American composer Tom Myron was born November 15, 1959 in Troy, NY. His compositions have been commissioned and performed by the Kennedy Center, the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, the Portland Symphony Orchestra, the Eclipse Chamber Orchestra, the Atlantic Classical Orchestra, the Eastern Connecticut Symphony Orchestra, the Topeka Symphony, the Yale Symphony Orchestra, the Civic Orchestra of Chicago, the Bangor Symphony and the Lamont Symphony at Denver University.

He works regularly as an arranger for the New York Pops at Carnegie Hall, writing for singers Rosanne Cash, Kelli O'Hara, Maxi Priest & Phil Stacey, the Young People's Chorus of New York City, the band Le Vent du Nord & others. His film scores include Wilderness & Spirit; A Mountain Called Katahdin and the upcoming Henry David Thoreau; Surveyor of the Soul, both from Films by Huey.

Individual soloists and chamber ensembles that regularly perform Myron's work include violinists Peter Sheppard-Skaerved, Elisabeth Adkins & Kara Eubanks, violist Tsuna Sakamoto, cellist David Darling, the Portland String Quartet, the DaPonte String Quartet and the Potomac String Quartet.

Tom Myron's Violin Concerto No. 2 has been featured twice on Performance Today. Tom Myron lives in Northampton, MA. His works are published by MMB Music Inc.

FREE DOWNLOADS of music by TOM MYRON

Symphony No. 2

Violin Concerto No. 2

Viola Concerto

The Soldier's Return (String Quartet No. 2)

Katahdin (Greatest Mountain)

Contact featuring David Darling

Mille Cherubini in Coro featuring Lee Velta

This Day featuring Andy Voelker

|

|

|

|

|

Wednesday, September 14, 2005

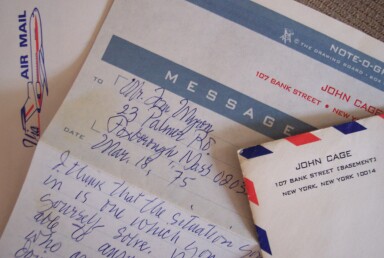

The Cage-Myron Letters

In the mid 1970s, when I was in the eighth grade, I used to go to our public library and check out stacks of LPs of electronic music. They had a great selection of Columbia-Odyssey and Folkways recordings and I just couldn't get enough of them. Everything was making sense to me (more or less) until I came to John Cage's 'Indeterminacy.' What on earth was this, I wondered. All the other electronic music I'd been listening to was so appealingly otherworldly. Now here was a guy reading stories and making it hard to concentrate on all the wonderful sounds that I was trying to hear!

But it was also clear to me that of everything I'd heard up to that point this was something different. Cage's odd but captivating voice really got under my skin. Eventually, what had been to my ear a disconcerting juxtaposition of the otherworldly and the everyday began to seem utterly magical to me. As a side benefit (and I wonder if this is true for anyone else) that album introduced me to most of the cast of characters who would occupy my thinking to varying degrees over the next 15 years.

When I found that the lovely booklet that accompanied the album raised more questions than it answered I decided I needed to write to Cage himself (c/o Folkways Records) for clarification on exactly what he was up to. What, I wanted to know, was the 'Lecture on Nothing'? Where could I get scores of his music? And could I study with him (perhaps by mail?)

Two weeks later, on a Saturday morning, my parents, both sporting looks of bemused amazement, called me down to the front door and handed me a letter from John Cage. In it Cage warmly thanked me for my interest in his work. He told me that his music was published by C.F. Peters and that they would be sending me a catalog under separate cover (the famous John Cage Document, which I have to this day.) He also suggested that I pick up a copy of his book 'Silence', as it would answer many of the questions that I had asked. He wrote that he was too busy to teach privately but that perhaps all of his work to date constituted a form of teaching. In any case I was welcome to send him my music to look at if I was so inclined.

I took him up on all of this and wrote him several more times over the following couple of years. He always answered and he was always encouraging. I was 15 and John Cage took me seriously. Needless to say it was at that point that I knew for sure I was going to be a composer, period. It didn't occur to me until years later that he probably received a lot of those letters and may have created a fair number of composers by responding to them in this way.

It eventually came to pass that I got to meet John Cage in the mid 1980s. It was at the French Embassy in Washington, DC of all places. I told him that I wanted to thank him- that when I was very young I used to write him letters, all of which he graciously and patiently answered. He was delighted and seemed genuinely fascinated. He asked my name again, what years this had been and if I could remember the address I had written to him at (I could.)

I said that I also wanted him to know that I had in fact become a composer and that while what I wrote had little if anything to do with his own orientation, I felt that everything I did I had to really earn because of what I had learned from him.

Then I told him that I had made a promise to myself that if I ever met him I would tell him a dream I'd had when I was about 14 or 15 years old. In the dream my family and I are all looking out our living room window. We are very excited because John Cage is coming to visit. Outside it is a very bright and sunny day. Even though there are green leaves on the trees, everything is covered in powdery snow, which is melting into pools of water, making dazzling reflections.

Up at the end of the street we see a huge yellow school bus round the corner. As it approaches our house we see that it appears to be empty and no one is driving. Then, sitting in the very last seat of the driverless bus, we see John Cage. He is laughing and laughing...

And there on the stage at the French Embassy is that very laugh.

posted by Tom Myron

|

| |