Helmut Lachenmann at SpoletoUSA

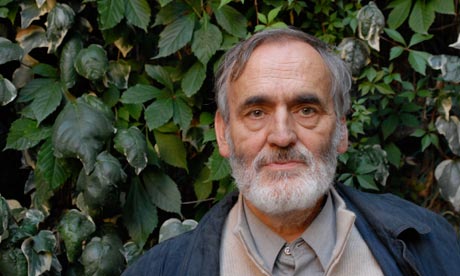

Helmut Lachemann, 80, this November, is one of the most important, original and influential living composers. To hundreds of younger composers whose ambition is to push the boundaries of music and sound beyond its presumed limits, he is a God-like figure, the reigning king of musical post-modernism. Think Stockhausen or Cage, tripled down. Extreme, thrilling, unexpected, visionary, painful, edgy. If he were a Zen master, his mantra would be “Who knows the sound of a beetle lying on its back?”

Helmut Lachemann, 80, this November, is one of the most important, original and influential living composers. To hundreds of younger composers whose ambition is to push the boundaries of music and sound beyond its presumed limits, he is a God-like figure, the reigning king of musical post-modernism. Think Stockhausen or Cage, tripled down. Extreme, thrilling, unexpected, visionary, painful, edgy. If he were a Zen master, his mantra would be “Who knows the sound of a beetle lying on its back?”

For listeners who prefer their “classical” music with a touch of consonance, he is one of those composers whose work is more fun to talk about than to actually listen to.

All of which makes John Kennedy, director of contemporary music for SpoletoUSA, a brave man, indeed, for making the American premiere of Lachemann’s opera Das Mädchen mit den Schwefelhölzern (The Little Match Girl) the centerpiece of this year’s Spoleto Music in Time Series. Conceived on a grand scale, Lachemann’s retelling of the tragic Hans Christian Andersen tale of the little girl who measures out her final hours by striking matches for a moment of warmth on the freezing street, employs 106 musicians and various other theater performers.

Lachenmann refers to his compositions as musique concrète instrumentale, basically a musical language that embraces the entire sound-world made accessible through unconventional playing techniques. According to the composer, this is music

“in which the sound events are chosen and organized so that the manner in which they are generated is at least as important as the resultant acoustic qualities themselves. Consequently those qualities, such as timbre, volume, etc., do not produce sounds for their own sake, but describe or denote the concrete situation: listening, you hear the conditions under which a sound- or noise-action is carried out, you hear what materials and energies are involved and what resistance is encountered.”

To take a simple example, guitarists generally try to limit the sound of nails clacking on strings or accidental glissandos produced by sliding their fingers up and down the strings between chords. Their goal is play as faithfully as possible only the notated sounds. In Lachemann’s musique concrete world, these scratches, squeaks and sighs are all part of the music. Through amplification and a plethora of techniques that he has invented for wind, brass and string instruments, Lachemann creates difficult, uncompromising works that are, like their creator, wholly original. His scores place enormous demands on performers. They may be only works in the modern repertory in which players may need a shower after the piece is finished.

Coming as it does in the 40th Anniversary Year of Spoleto with all the attendant “feel good” celebrations, the programming of such a controversial composer as Lachenmann is a welcome sign that SpoletoUSA that the nation’s best—and probably most financially successful–arts festival is still not afraid to take risks and push the boundaries of original performance. Founder Gian Carlo Menotti would be proud.

To appreciate Lachemann requires listeners and performers to forget whatever inherited notions they may have about beauty in music. “Try to like it,” he often tells audiences about to hear his work for the first time. For those willing to suspend their preconceptions, his music offers great listening experiences and, yes, even a strange kind of beauty.

Lachenman will be in attendance at the Festival and will participate in a conversation between Kennedy on May 27 (including a performance of Lachenmann’s piece Got Lost); a performance of Lachenmann’s Ein Kinderspiel and Kenndy’s Spoletudes on June 4, and a performance by Stephen Drury of Lachenmann’s monumental piano solo Serynade, plus Oscar Bettison’s 2014 work for small ensemble An Automated Sunrise (for Joseph Cornell).

Have a comment? Leave it on our Facebook page. The robot spammers have taken over the comments here.