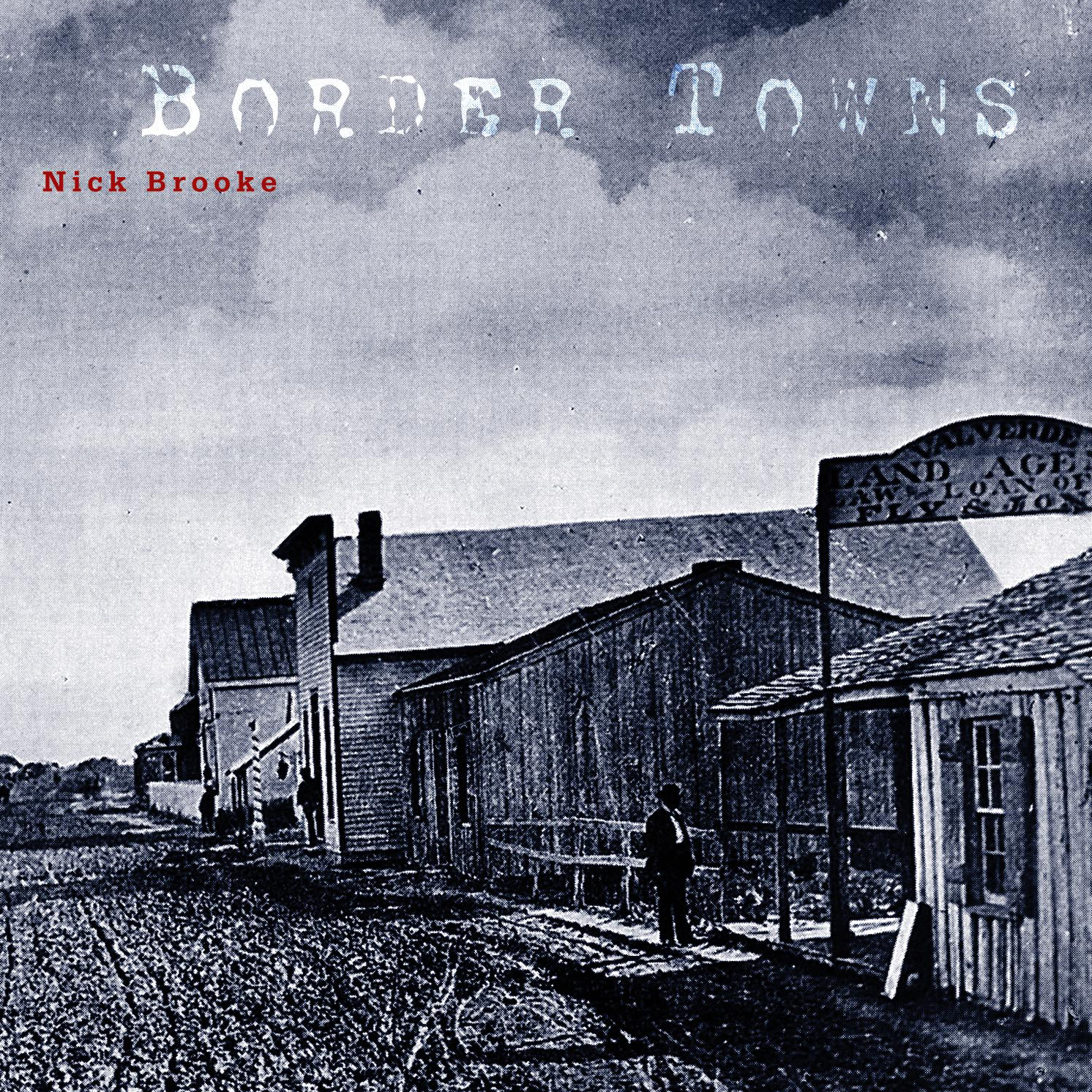

Nick Brooke: Border Towns

To experience Border Towns is to undo the idea of both. The border is metaphorically ubiquitous—as powerful as it is arbitrary. Towns are more immediate—tactile and moving to the pulse of indeterminate social interaction. Together the words form not an oxymoron but a median. Such is the spirit that moves composer Nick Brooke in this quasi-opera of Americana and stardust.

The music’s formula is diaristic, appropriating snippets from songbooks familiar and not so familiar, gunpowder from the popular canon loaded into a rather different cannon and shot across the past century until fleetingly recognizable. Brooke’s intertextual approach lays new coordinates over cartographic mainstays, in which resound the piece’s seven embodied singers—voices treading bullion in a cold electronic stew.

Movements like “Silver City” tickle the synapses of our collective memory, opening in a Judy Garland nightmare with the barest intimations of rainbows. An old radio pays homage to underlying frequencies, flagging the limits of nostalgia in what little we may recognize. What begin as utterly ingrained snippets become new beginnings, radiant and free. The end effect is haunting in the best way possible.

Subsequent movements chew their respective morsels of philosophic disturbance. Whether the overt sampling aesthetic of “Del Rio” (a deft reconstruction of a ubiquitous sound byte) or the distant mountain spirit of “Heart Butte” (a pretty mélange of rodeo, Roy Orbison, and Dolly Parton balladry), an oddly compelling backstory emerges by virtue of Brooke’s narrative integrity. The grander arc takes shape in a chain of referential vertebrae, disks filled with everything from Whitney Houston to Steve Reich. Other portions glisten with cinematic qualities. In the latter vein, “Jackman” smacks of thunder with its battle cry, its implications of outer space as dense as its decays are short. “Tombstone” is another. Dotted by splashes of Chinese gongs as it rides the tailwinds of stray bullets and Hollywood stereotypes, it traverses landscapes of lock-grooves and shattered DJ remnants. Border Towns recycles even itself, beginning and ending somewhere not over the rainbow, but in a place without space, folded like a paper football and flicked into its own gaping mouth.

Interspersed throughout this exercise in anthemic surgery are various ambient reflections: train whistles, cross lights, pedestrian babble, sound checks, impassioned listeners, crickets, church services, and the like fill the interstices with quotidian fascination. From their manipulations of source text and flame emerges a quilt of hymnody, torn and re-squared until it burns.

The clock ticks only for those who hear it.

~Interview with Nick Brooke~

1. What is your background as a composer and as a listener?

I was classically trained at Oberlin, though in a healthily offbeat way, and grad studies at Princeton happily did nothing dissuade me from mixing anachronistic materials in my current polyglot manner.

I do listen voraciously cross-genre, coming from a deep interest in getting to know people, contexts, and cultures. I tend not to listen to recordings much—solo listening can feel solipsistic and lonely. I prefer live performance. And given experiments with theater and dance over the last decade, I’m much more comfortable in those mediums than I used to be.

2. Talk a little bit about the history of Border Towns: in terms of both its evolution as a piece and the slices of Americana that make their way into the mix.

When I started Border Towns, I saw a lot of theater and musical groups going on these “all-gone-to-look-for-America” trips and it all felt wrong, so wrong. The whole genre of musical Americana is often engaged in portraying and skewing one side of a multiplicity that’s indescribable. Americana often thumbtacks culture to the wall rather than asking questions about it. So I wanted to use Border Towns to unpack musical icons, but also engaging somehow with those de Toqueville-like-trips—literally traveling around the country.

3. Is there an inherent visual or theatrical element in Border Towns? The music almost screams for it.

Completely. Most of the music is created with the choreography already in mind, often in canon or some kind of physical and musical structure. “Tombstone” is literally a calf-roping contest between two people, as well as a fugue between Patsy Montana and Gene Autry. In “Ocean Grove,” people are laid on blankets, while rapturously singing Ray Charles (“I see”). Then, through a laying on of hands, these performers are converted into Bruce Springsteen (“Born! Born!”). It’s a canon in seven parts, the number of singers in the piece. I need to predict the exact number of physical events when I compose the music, and the choreography develops in lockstep with the samples. (There’s a primer on this weird process on my website.)

4. The first word that came to mind when I listened to the album was “plunderphonics,” although your aesthetic seems like a more organic or live iteration of John Oswald’s mission of audio piracy. In this respect, I am inclined to align it more with the live mash-ups of a group like Ground Zero, whose Revolutionary Pekinese Opera seems the closest analogue. How would you situate Border Towns in terms of genre or musical space?

I enjoy Oswald and Ground Zero, though in terms of mash-ups I tend to take the slow route, with lots of silences, and I often attempt to completely break down then reassemble a specific genre, or even just a song. Plunderphonics and Revolutionary Pekinese Opera have a joyous aesthetics of excess to me, and also revel in effects like tape delay and studio layering. I tend to go for a more “real” sound, which ends up being surreal when you perform it live. A performer sings x song, but the words and phrases are in completely different places, and it still somehow makes sense; at the same time, it plays with memory and meaning. Because I’m using live performers, using the sounds of early tape manipulation or even electronica breaks a surreal plausibility I’m trying to establish. And in Border Towns, the materials are often dealt with more procedurally than these other composers: i.e., “Heart Butte,” which tries to deal in a semi-exhaustive way with slow, classic country.

5. An especially delightful aspect of Border Towns is the way in which it flirts with our nostalgia. Familiar songs are quickly swapped out for others, such that by the end we experience a new folk narrative. Is your intention with the piece to do simply that, or does it have broader, extra-musical aspirations as well?

In making each song, I often tried to go against the grain of the nostalgia, or at least create a new meaning to each song or genre. And of course if I could exactly pinpoint that meaning here, I’d be preaching, and it would become clichéd. The ideas for Border Towns emerged at a time when the “Lomax remix” genre, such as Moby’s Play, was at its height. I resisted the comfortable, warm electronic remix broth given to these samples. Did people realize the issues of Paul Robeson singing “still longing for the old plantation”, or why “cowboy music”—a genre of guys often falsetto yodeling, was anachronous? I was trying to unpack assumptions on a structural level, by the choices of what I remixed and where. I wanted to be omnivorous, and substitute old traditions, even stereotypes, with something else. Each piece take on a different icon—Tex-Mex, border radio, plantation songs, cowboy music—but tries to bend them at moments of expectation.

6. The vocal performances on Border Towns are wonderful. How did you settle on these particular musicians and how did the recording project all come together?

It’s always a challenge. Together with Jenny Rohn, my co-director for the live performances, we’re always looking for that experimental “triple threat”: people who sing, act, move, and also understand the weird, tricky-to-sing music. Some of these singers are uncanny chameleons. Some are hugely gifted in physical theater. It came together as a performance at HERE’s Resident Artist Series first—then I took it to the studio.

7. How do the ambient interludes function in Border Towns?

In a way, the ambient “interludes” are islands of realness. The sounds are actually taken from trips to the border towns on which each song is purportedly “based.” But, outside of these ambient interludes, the songs take on stereotypes of Americana, mass-produced materials that I often found sold, broadcast, or otherwise referenced in the places I visited. Cage once said if you destroy all recordings people will learn to sing again. Likewise, if one stops asking the potentially obsolete question, “What do people from this place listen to?” you just end up listening, and that’s the best part. In recording ambient sounds, I’m vamping off the long tradition of acoustic ecology and soundscape composition. In the final song of Border Towns, the ambient recordings swallow up a single performer on stage, maybe in a final moment of immersive, real listening.