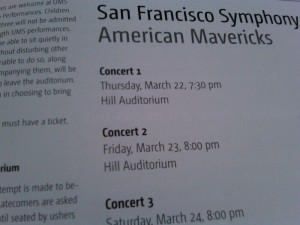

Wrapping Up “American Mavericks”

By now, the members of the San Francisco Symphony, their director Michael Tilson Thomas, and the rest of the musicians responsible for the orchestra’s magnificent “American Mavericks” Festival have left Ann Arbor for New York and the next stop on their tour: Carnegie Hall. In immediate relection, I’m confident the concerts lived up to the title bestowed upon it by Alex Ross: “the major musical event of the winter/spring season” – though, in Ann Arbor, I argue the “Mavericks” share that spotlight with January’s presentation of Einstein On The Beach.

By now, the members of the San Francisco Symphony, their director Michael Tilson Thomas, and the rest of the musicians responsible for the orchestra’s magnificent “American Mavericks” Festival have left Ann Arbor for New York and the next stop on their tour: Carnegie Hall. In immediate relection, I’m confident the concerts lived up to the title bestowed upon it by Alex Ross: “the major musical event of the winter/spring season” – though, in Ann Arbor, I argue the “Mavericks” share that spotlight with January’s presentation of Einstein On The Beach.

Immeasurable credit is due the Symphony and MTT for the sheer audacity of their programming and the high level of their performances. The music they shared with us energized Ann Arbor’s concertgoers to a level I’d never before witnessed, and I believe all those who attended feel indebted to the University Musical Society for bringing this once-in-a-generation event to our Midwestern haven.

In the mold of the 17 American composers featured on the tour, the Symphony’s four concerts were blisteringly unapologetic and daring – almost to a fault, in fact. Personally, the composers who shined the most in my ears were (in alphabetical order) Mason Bates, Henry Cowell, Lukas Foss, Meredith Monk and Carl Ruggles, but there was lots of music to go around for every concertgoer’s taste. I was heretofore uninitiated to the work of these last three composers, and, thanks to their pieces Echoi, Realm Variations and Sun-Treader (respectively), I am determined to listen to Mr. Foss, Ms. Monk and Mr. Ruggles’ music more regularly.

Before last week I was also rather unfamiliar with Mason Bates’ work, but my encounter with him, and his new choir/organ/electronics piece Mass Transmission, could not have been more impressive. Mr. Bates is, obviously, one of the most successful living composers in America, but this fact only makes his unfailingly down-to-earth character more endearing. He was very candid when he presented to us students, opening his chat by declaring his near indifference for being dubbed a “Maverick”, and later revealing his desire to achieve more lyricism in his music – something he excels at in Mass Transmission.

The Festival also gave me an opportunity to meet another top-flight American musician: renowned pianist Jeremy Denk. Charming, witty and articulate, Mr. Denk is as gifted a performer as he is a wordsmith, crafting two spectacular performances, and one stellar presentation to the UM Composition Department, while he was in Ann Arbor. Last Thursday night, Mr. Denk brought Henry Cowell’s Piano Concerto to life, and, yesterday afternoon, took part in performing Lukas Foss’ raucous and virtuosic Echoi – a work he sarcastically described in his master class as, “the hardest piece ever written”.

I’ve heard Mr. Denk play once before – this summer at the Aspen Music Festival where he gave a recital of Bach’s Goldberg Variations and both books of Ligeti’s Etudes. He is an unquestionable master at the keyboard, and his devil-may-care approach to programming – as evidenced both by Bach/Ligeti recital I heard and his pairing of the “Hammerklavier” and “Concord” sonatas – is harmonious to the spirit of the “Maverick” composers highlighted on this tour. Similarly, as much as Mason Bates shies away from that title, he is unequivocally breaking new ground in the world of American orchestral music. It appears that, to orchestras, Mr. Bates’ music represents and attractive entrée into the electro-acoustic genre. But, most importantly, works like Mass Transmission and Alternative Energy offer an easily reconcilable step towards greater performance flexibility and artistic open-mindedness – two attitudes I feel orchestras must adopt in order to survive in this country.

In many ways, the “American Mavericks” tour is a categorical emblem of how orchestras can more commonly celebrate the work of 20th and 21st-century American composers. As I hinted to before, most of the music the San Francisco Symphony presented was abstract and dissonant – thus, “challenging” for audiences – yet, even the most harrowing works were embraced by concertgoers with cheers and standing ovations. The memorable, and controversial, exception to this grateful approbation was the reaction to John Cage’s Song Books, performed as the first half of Friday night’s concert.

After thirty minutes of watching Jessye Norman, Meredith Monk, Joan LaBarbara, Michael Tilson Thomas and members of the San Francisco Symphony execute the work’s various ‘happenings’, most of the crowd applauded – except for one or two vociferously disappointed men who booed loudly. Their boomingly expressed chagrin surprised most of the people in the hall, but it also galvanized those who loved the performance, inciting them to holler louder and more enthusiastically – a crescendo that was matched by the dissenters.

Concertgoers’ chattering at the remaining performances, and the University Musical Society’s coverage of the festival, focused on this supposed controversy, but I think the booing distracted from the bigger issue with Song Books – it was followed by an hour-long intermission as the staging was removed and replaced with the orchestra’s stands and choirs. Much to its detriment, that concert ended up running for nearly three hours and yesterday’s chamber music performance was similarly protracted. I recognize I am nit picking because it is simply fantastic that a major orchestra like San Francisco’s would program such a bizarre work. However, its evident impracticality made Song Books seem like a quixotic programming choice. Cage’s music could have been more efficiently included with Altas Eclipticalis and, if presenting one of his more extreme works was absolutely necessary, he has, in my opinion, more captivating pieces than Song Books (Credo in US comes to mind).

Unfortunately, the Song Books intermission imbroglio was not my only hang-up with the “American Mavericks” Festival. For example, the Symphony represented Charles Ives – an undeniable “Maverick” – with the Henry Brandt orchestration of the “Concord” Sonata. This didn’t make sense to me seeing that Ives has so many wonderful orchestral works of his (Central Park in the Dark, the Robert Browning Overture, Washington’s Birthday, etc., not to mention Three Places in New England). Similarly, yesterday’s long concert of chamber music represented David Del Tredici with his early piece Syzygy, for soprano, horn soloist and ensemble. Michael Tilson Thomas explained how Mr. Del Tredici is a maverick for embracing tonality in the harshly academic 1970s, and proceeded to demonstrate Mr. Del Tredici’s bold, revolutionary style with one of his most dissonant and modernist compositions. I scratched my head.

With these caveats communicated, I want to reiterate the peerless magic of the San Francisco Symphony’s performances, the repertoire Michael Tilson Thomas championed and the symbolism thereof. At the beginning of this article, I related the orchestra’s presence in Ann Arbor to this winter’s presentation of Einstein On The Beach. I held mixed feelings about that piece much like my preceding response to the “Mavericks” tour. Yet, it is clear to me now – just as it was when Philip Glass received his standing ovation back in February – that this Festival is an event of immense cultural importance to the world of American music and, more idealistically, to America at large.

I am an American Mavericks fanboy, recorded all of the 13 programs, got all of the texts from the Mavericsk web site and recorded all of the 70 or so audio interviews. So, I have lived with and benefited from the radio project for quite some time. I like it a lot.

I’m certainly with you all the way on that one!

Well, you have to speak for yourself on that one. I don’t really perceive geographical centers of the music universe any more. On the other hand, when I see the season announcements for some of those West Coast orchestras I wish the NYPO weren’t so damned conservative.

Stanley: No question there is new music everywhere in NYC (and environs) these days, and I didn’t mean to suggest otherwise. What I was indicating is that NYC doesn’t have a lock on adventurous programming–I think we NY’ers sometimes get the idea we’re the center of the universe, and well, we are one center of the music universe, but not the only one. Will you grant me that?

Avoidance of adventurous programming is not a New York problem, it’s a New York PHILHARMONIC problem. Have a look at programming outside Avery Fischer, and you’ll find that there’s new music everywhere in NYC these days. A lot more than you’ll find in LA or San Fran, as a matter of fact.

Wonderful review, which demonstrates yet again that New York City does not have a lock on adventurous programming (far from it). I think the West Coast has a lot to teach us, and we need to start listening up.

Q2 at New York Public Radio has been having a “American Mavericks” celebration all of the moth of March.

I am a Q2 fanboy, and an American Mavericks (American Mavericks Radio project, Minnesota Public Radio, American Public Media) fanboy going back to when WNYC did the thirteen week presentation on serial Sundays at 4:PM. I recorded all of the 13 programs, I copied out all of the texts from the Mavericsk web site interviews, and Kyle Gann’s essays, I recorded all of the 70 or so audio interviews. So, I have lived with and benefited from the radio project for quite some time.

All of this to say that what Q2 has done, with MTT, Mary Rowell, Fred Sherry, Phil Kline has been, in my opinion, absolutely wonderful. I heartily recommend any one at all interested to go to the Q2 web site and search up the archives, of which there are plenty.