The Art of Hearing

The pseudo-fact that we are ‘visual creatures’ has been drummed into mass culture for the past several decades. It’s pernicious pieces of propaganda, one of those marketing tools that is so pervasive and in-plain-sight that social critics and paranoids searching for subliminal messages and methods of mass coercion not only overlook it, they embrace it. We see and therefore we buy what we see is the way it goes, from artful design to pornography to fine art, where currently overcompensated rentiers pay immoral sums for works meant that, when hung on the wall of the McMansion, are meant to dazzle and intimidate with their pedigree and cost.

It’s bullshit, of course. Yes we see and are interested in what we see, but our most important sense organ is our ears, we are hearing creatures. Our eyes are promiscuous and fickle, what pleases them changes from year to year and culture to culture. But our ears are connected to our lizard brains and our souls. The thing that goes bump in the night is universal and eternal, the way it sets our hearts racing and sense on edge is as human as it gets, and the effect that sound has on us is exponentially more powerful than that of images. As R. Murray Schafer has pointed out, we can’t close our ears.

But it’s only recently in human culture that we have been able to share sounds beyond the immediate range of our voices and instruments, and to preserve them beyond the end of their decay. It took 30,000 years to get to the technology that we’ve had for not even 150. Unlike painting, sound recordings became a consumer market almost immediately, and the mass reproduction of sound has also been inherent to its commodification, so intrinsic that it’s never been remarkable, while Pop Art was revolutionary. All art markets aspire to the condition of music …

After infrequent, fragmentary fits and starts, the Museum of Modern Art, the premiere meeting place of the fine arts and the market, has ventured into the dimension of the ear with Soundings: A Contemporary Score, their first curated show of sound art. You could encounter works that use sound in previous visits, pieces from Bruce Naumann and John Baldessari and most notably Janet Cardiff’s extraordinary Forty Part Motet but there was never any attempt at focus and organization. Now there is, but lack of focus, organization, real curation is a crippling flaw in the exhibit.

The problem is that curator Barbara London and Museum Director Glenn Lowry can’t hear. They’re not deaf, they just don’t appear to listen, or else they chose to believe their lying eyes, because Soundings is heavy on the visual and shallow and narrow on the audible, with some important exceptions. The show is put together with a visual and narrative sense, the emphasis is on objects and the explanations of same, and so misses the point entirely. Sound is not an object, it is a sensation, literally a vibration, something that exists while it is in motion in time, then dissipates.

It’s also something that is a universal constant, there is even sound in space. While art is something we make, sound exists independent of human beings. The sound art/installations that have the greatest effect are the ones that are the simplest, that discover sound and channel it in our direction, rather than manufacture or manipulate it. There are pieces in the show that are vapid, bad, and even worse. Overdetermination is a general problem. Richard Garet builds a device that fussily amplifies the sound of a marble rolling on a turntable; Haroon Mirza frames Mondrian’s Composition in Yellow, Blue and White and accompanies it with some arbitrary and awful chiptune house music; Susan Philipz eviscerates Pavel Haas’ Study for Strings, an unbelievably heroic and mind-bendingly morally complex composition from Theresienstadt, destroying the musical content in service of what is essentially propaganda for her own supposedly historically informed sensitivities. It’s repugnant.

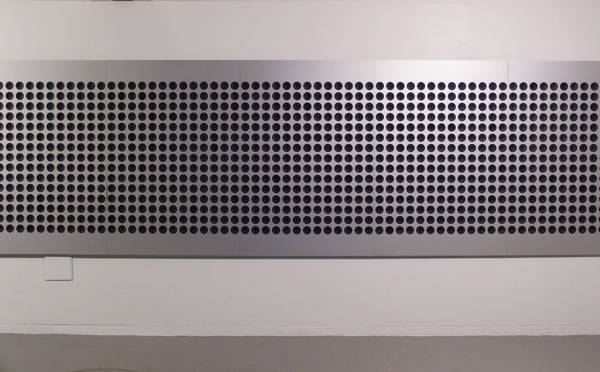

There are some mediocre, mildly interesting works on paper that refer to sound, but they make no sound. Carsten Nicolai’s visualization of infrasound is pleasant, Jana Winderen’s transformation of ultrasound into frequencies we can hear is unsurprising but lovely. The strongest works are very strong. Sit on Sergei Tcherepnin’s subway bench and the magnets he built into it make it moan and shudder. Walk past Tristan Perich’s Microtonal Wall and the array of 1500 1-bit speakers envelops you with individual sounds that, when taken together, create a Doppler effect as well as pulsating difference tones and a sweep of pitch from high to low: music. Jacob Kirkegaard and Stephen Vitiello both make sound out of space and put it into the museum. The latter has an installation in the garden that plays the sounds of different bells in the New York area every minute of the hour. Along with the beauty, there is a satisfying sense of the history of the sound of the bell which marked time for centuries before it became a feature of music. And the former placed microphones and cameras in buildings in Chernobyl, where there are no more human sounds, and captured the changing frequencies of the rooms as they warmed during the day. It’s tremendous, rich in sensation and uncanny in the sense that he has captured what the remnants of civilization will sound like when we are no longer on the earth.

I applaud London’s intentions, but the show is wrong, made out of ignorance. The collection of films prominently features the idiotic shallowness of Luke Fowler, with some unremarkable shorts and a Nick Cave video. I don’t understand how that came about. MoMA has a substantial film collection, and they must have Monsieur Hulot’s Holiday and Stalker available, just two examples of movies that use sound – not music – as an integral part of the storytelling. And nothing overcomes the inherent problem with curating sound in a museum. The gallery walls and floors are highly reflective and the ambient sound easily spikes over 80 decibels. The space is cramped and there’s little appreciation that sound art only unfolds through time, it’s not a matter of strolling through a gallery and looking at pictures for as long as you wish, you have to stop and let the sound play out. The best pieces understand this, but most of the works, the curator and the museum do not.

http://youtu.be/_92Cm8gl7Ls