Tuesday, September 19, 2017 saw the first concert of the season at Monk Space, and for this occasion Luciano Berio’s challenging Sequenza series of virtuoso pieces were performed by the top musicians in Los Angeles. The event was also a fund-raiser to support new music at Monk Space with the musicians generously donating their time and talents for this extraordinary concert. A full crowd wedged itself into the cozy spaces of the Koreatown venue to hear, as the poet Edoardo Sanguineti wrote “…the sequence of sequences, which is the music of musics according to Luciano.”

Tuesday, September 19, 2017 saw the first concert of the season at Monk Space, and for this occasion Luciano Berio’s challenging Sequenza series of virtuoso pieces were performed by the top musicians in Los Angeles. The event was also a fund-raiser to support new music at Monk Space with the musicians generously donating their time and talents for this extraordinary concert. A full crowd wedged itself into the cozy spaces of the Koreatown venue to hear, as the poet Edoardo Sanguineti wrote “…the sequence of sequences, which is the music of musics according to Luciano.”

Each Sequenza is written for a different instrument and performed solo by a different musician, so to allow for set changes and the length of the program, the concert was held simultaneously in two spaces – the normal Monk Space warehouse and a smaller annex. It was impossible to hear all of the pieces, but everything was timed to allow those in the audience to move between the spaces and hear several different the pieces, even if they were not in the same place. The audience was politely careful to avoid entering or exiting during a performance and so this arrangement worked fairly well. I chose to stay in the warehouse for the first half of the concert and move to the annex after the intermission.

Before each Sequenza a few short lines from a Sanguineti poem were recited by Kirsten Ashley Weist. The first piece heard in the warehouse was Sequenza IV – Piano (1965), performed by Mari Kawamura and this began with a number of short, sharp chords followed by a series of complex phrases. There was no regular beat to follow but rather a chain of intricate and technically demanding passages, sometimes mixed with longer, sustained chords. There is a generally unsettled feeling to this music that often combined with the mysterious and uncertain. The intensity seemed to increase as the piece progressed, but the anxiety was occasionally relieved as the rapid phrases were allowed to ring out and decay into brief silences. Ms. Kawamura was duly focused and her technique proved equal to the difficulties of the score. Sequenza IV, with all its convolutions and complexities is anxious and disquieting music, but this was masterfully realized by Ms. Kawamura’s precisely passionate playing.

Sequenza XIVa (2002) for cello followed, while another version for bass was performed by Tom Peters as part of the program running in the annex. After the introductory lines of poetry, cellist Ashley Walters began Sequenza XIVa with soft drumming on the cello body and some lively pizzicato notes on the open strings. This made for an intriguing combination and it seemed as if there were two players on the stage. Strong arco passages soon followed, producing a somewhat somber feel but rapid strumming on the strings plus a series of rising and falling trills restored the complex character of this piece. Incredible sounds poured from the stage in a series of extended techniques that were variously angry and active, quiet and timid or occasionally warm and smooth. The texture constantly swirled and shifted, never settling for long. Ms. Walters was, however, in complete command of her instrument, extracting all of the colors – and then some – from the cello palette.

Sequenza VII – Oboe (1969) was next, performed by Paul Sherman. This began with a clean electronic drone issuing from a speaker on stage. The oboe entered matching this, then varying in pitch slightly so that the interactions between the two tones was clearly heard. The electronic drone approximated the timbre of the oboe, but remained continuous and never changed in pitch. Rapid scales and runs from the oboe followed, crossing through and weaving around the drone, and this worked into a kind of conversation between the two. The passages became increasingly complex – intense but always controlled – and brought to mind Coltrane in his final years. The playing of Paul Sherman was nimble yet precise and the close acoustics of the warehouse helpful in amplifying every detail. Sequenza VII is a formidable piece for the oboe and this performance elicited cheering and strong applause.

Sequenza X – Trumpet (1984) followed, performed by Dan Flores. This piece calls for the trumpet sounds to be directed at the piano strings occasionally for resonance, and Rafael Liebich was seated at the keyboard to oversee the sustain pedal. The trumpet began by issuing a series of strong single notes, followed by trills and rapid, spiky phrases. From time to time Flores turned to his right, aiming the bell of the horn towards the open piano. The piano strings resonated with the trumpet notes, ringing out into the audience with a sort of ghostly echo. The close confines and lively acoustics of the warehouse enhanced this effect which was all the clearer given the powerful playing by Mr. Flores. Sequenza X is just as complex as any of the pieces, as Flores described in the program notes: “As you can hear throughout the different sequenze, Berio offered both a consistent set of textures and effects he wanted created, ranging from trilled notes on one pitch, frantic scale runs, and extreme dynamic contrasts, to more instrument native ideas.” Although intense and energetic, Flores filled this piece with a strength and confidence that was never aggressive or intimidating. Sequenza X was performed with prodigious stamina and exemplary consistency – the intonation and tone were as strong at the finish as they had been at the beginning – a difficult piece played with vigor and grace.

After the intermission, three more sequenze were performed in the annex, a smaller space off the main entrance. This was about one third the size of main warehouse space and so even more intimate. Jason Barabba introduced Sequenza V – Trombone (1966) with a few lines of poetry by Sanguineti, and Matt Barbier took the stage to begin. A sharp note was sounded from the muted trombone followed by a series dramatic wah-wah effects along with some mysterious vocal sounds between breaths. Barbier’s playing was strong and confident, even when the passages became rapidly animated and technically challenging. All of this was done without any score in view, Barbier having studied this piece as a student as he explained in the program notes: “…the piece does have a very nostalgic place for me as when I started to learn it I ended up having about ten days to do so for a master class with Mike Svoboda. That moment laid the foundation for our relationship and Mike has been an incredibly helpful resource as I’ve found my own creative path.” As the piece progressed, the sounds coming from the trombone increased in variety, including growls, something resembling a motor boat and booming phrases followed by brief silences. Barbier’s playing was powerful but controlled, and he produced an astonishing array of effects from the trombone with casual ease.

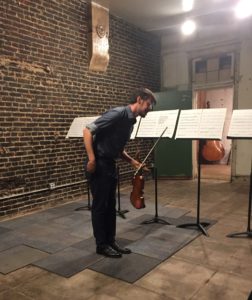

The final two sequenze in the annex program followed. The first of these was Sequenza VIII – Violin (1976), performed by Andrew McIntosh and for this no fewer than five music stands were lined up together, each holding a page of the score. Sharp, plaintively anxious chords began this, followed by more and increasingly complex phrases. The sounds became more animated as the piece progressed, but this did not disturb the composure and poise of McIntosh as he methodically worked his way down the row of music stands. Many different dynamics and textures came and went; some phrases were full of small, quietly detailed notes, others realized with broadly strong chords – and everything in between. All of this unfolded with the careful attention to detail so characteristic of McIntosh’s playing and the audience responded with extended applause.

The final two sequenze in the annex program followed. The first of these was Sequenza VIII – Violin (1976), performed by Andrew McIntosh and for this no fewer than five music stands were lined up together, each holding a page of the score. Sharp, plaintively anxious chords began this, followed by more and increasingly complex phrases. The sounds became more animated as the piece progressed, but this did not disturb the composure and poise of McIntosh as he methodically worked his way down the row of music stands. Many different dynamics and textures came and went; some phrases were full of small, quietly detailed notes, others realized with broadly strong chords – and everything in between. All of this unfolded with the careful attention to detail so characteristic of McIntosh’s playing and the audience responded with extended applause.

The final piece in the annex program was Sequenza XI – Guitar (1987) performed by Mak Grgić. This was every bit as complex as the other sequenze, but the conventional sounds of the classical guitar seemed to soften the agitation despite the many notes. Strong strumming added energy and and a sense of forward motion, and the extended techniques at times broke through the overall sense of familiarity – but this piece never felt anxious or uncomfortable. The feeling was most often warm and graceful, even through the more intense stretches. The technique by Grgić was flawless as he scrolled through the score using a foot pedal connected to an iPad placed on a music stand. Loud cheering and applause followed this exceptional performance.

Perhaps the most fascinating aspect of this concert was just how far Berio pushed the envelope for each instrument – almost, but not quite, exceeding what was possible for the virtuoso to actually play. That each of these was successfully carried out – and that Los Angeles has the personnel capable of such prodigious playing – is a credit to our local musicians. Sequenza – Sequenza! was an amazing demonstration the great artistry resident in our new music community and much credit goes to the Tuesdays@Monk Space organization for making this extraordinary concert possible.

Other players in Sequenza – Sequenza! were:

Sequenza IX – Clarinet (1980), Brian Walsh

Sequenza VI – Viola (1967), Diana Wade

Sequenza II – Harp (1963), Elizabeth Huston

Sequenza XIVb – Bass (2002, rev 2004), Tom Peters

Sequenza XII – Bassoon (1995), Jonathan Stehney

Sequenza I – Flute (1958 rev. 1992), Sara Andon

Sequenza III – Voice (1965), Stacey Fraser