The 100th anniversary of the birth of John Cage was celebrated in Pasadena, California at the Boston Court Performing Arts Center with a concert by Gloria Cheng titled Two Sides of Cage’s Coin. The Boston Court venue is comfortably cozy and all but a few of the 100 seats were filled to hear Water Music and the entire sequence of Sonatas and Interludes. Despite the modern industrial construction of the hall – it has corrugated steel walls – and a play going on in the adjacent theater, the acoustics proved more than adequate for the intimate space.

The 100th anniversary of the birth of John Cage was celebrated in Pasadena, California at the Boston Court Performing Arts Center with a concert by Gloria Cheng titled Two Sides of Cage’s Coin. The Boston Court venue is comfortably cozy and all but a few of the 100 seats were filled to hear Water Music and the entire sequence of Sonatas and Interludes. Despite the modern industrial construction of the hall – it has corrugated steel walls – and a play going on in the adjacent theater, the acoustics proved more than adequate for the intimate space.

John Cage was born in Los Angeles and has many connections here despite being known primarily as a New York composer. Cage studied with Schoenberg at UCLA – where Gloria Cheng is now a faculty member. He lived for a time in Pacific Palisades and later in Hollywood. Cage was also a colleague of Lou Harrison and taught at Mills College in the Bay area. To mark the centennial here in Los Angeles of the birth of John Cage – one of Americas most influential composers – is entirely fitting and appropriate.

The first piece on the program is known generically as Water Music but as Ms. Cheng explained the official title should be Boston Court, Pasadena August 24, 2012 because Cage had intended the title to be taken from wherever it was performed. This piece was first presented as 66 W. 12 at Woodstock, NY August 29, 1952 and so the title is updated on each playing. Water Music is partly music and partly performance – the score calls for a table radio, three kinds of whistles, cups and pitchers of water, a wooden stick and a deck of playing cards, all in addition to the piano. (A similar piece – Water Walk – was once performed by Cage himself on the old I’ve Got A Secret TV program and you can see this here on You Tube.)

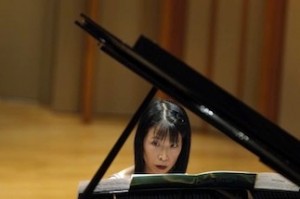

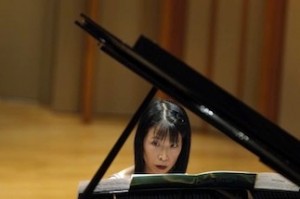

Boston Court, Pasadena August 24, 2012 started with the rolling out of a small cart full of items to center stage – the radio plays – and Ms. Cheng began a series of activities such as pouring water from cup to pitcher, blowing various whistles, etc. This was all done by timing the sequence of actions with her iPhone (a nice 21st century touch) and following Cage’s score, which was projected overhead for all to see. No one brings as much dignity to the concert stage as Gloria Cheng, but she could have been a 1950s housewife scurrying about attending to various domestic chores. When the score called for a chord or two on the piano, however, everything changes: it is the virtuoso who – with just a few notes struck – suddenly and decisively shifts the focus to an artistic perspective. It is this overlap between the mundane and the suddenly artistic that makes this piece so intriguing – our ordinary lives are never quite removed from the arts – and art bleeds into our everyday experience.

Sonatas and Interludes for Prepared Piano was written over two years,1946 to 1948, at a time when John Cage was working with choreographer Merce Cunningham. Ms. Cheng explained that because there was no room in the dance studio for drums, Cage hit upon the idea of adding various pieces of hardware to the piano strings to give it a more percussive sound. He eventually devised explicit instructions on how the piano was to be prepared and he specifies individual types of screws, bolts and plastic pieces for each of 45 different notes on the piano. A complete chart by Cage showing how the piano is to be prepared was included in the program.

To those who have never heard a prepared piano the resulting sound invariably exceeds prior expectations. The lower prepared notes have a wonderful gong-like quality while the middle register can produce beautiful bell tones. The higher notes tend most toward the percussive, at times resembling the notes from a music box. The added texture of the prepared piano is fully explored in Sonatas and Interludes which are, by turns playful, dramatic, solemn, agitated, languid, mysterious and tranquil. The ‘Sonatas’ are played in groups of four followed an ‘Interlude’ for a total of 20 pieces – all played sequentially. This work was written at a time when Cage was studying South Asian music and culture – the various pieces in Sonatas and Interludes evoke a definite exotic and mystical feeling and are intended to portray the eight permanent human emotions as defined by Indian philosophy.

As might be expected, Sonatas and Interludes is a very challenging work for the performer – from the 3 hours of piano preparation time to understanding just how each note will feel and react. And of course you can see that the piece is technically difficult just by looking at the notes on the score – rapid runs of complex arpeggios, soft quiet stretches and dramatically loud passages. Because the hardware tends to shorten the duration of the sound when a prepared note is struck, this music is typically a sequence of single notes and rapid runs with very few long chords – a good test of the performer’s dexterity. Ms. Cheng was up to all of this but what impresses most is her ability to find just the right dynamic and “touch” for each section – even with 45 of the keys prepared. I asked her afterwords if she had much chance to practice on a prepared piano and she responded that at one time she did so but now feels confident given her experience with Cage’s music. In any event the results were well-received by the audience who brought Ms. Cheng back for two curtain calls amid much cheering. Gloria then invited those interested to come on stage to look inside the piano – and help her “de-prepare” it – a gracious gesture from an accomplished performer.

This concert was sponsored by Piano Spheres and information on their upcoming concert season can be found here.