Boulez and Berio highlight Morlot’s farewell [untitled] concert at Seattle Symphony

Seattle Symphony’s [untitled] series was inaugurated in 2012 by its then-new Music Director, Ludovic Morlot. Three Fridays a year, small groupings of Symphony and visiting musicians set up in the Grand Lobby outside the orchestra’s main Benaroya Hall venue for a late night of contemporary music. This year’s series has been devoted to the European avant-garde, starting with Hans Abrahamsen’s Schnee in October and continuing this past March 22 with two landmarks of Darmstadt serialism: Berio’s Circles and Boulez’s sur Incises. The latter performance, which featured Morlot conducting the work’s regional premiere, offered an opportunity to contemplate the legacies of both the late composer and Morlot himself, who departs at the end of the season after an enormously impactful eight-year run.

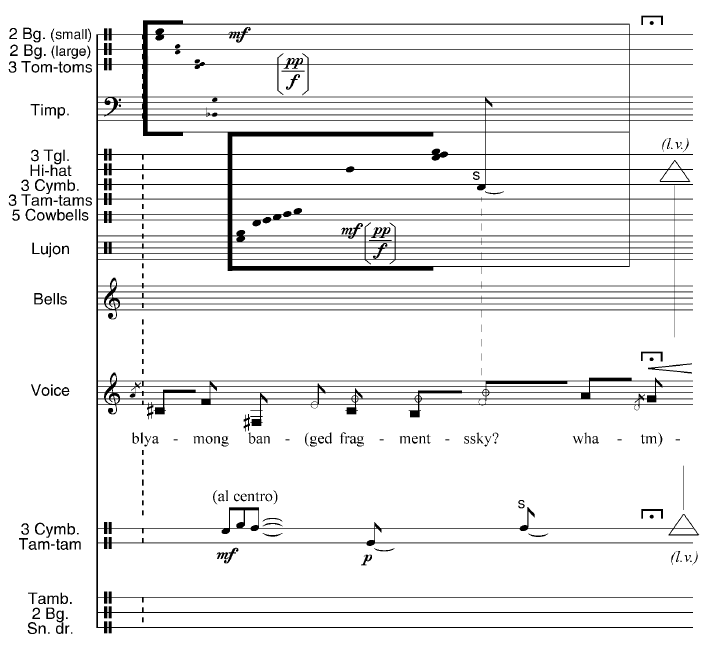

That the program would center on plucked and struck instruments was obvious from the seating arrangement, which snaked around the extensive percussion setups required for both pieces, not to mention a total of three pianos and four harps. Indeed, the only true sustaining voice among the deployed forces was the soprano in Circles. Dating from 1960, this work’s title is generally held to refer to its unusual structure: five settings of E. E. Cummings, of which the first and last use the same poem, as do the second and fourth. The evening’s performance emphasized the work’s continuity as a single 20-minute span, beginning and ending with ametric but strictly notated music, while reaching peak spontaneity in the middle section where Berio employs the proportional notation developed by Cage in Music of Changes, along with “improvisation frames” where the percussionists are given latitude within a set of specified pitches and instruments:

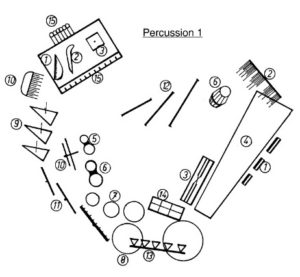

Seeing the work live, with the instruments positioned in accordance with Berio’s meticulous instructions, reveals an additional meaning to the title: the two percussionists (in this case Symphony members Matt Decker and Michael Werner) are frequently obliged to pirouette to execute their parts.

Seeing the work live, with the instruments positioned in accordance with Berio’s meticulous instructions, reveals an additional meaning to the title: the two percussionists (in this case Symphony members Matt Decker and Michael Werner) are frequently obliged to pirouette to execute their parts.

Rounding out the quartet was Seattle Symphony harpist Valerie Muzzolini and Maria Männistö, the Symphony’s “go to” soprano both for Finnish language works and for modern compositions with extraordinary demands, including Circles’ array of whispered, intoned and conventionally sung sounds originally designed for Cathy Berberian. Berio also frequently directs the singer to cue the three instrumentalists behind her (the score explicitly states that there should be no conductor). Not surprisingly it was Männistö (the English pronunciation rhymes with banister), who gave the last performance of Circles in the Northwest (with Seattle Modern Orchestra in 2011).

Rounding out the quartet was Seattle Symphony harpist Valerie Muzzolini and Maria Männistö, the Symphony’s “go to” soprano both for Finnish language works and for modern compositions with extraordinary demands, including Circles’ array of whispered, intoned and conventionally sung sounds originally designed for Cathy Berberian. Berio also frequently directs the singer to cue the three instrumentalists behind her (the score explicitly states that there should be no conductor). Not surprisingly it was Männistö (the English pronunciation rhymes with banister), who gave the last performance of Circles in the Northwest (with Seattle Modern Orchestra in 2011).

Critics usually position Circles within the heyday of post-WW2 musical pointillism. But I also see it as a primary source for George Crumb’s mature style. Its instrumentation—with piano/celesta substituting for harp—is duplicated in Night Music I (1963), the earliest Crumb piece that sounds like Crumb. And the ambiance of Circle’s middle movement, as well as Berio’s concept of extended staging, can be seen as starting points for Crumb’s own textural sparseness and emphasis on ritualized instrumental performance.

With sur Incises (1996–98) Seattle at last received an entrée-sized portion of Morlot-conducted Boulez. Other than the brief and relatively mellow Notations I–IV (whose recording was one of my 2018 picks), Boulez’s music has been strangely absent from Symphony programming, even under the Directorship of his compatriot and mentee, so the showcasing of this formidable 40-minute piece felt particularly momentous.

Like most of Boulez’s music from the 1970s onward, sur Incises includes several passages that feature a steady beat and rapidly repeated notes. A good example is the Messiaenesque gamelan heard halfway through the first of its two “moments”, which coupled with the work’s unique instrumentation (three trios of piano, harp and mallet-centric percussion) gives the impression of a post-serial Reich (though Robin Maconie claims Stockhausen’s Mantra as a precedent). Another remarkable passage is the Nancarrow-like tutti about five minutes before the end. At other times, dazzling flurries are juxtaposed with calmer passages (the above links are to Boulez’s own performance with Ensemble intercontemporain, available in the 13-CD Deutsche Grammophon set of his complete works, which I review here).

The dominant motive in the piece, though, is a short-long rhythmic gesture akin to what drummers call a flam. It’s audible in the first piano right at the beginning, and recurs throughout the work, often with the short note in a different instrument than the subsequent clang. To pull off such highly coordinated music, the performers must not only know their parts cold, but must also coalesce into an incredibly tight ensemble. Only then does the ultimate interpretive goal become attainable: articulating the composite lines that traverse the three trios, and emphasizing the multilevel climaxes, anticipations and resolutions that drive this unceasingly complex music forward. As guest pianist Jacob Greenberg put it, “every phrase in the piece has a goal”. Not only was the band up to the task, but, in contrast with the introverted, austere sound world of Schnee, whose October performance benefitted from a measure of Dausgaardian reticence, tonight’s sur Incises profited from Morlot’s ever-present exuberance. Wouldn’t a future guest engagement with him conducting Rituel (in memoriam Bruno Maderna) be a treat?

The stereotype of Boulez as the ultimate cerebral composer is belied by his extraordinary command of instrumental color, something that always gave his music an edge over the legions of academic composers with a similar bent. Morlot and company’s rendering of this score reinforced Boulez’s proper place within the long line of French composers—from Berlioz, Debussy, Ravel and Messiaen onward to the spectralists—who have been infatuated with color and organic, self-generating form.

As a concluding round of hoots and applause died down, one could observe more than a few lumpy throats and damp eyes among the assembled Seattleites who left Benaroya Hall contemplating the departure of an exceptionally charismatic and personable conductor who has succeeded beyond all expectations at winning the hearts and minds of the city.