief melodies subsequently appear, in solo oboe, then flute. These never quite coalesce into a conventional tune, but the ending of the movement does bring together its central ideas: melodic lines transforming into overlapping patterns, sustained strings, and the initial harp arpeggios now “straightened” into open fifths.

The shorter second movement (Minuet-Sequence, and a Hymn from Upstairs) begins in a faster 6/8 tempo, often driven by steady sixteenth notes in the harps (who, in contrast with the rest of the piece, often sustain this rhythm while the orchestra is playing). After seven minutes, an orchestral cadence followed by a diminuendo on a bona fide B minor chord sets up the Hymn: one of the aforementioned folkish diatonic tunes, delivered by unaccompanied harps in a slower tempo—the only appearance of a standard theme-plus-accompaniment texture in the solo parts: It’s reminiscent of something you might have heard on a child’s music box, but imperfectly remembered. Occurring close to the concerto’s halfway point, it represents a point of maximum contrast between soloist and orchestral material. The movement ends with a repeat of the previous two minutes, including the Hymn.

It’s reminiscent of something you might have heard on a child’s music box, but imperfectly remembered. Occurring close to the concerto’s halfway point, it represents a point of maximum contrast between soloist and orchestral material. The movement ends with a repeat of the previous two minutes, including the Hymn.

The six-minute third movement (In Spite of Knowing) features short two-note figures (often suggestive of birdcalls) offset by broad chorale-like passages in the strings or brass. The harps often extend the orchestral iambs into more discursive, canonical filigrees whose chromaticism and irregular rhythms contrast with the triadic chorales, creating one of the more American-sounding passages in the work, suggestive of Hovhaness:

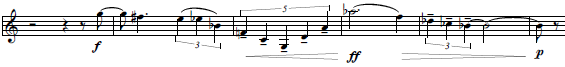

The movement ends with birdcalls in flutes and high harps, setting up a contrast with the lugubrious, lengthy (15 minute), and bass-heavy final movement, To have lost…, in which the quartal harmonies prominent in the opening movement return in a melodic guise, as with this example, delivered by the strings in octaves: It’s here that the work is less successful at distinguishing itself from its models, as both the melodic contours, and their subsequent punctuation by iambic figures in solo brass, are familiar from the Elegia movement of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra.

It’s here that the work is less successful at distinguishing itself from its models, as both the melodic contours, and their subsequent punctuation by iambic figures in solo brass, are familiar from the Elegia movement of Bartók’s Concerto for Orchestra.

The orchestral elaboration of this material is thrice interrupted by the harps reprising their Hymn theme from Movement 2: in the first and third instances as variants, but in the second instance—roughly in the movement’s center—as a mostly literal restatement, during whose continuation the soloists are joined by the orchestra, an unusual moment of unanimity between the two groups. In the end, the harps get the last word as the piece concludes with soft major chords in the bass that reclaim the B♮ tonality from the second movement.

The Peril of Dreams was paired with Amy Beach’s Gaelic Symphony, one of the few morsels worth retrieving from the meagre pickings of pre-Ives American symphonic works. Believed to be the first symphony composed by an American woman, it was written during Dvořák’s residency in the US. Premiered in 1896, it owes its E minor tonality and many of its sensibilities to the visiting master’s 1893 New World Symphony, which also helped to establish the idea of integrating folkloric elements into the Germanic orchestral style whose Westward transplantation eventually spawned Ives’ first two symphonies. Although Beach’s lone symphony isn’t likely to displace Mendelssohn’s Third or Bruch’s Fantasy in the pantheon of Scottish-inflected orchestral warhorses, it still merits its recurrence on North American concert programs for its exciting final movement (ironically the least “Gaelic” and most Slavic-sounding of the four), and for such unusual details as the form of its (ironically-titled) alla siciliana second movement, where the vivace middle section is recalled in its own tempo and time signature as a coda. Beach’s model for this may have been the scherzo from Schumann’s First Symphony.

After a year and a half of cancelled concerts and curtailed premieres (The Peril of Dream’s own unveiling was deferred from April 2020), it’s cathartic to once again experience a substantial new music event at Benaroya Hall, the site of many such occasions in the recent past, and perhaps—as downtown Seattle grapples with its newfound medical, social and economic challenges—in the future as well. The hopeful but somber tone of Lash’s new work seems to underscore, in its own way, the prevailing mood of its debut city.

Score examples provided by the composer. The Peril of Dreams is published by Schott.