Blängen the Schlingen with Charlemagne Palestine

Pwyll ap Siôn is a composer and Senior Lecturer in music at Bangor University in Wales (UK). His strong interest in Minimalism (he’s written a book on Michael Nyman) led to his co-hosting of the first International Conference on Minimalist Music in 2007. He also made his way across the ocean for the second iteration of the conference, held last September in Kansas City, MO. Pwyll asked if S21 might like to print a few of his reactions and thoughts from the conference, and we said sure thing:

Pwyll ap Siôn is a composer and Senior Lecturer in music at Bangor University in Wales (UK). His strong interest in Minimalism (he’s written a book on Michael Nyman) led to his co-hosting of the first International Conference on Minimalist Music in 2007. He also made his way across the ocean for the second iteration of the conference, held last September in Kansas City, MO. Pwyll asked if S21 might like to print a few of his reactions and thoughts from the conference, and we said sure thing:

At the Second International Conference on Minimalist Music last September, hosted by the University of Missouri at Kansas City, part of the evening events led me to the Grace & Holy Trinity Cathedral to hear composer, performer and improviser Charlemagne Palestine. He is something of an enigma; when John Adams attended a rare performance in the 1980s, Palestine walked out after twenty minutes, leaving the audience baffled. Even those who have already seen him have no idea what to expect.

I enter the dim glow of the cathedral and notice two things: first, the sound of a drone — two notes, a fifth apart (a little like La Monte Young’s infamous Composition 1960 No. 7: two notes with the instruction ‘to be held for a long time’). The drone is low in dynamic but high in register, its reedy timbre adding a slight edge to the ambiance, but this is otherwise a rather inauspicious introduction. Secondly, there’s a merry gaggle of teddies and puppets neatly arranged on a table near the entrance, all of which appear to be wearing scarves or ribbons. I am told that this is de rigueur in the eccentric world of Palestine. But nothing quite prepares me for what follows.

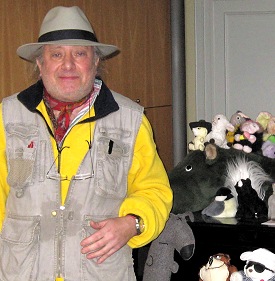

We are politely informed that the performance has already begun despite the fact that the audience is milling around, chatting casually or ambling up and down the aisles. The atmosphere is relaxed, however, and we are told that the unpredictable Palestine is (literally) in high spirits, on his second (large) glass of cognac, and has extended an invitation to members of the audience to visit the organ loft situated at the rear of the cathedral. We have to take off our shoes to do this – a complicated process since it is almost completely dark at the back of the nave – and just as we are about to be ushered by an assistant up the staircase, there is a frisson of activity from above, and the man himself appears, wine glass in hand, wearing a panama hat and dressed in bright, colourful clothes.

He strides purposefully past us towards the altar, raising his voice to speak. Rather like the drone, which continues to sound in the background, his voice is high-pitched and nasal. He announces that he will be playing Schlingen-Blängen, which has not been performed (spoken ostentatiously) ‘in the United States of America’ for decades. But he’s rambling on incoherently, maybe the cognac’s starting to take effect, and I’m starting to doubt all the hype. This increases as he proceeds to produce a ringing sound by rubbing his finger around the wine glass while emitting a series of pitches in a childlike voice.

With the performance rapidly descending into banality Palestine stops singing, abruptly turns on his heels down the aisle and back up the organ loft. Seizing the opportunity the Belgian musicologist/critic Maarten Beirens and I follow him up the stairs. Oblivious to the fact that we’re there, he is entirely absorbed in his own sound world and starts to perform.

He slightly increase the volume of the drone so that it becomes more audible, then over a period of around twenty minutes gradually applies a number of vertical wooden wedges between the keys of the organ to hold them down. Palestine opens and closes various organ stops, some slowly, some quickly, and although his actions appear arbitrary, it is evident that he is listening intently to the sound coming out, and carefully shaping it as if it were some kind of sonic plasticine. Along with these organ preparations and manipulations is his own ‘performance’ – like a rock guitarist, his legs, feet and arms dance to the drones, but this is no stage act. Even periodic drafts of cognac appear synchronous with the piece’s inexorable unfolding structure. The more I listen, the more I feel pulled in by its gravitational force, and as the volume increases and the sounds morph, I become moved – physically and emotionally – by what’s going on.

Looking down from the gallery I see the assembled teddy bears – their blank expressions suggesting that, in a strange way, they ‘hear’ too by being here – and, in the gallery area in front of us, a box of tissues lie on the floor. There’s something desperately sad about this music, a kind of search for lost innocence. Freud would probably have a field day unpacking Palestine’s psychological curiosity cabinet.

Yet with the volume increasing, existential angst gives way to an ecstatic static quality. The sound is now encompassing, all consuming, and Palestine’s focus is so complete that a dynamic force appears to impel the static drones from within. More and more keys are pressed into sustained action, and the wall of sound transmogrifies into something both magnificent and terrifying. The music is gaining inexorable momentum, yet it’s impossible to guess what will happen next. Where is he taking this? How will it all end?

Then out of the mass of sonic abstraction a strident melody in the bass register is pounded out – the rapturous closing melody from Stravinsky’s Firebird Suite – and the opening preamble with wine glass ringtone and faux-folk intoning now makes complete sense. Apparently Stravinsky loathed the organ, so its appearance amidst this seething sonic vortex is as irreverent as it is ironic.

The theme stated, and the organ now straining at the limits, Palestine applies his feet to the pedals – extracting dense semi-tonal swathes. The volume is at its peak, but more wedges are applied – almost every key is depressed – and one is being sucked into a dark sonic chasm. The organ is seriously in danger of imploding under the force of its own sonic welter and I am thinking that the performance can only end with terminal mechanical breakdown.

Then, with every sinew of the instrument strained to capacity, suddenly the light goes out in the organ loft, along with its sound – spiraling chaotically into the dark corners of the cathedral. I’m thinking that the organ has finally gone into meltdown, or maybe the church authorities have pulled the plug on Palestine’s anarchic artistry.

Then equally as suddenly the instrument powers up again, soaring up to another climactic peak before free-falling down a second time into the abyss. Surely there is nothing left to add? Powered up a third and final time, Palestine rapidly removes each wedge, one-by-one, until there remains only the fragile interval of the opening. The music stops; the silence completely deafening. The performance poised on a knife-edge.

Is this the end? Palestine takes in the last draught of cognac, moves away from the organ, and stands facing the audience. Teasing a solitary sound from the glass one last time, he projects the Firebird melody back into the church’s empty space. Solitary, fragile and final. The end of a most extraordinary musical experience.

Apologies for very confusing minor typo above. That last paragraph should read:

In our slow change works we (I think “we”, but certainly I) wanted to allow the listener’s desensitization (caused by dense complex loud sonic experience) to subside, to create music in which our auditory cognition finds no need or trigger to be fending off, simplifying down or filtering out, which would allow the ear to perceive ever finer detail, so the listening experience would be a perceptual, and emotional, process of opening up to the sound, of increasing sensitivity to music instead of the contrary.

Interesting comments. Yes there are multiple strands within what the borrowed visual arts term “minimalism”includes of music.

Back then we (or I anyway) differentiated “minimalism” from “slow change music”. The former was typically built up out of individual notes (accumulative or additive composition, e.g. Reich and Glass), and the latter tended more to be monolithic or subtractive (Radigue, some of my work, sustained tones often filtered and/or modulated, what in my own works I often though of as evolution or extrapolation processes rather than forms).

In our slow change works we (I think “we”, but certainly I) wanted to allow the listener’s desensitization (caused by dense complex loud sonic experience) to subside, to create music in which our auditory cognition finds need or trigger to be no fending off, simplifying down or filtering out, which would allow the ear to perceive ever finer detail, so the listening experience would be a perceptual, and emotional, process of opening up to the sound, of increasing sensitivity to music instead of the contrary.

Indeed. Minimalist music abounds with goal-directed motion, from the B side of Laurie Spiegel’s LP Expanding Unvierse to Terry Riley’s 1968 Purple Modal Strobe Ecstasy With the Daughters Of Destruction to Elaine Radigue’s Trilogie De la Morte to John Chowing’s computer piece Stria to LaMonte Young’s The Second Dream of the High Tension Stepdown Transformer to Julian Cope’s Odin’s Breath.

It’s goal-directed motion toward goals wholly different than those familiar in Western music twixt the Renaissance and roughly the year 1900. Minimalist music also moves from one place to another with direction and purpose — just much more slowly and far more subtly than the music of the Romantic or Classical or Baroque eras.

If you doubt this, digitize a recording of Young’s Second Dream or Radigue’s Kyema and use an audio editor to speed it up by a factor of 10. You’ll hear a great deal of movement, all purposeful.

The great discovery of the minimalists remains the revelation that acoustic smoothness and acoustic roughness exhibit a hysteresis function, ditto speeding up as opposed to slowing down the musical tempo. Because of the hardwired properties of the human ear-brain system, you can perceive meaningful musical changes when you enormously decrease acoustic roughness much more readily than when you enormously increase them. Likewise, you can readily discern meaningful musical changes when you radically down the tempo of a piece than when you radically speed it up.

The properties of the human cognitive system and the human ear/brain system place sharp limits on how fast you can play a piece of music and still recognize sensible musical structures, or experience any kind of deep emotional reaction. Ditto on how much acoustic roughness you can pile up. Beyond some fast tempo or mass of acoustically rough stacked intervals, the music tends to disintegrate into a chaotic blob ‘o stuff.

There is no obvious limit, however, to how acoustically smooth you can make the vertical structures in a piece of music and still produce audible organization and emotional impact. Even if you get to extremes of acoustical smoothness, extremely slight departures from smoothness still retain a whopping dramatic impact. Likewise, there’s no obvious limit to how slow you can play a piece and still get a coherent structure or an emotional wallop from it. One composer has produced a sound installation that only repeats every 10 years.

The problem with the statement is that it’s a bit of “yeah, so?”… Also the term “fails to” is loaded; replace with simply “don’t” and I’m great with that. But most importantly, this is only a statement about one or two specific types of minimalism. The greater category Minimalism is has all kinds of branches (most, in fact) where this description doesn’t apply at all.

Leonard Meyer described minimalist music in 1994:

Because there is little sense of goal-directed motion, [minimalist] music does not seem to move from one place to another. Within any musical segment there may be some sense of direction, but frequently the segments fail to lead to or imply one another. They simply follow one another. What say you?

A very captivating tale! Minimalism can be so hypnotic at times.

Wonderful! I love this story!