(This is an expansion of an earlier post for a concert ultimately postponed due to snowstorm Jonas in January)

(This is an expansion of an earlier post for a concert ultimately postponed due to snowstorm Jonas in January)

Augustus Arnone performs a double bill of Milton Babbitt’s solo piano works including the complete Time Series, at Spectrum, Sunday March 6, at 12-5 pm (12 and 3:30)

This year marks the centenary of the legendary composer Milton Babbitt (1916-2011). To my ears, his extensive body of piano works especially channels his singular charm as a raconteur. Over the decades a number of pianists have championed some of his major piano works, for instance Robert Helps and Robert Miller performing and recording his Partitions (1957) and Post-Partitions (1966) in early days and much more recently Marilyn Nonken did as much with Allegro Penseroso (1999). Babbitt’s Reflections for piano and synthesized tape (1975) has been performed by the likes of Anthony de Mare, Martin Goldray, Aleck Karis, and Robert Taub, the latter two of whom also recorded it. Robert Taub and Martin Goldray recorded and released full-length CDs. Alan Feinberg too presented stellar renditions of Minute Waltz (1977), Partitions (1957), It Takes Twelve to Tango (1984), Playing for Time (1979), and About Time (1982) on a 1988 CRI CD.

Yet only one pianist has earned the distinction of presenting the entire oeuvre of Babbitt’s solo piano works in concert. And that is Augustus Arnone, who performed the entire set, spread over two concerts, in 2008. In honor of the Babbitt centenary, Arnone is performing the entire set again (this time spread over three concerts) at Spectrum on Ludlow in NYC. Due to a postponement caused by storm Jonas in January, Arnone is performing the second and third concerts in one afternoon this weekend!

Yet only one pianist has earned the distinction of presenting the entire oeuvre of Babbitt’s solo piano works in concert. And that is Augustus Arnone, who performed the entire set, spread over two concerts, in 2008. In honor of the Babbitt centenary, Arnone is performing the entire set again (this time spread over three concerts) at Spectrum on Ludlow in NYC. Due to a postponement caused by storm Jonas in January, Arnone is performing the second and third concerts in one afternoon this weekend!

The largest work on the program is Canonical Form (1983) which I’ve heard several Babbitt aficionados recently describe as their “favorite” and “most beautiful” Babbitt composition. The most recent work is The Old Order Changeth (1998). Arnone’s performance also presents a rare opportunity to hear the entire ‘The Time Series’ (Playing For Time (1977), About Time (1982), Overtime (1987)), the last part of which has never been released on a commercial recording. This much constitutes concert II, the first half of this Sunday’s double bill, which starts at 12 noon.

In the final concert (concert III) which starts at 3:30, Arnone presents a variety of works spanning nearly all of Babbitt’s professional career, from the mid 1940s through the remainder of the 20th century and beyond. Tutte Le Corde (1994) represents Babbitt’s most streamlined and ingratiating late style, which is a nice inclusion for the final recital of the series. On this recital we’ll also be treated to some of Babbitt’s wittiest and pithiest: Minute Waltz (1977) and It Takes Twelve to Tango (1984), which are perhaps the only Babbitt works to clearly project rhythms associated with a familiar genre. It Takes Twelve to Tango leaves us unsure whether to imagine a single 12-legged Argentinian dancing spider or a communal square dance gone dodecahedral! Either way, brilliant sparks fly from these eccentric collisions of tradition and avant garde.

Babbitt’s Three Compositions for Piano (1947), the earliest work in the series, is to my ears the closest Babbitt ever came to neo-classicism, its first movement being a clean perpetuum mobile and its second movement a veiled tribute to Schoenberg’s expressive piano textures. While Duet (1956) is the closest Babbitt ever came to a lullaby, his Semi-Simple Variations, of the same year, is perhaps his jazziest jaunt on the ivories, an adventure amusingly exploited in the Bad Plus and Mark Morris Dancers’ adaptation.

Of course the series wouldn’t be complete without Babbitt’s most uncompromising trailblazing Partitions (1957) and Post-partitions (1966). Nowhere is his engenius originality more startlingly on display than in these works. In Partitions in particular, the activation and deactivation of various high, low, and middle registers of the piano guides the listener through an uncanny but navigable maze of contrapuntal intricacy.

Between the two concerts, at 2:30, will be an interview-discussion between me and Indiana University composer-theorist Andrew Mead, a former student of Babbitt’s at Princeton and author of the acclaimed book An Introduction to the Music of Milton Babbitt (1994, Princeton University Press) and many articles. This will also be an opportunity for questions from the audience. Whether you’ve been merely curious about Milton Babbitt’s music and legacy, or are already a long-time follower, this is an opportunity to spend part of the afternoon in the good company of Babbitt’s music and its admirers.

Augustus Arnone: The Complete Piano Works Of Milton Babbitt, Concerts II & III

Sunday March 6, concert II at 12 pm; pre-concert discussion at 2:30; concert III at 3:30.

$20, $15 (Students/Seniors) for each concert or $30/20 for both concerts.

Spectrum, 121 Ludlow St, NYC.

More info: http://www.facebook.com/events/185521401798997/

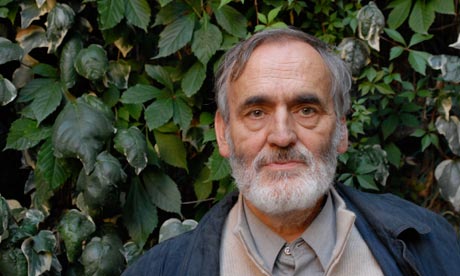

Helmut Lachemann, 80, this November, is one of the most important, original and influential living composers. To hundreds of younger composers whose ambition is to push the boundaries of music and sound beyond its presumed limits, he is a God-like figure, the reigning king of musical post-modernism. Think Stockhausen or Cage, tripled down. Extreme, thrilling, unexpected, visionary, painful, edgy. If he were a Zen master, his mantra would be “Who knows the sound of a beetle lying on its back?”

Helmut Lachemann, 80, this November, is one of the most important, original and influential living composers. To hundreds of younger composers whose ambition is to push the boundaries of music and sound beyond its presumed limits, he is a God-like figure, the reigning king of musical post-modernism. Think Stockhausen or Cage, tripled down. Extreme, thrilling, unexpected, visionary, painful, edgy. If he were a Zen master, his mantra would be “Who knows the sound of a beetle lying on its back?”